The Gray Market

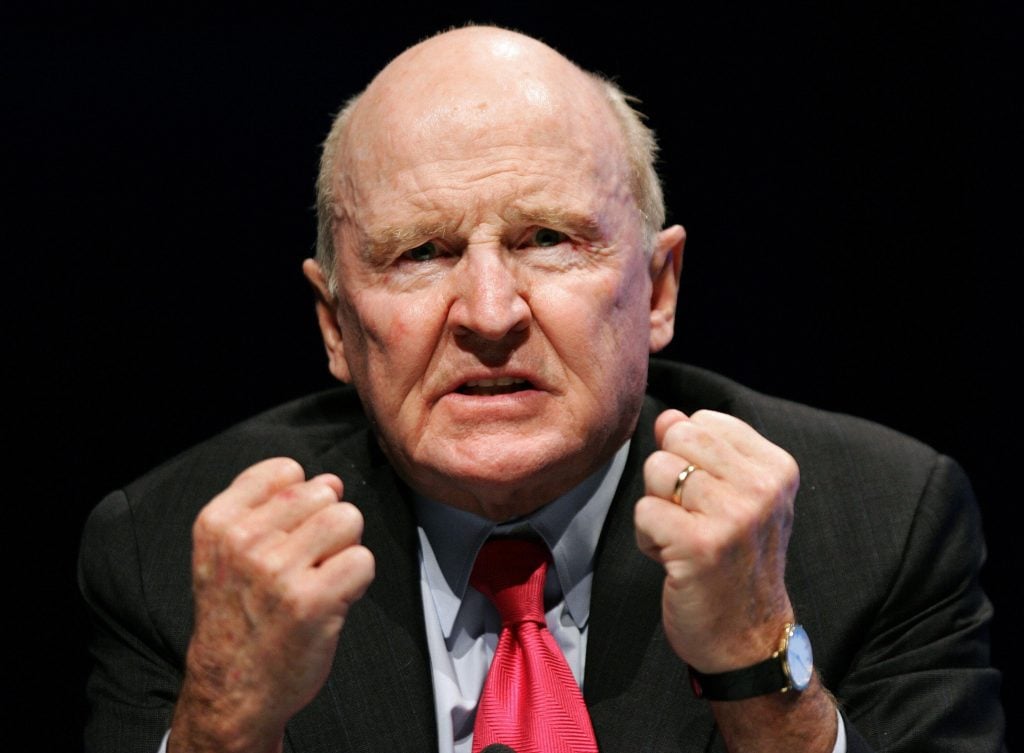

How Former G.E. CEO Jack Welch Altered the Art Market for Better and for Worse (and Other Insights)

Our columnist examines the impact of a ruthless corporate titan on the modern economy, wealth distribution, and the business of art.

Our columnist examines the impact of a ruthless corporate titan on the modern economy, wealth distribution, and the business of art.

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, redefining the term “corporate collecting”…

The art market has been shaped throughout history by unintended second-order effects from larger shifts in politics, economics, and finance. Since the 1980s, structural changes to American business have enabled the valuation of U.S. corporations and the net worth of their leadership to swell to New Gilded Age proportions. The art market has swelled right along with them to encompass tens of billions of dollars in annual sales and untold billions more in related activity. A new book has convinced me that this makes one of the art industry’s greatest patrons a man who many, if not most, of its current participants have never heard of: former G.E. chief executive Jack Welch.

Welch is the subject of The Man Who Broke Capitalism, written by longtime New York Times reporter David Gelles. Gelles previously spent several years penning a column for the Times about executive strategy that involved interviewing hundreds of top decision makers. Recently, he argued (in a standalone essay adapted from his book) that Welch “still looms over the corporate world, living rent-free in the minds of CEOs around the globe” more than 20 years after he retired.

His legacy is much more than philosophical, however. As the title of the book suggests, Gelles believes global capitalism as a whole has mutated to match Welch’s then-unprecedented experiments in inequitable compensation, cost-cutting, and the prioritization of Wall Street interests above all else. In his words…

In the decades since Mr. Welch assumed power [at G.E.], the economy at large has come to resemble his skewed priorities. Wages stagnated and jobs moved overseas. CEO pay went stratospheric and buybacks and dividends boomed. Factories closed and companies found ways to pay fewer taxes.

Welch’s ruthless gameplan became so influential because it delivered unprecedented wealth and power to his company and its shareholders for an extended stretch. According to Gelles, G.E. was worth about $14 billion when Welch took the helm in 1981; just before he retired in 2001, it was worth $600 billion, making it the largest corporation in the world at the time. No wonder Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav (who Gelles describes as “a Welch disciple”) felt justified in declaring: “What [Welch] created at G.E. became the way companies now operate.”

Much of the world is worse off for it. Gelles argues convincingly that Welch’s strategic arsenal has been disastrous for the average worker, the larger state of the global economy, and even the long-term health of the corporations who adopted his tactics. But there’s no question that the Welch method has been incredibly lucrative for a small group of winners in business and finance. By extension, it has also been manna from heaven for sellers of luxury goods, collectibles, and fine art.

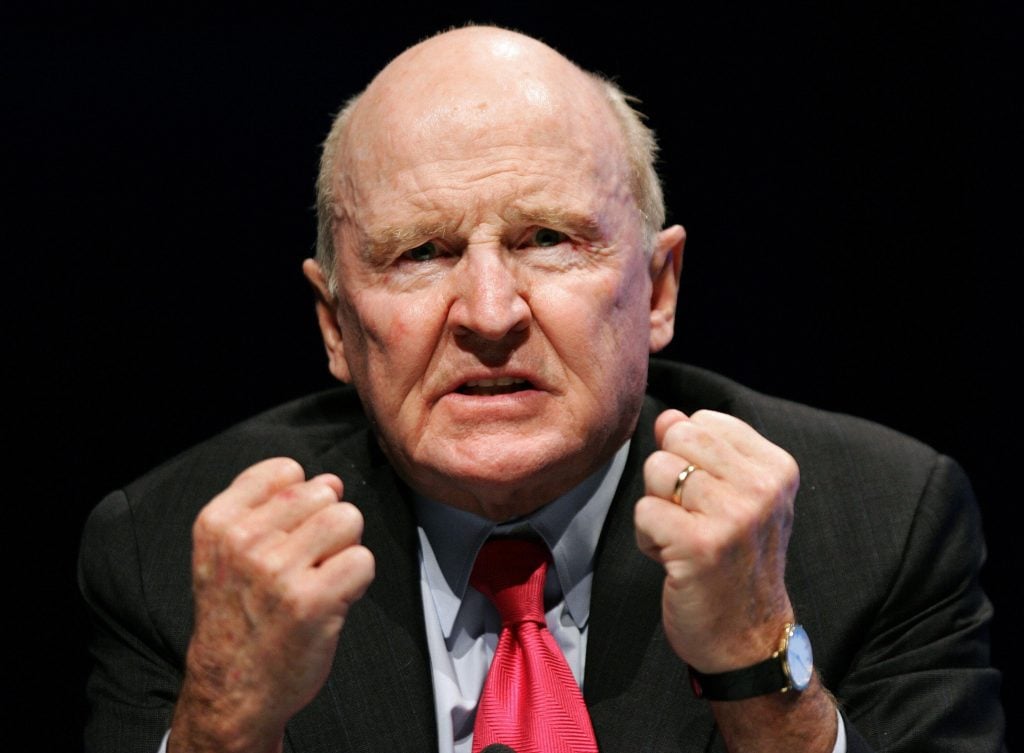

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation and Artnet Analytics.

The chart above plots seasonally adjusted data on after-tax U.S. corporate profits (courtesy of the U.S. Federal Reserve) against annual auction sales of fine art worldwide (courtesy of the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics). The sample period runs from 1988 (the earliest year for which we have comprehensive auction data) through 2021, covering most of Welch’s reign over G.E. and multiple decades of commerce directed by his acolytes and imitators.

While it’s true that correlation is not necessarily causation, the overall trend between these two metrics could not be clearer: as companies’ profits rose to new heights over the past 33 years, fine-art sales under the hammer followed closely along the same trajectory.

On some level, this dynamic seems obvious. “Of course rich people spent more money on the finer things as they, their companies, and/or the other businesses they invested in made more money,” you might be thinking. But the chart contains something more than that simple insight, and Welch is the key to unlocking it.

The issue isn’t that U.S. companies became outrageously more profitable in a post-Welch economy. By some standard metrics, they actually became much less profitable. Fed data shows that domestic corporations went from amassing about $825 billion in profits in 1981 (Welch’s first full year as G.E.’s CEO) to roughly $2.1 trillion in 2001 (the year he retired), a 2.5x increase during the first 20 years in which his example torqued global business strategy. From 1960 to 1980, however, corporate profits soared from $128 billion to $829 billion, a 6.5x increase—more than in any 20-year period of American commerce after Welch entered the C-suite in 1981.

In fact, looking through the lens of U.S. corporate profits actually undersells Welch’s impact on business strategy, wealth accumulation, and the art market for at least three important reasons. First, his techniques have been incorporated around the globe, not just domestically. (Seasonally adjusted data on worldwide corporate profits was not publicly available for all decades in question here.) Second, companies’ profits have had little, if anything, to do with their share prices and market capitalizations for much of the 21st century, especially in the tech industry. Just consider Uber, which went public in 2019 with an $82.4 billion IPO valuation and which still has not turned a net profit more than 13 years after its founding.

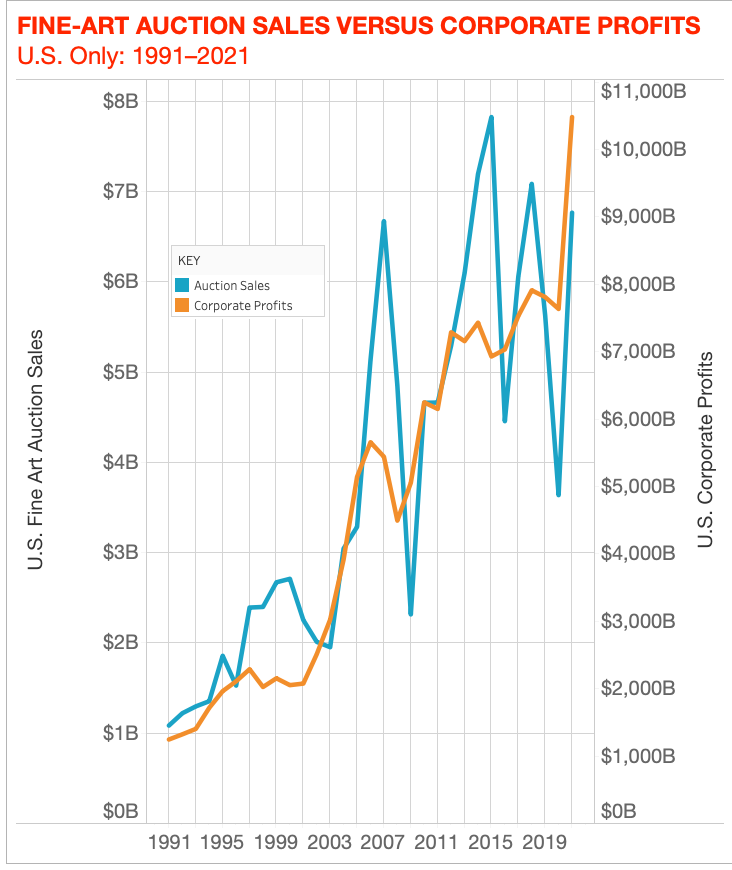

Then-CEO of General Electric Jack Welch speaks to the press in an undated photo. (Photo by Porter Gifford/Liaison)

Most of all, the high-end art market’s great debt to Welch comes from the changes he made to how corporate profits are redistributed—namely, to the investor/collector class alone. For comparison, Gelles noted in an interview that G.E. actually spent a portion of its 1953 annual report boasting about how well it was compensating its workers and how much money it was paying the government in taxes. But with Welch in charge, “Profits began flowing not back to workers in the form of higher wages, but to big investors in the form of stock buybacks.” (For the uninitiated, a buyback is the term for when a company acquires a large number of its own shares from the public markets to reduce supply and boost the value for existing shareholders.) The company also pioneered and perpetuated enough creative accounting techniques to shave its annual tax bill to the bone marrow.

Although this sea change made the rich far richer than ever before, chief executives arguably benefited most of all. CEO pay packages in the post-Welch economy became more wedded to their company’s stock-market performance than ever. This shift incentivized them to do what Wall Street wanted in the short term rather than what was best for their company in the long term. It also made the chief executives themselves fabulously rich.

A study by the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute found that, after adjusting for inflation, the realized compensation of U.S. CEOs rose by more than 1,300 percent between 1978 and 2020. (“Realized compensation” counts stock awards when vested and stock options when cashed in, an attempt to more accurately track chief executives’ earnings.) By contrast, the average American worker’s annual compensation rose a measly 13 percent during this stretch.

In fact, CEOs increasingly didn’t even have to be good at their jobs from Wall Street’s perspective in order to reap the type of outsized rewards that have engorged the art market. G.E. handed Welch a $417 million retirement package in September 2001, then “almost immediately… went into a tailspin from which it would never recover,” Gelles writes. Several of Welch’s proteges became CEOs elsewhere after inking contracts guaranteeing generational wealth even if they were fired shortly afterward (as they almost always were, according to Gelles).

Consequence-light corporate plutocracy has been a boon for high-end art dealers everywhere. But it’s not the only way that Welch’s influence has powered up the art market for better or for worse.

Andy Warhol’s Front and Back Dollar Bills (1962-63). Photo by Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby’s

It’s highly questionable whether Welch pumped up G.E.’s Wall Street worth by making it a better company, but it’s undeniable that he made it a different company. Here’s Gelles again:

But more than the downsizing or the dealmaking, it was Mr. Welch’s obsession with finance that allowed him to steadily inflate G.E.’s valuation in the public markets.

G.E. was an industrial company when he took over—making most of its money selling appliances, light bulbs, power turbines and jet engines. By the time he retired, the company derived much of its profit from G.E. Capital, which was essentially a giant unregulated bank. Mr. Welch called it “the blob”—it was an amorphous, ever-changing collection of financial assets, capable of delivering whatever adjustments were most advantageous to the parent company in a moment’s notice.

How important was G.E. Capital to the corporation as a whole? Gelles relays that it eventually made up 40 percent of G.E.’s revenue and 60 percent of its profits. In other words, Welch effectively transformed a producer of humble manufactured goods into a colossal financial instrument with Wall Street’s help—and was hailed as a hero for it. In this sense, his grandest innovation may have been to prove to the business world at large that almost anything could be securitized, borrowed against, or transformed into a derivative asset.

The art trade and the finance sector have thoroughly metabolized this idea in the decades since Welch’s reign. The outcome? An industry that once consisted entirely of buying and selling artworks has expanded to include loans collateralized by art, fractionalized ownership of individual pieces, investment funds in “portfolios” (aka collections) of paintings, and more.

Yet Welch’s financialization campaign also comes with a stern warning. Just eight years after his exit, G.E. settled what Gelles calls “sweeping accounting fraud charges with the Securities and Exchange Commission that pointed to decades of impropriety.” In the main, the SEC charged the company with knowingly overstating its returns to push up its share price, with the implication being that these nefarious tactics had been pioneered and perpetuated under Welch himself in the relentless pursuit of growth.

The art market has fallen victim to this same predatory impulse time and time again in the decades since new corporate wealth minted the modern mega-collector, since prices for single paintings in the U.S. spiked into the eight- and nine-figure realm, and since artworks began being recast as financial instruments. The more complexity the art trade has welcomed, and the higher the stakes of success and failure have become, the more opportunities have been created for an ongoing parade of scammers and other bad actors to capitalize on.

This is only a secondary impression compared to the mammoth footprint Jack Welch left on the art market without ever trying, but it bears remembering nonetheless. Like it or not, the art economy would not have scaled to its current size or worth without his warping of business strategy, amplification of investor- and executive-class wealth, and hunger to financialize whatever assets were available. The least we can do now is to stay on guard against the worst excesses of the blueprint he popularized. The most we can do is to search out different models altogether.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: the biggest consequences are often the unintended ones.