The Gray Market

How the Art and Music Industries Have Begun to Value Young Talent Differently—and Why It Matters

Our columnist investigates why fine art and pop music seem to have been taking opposite approaches to new talent since 2019.

Our columnist investigates why fine art and pop music seem to have been taking opposite approaches to new talent since 2019.

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, looking across the stage…

With New York’s fall auctions a week away and the economy feeling unsteady to many, more than a few art professionals are wondering whether bidders’ long-running enthusiasm for young artists will finally flag. The answer to that question will help establish how tethered the art market still is to larger business cycles. Just as importantly, however, it will indicate whether art sales are beginning to operate more like other cultural markets in the digital age, or continuing on the same bespoke path as they have for decades—and what that means for the art industry as a whole.

I’ve been thinking about this because of a feature in the latest Artnet News Pro Intelligence Report that uses data to analyze auction houses’ growing thirst for championing living artists at auction over the past 20 years. Written in conjunction with the Art Resources Team at Morgan Stanley, the piece takes a special interest in lots by ultra-contemporary artists (defined as those born in 1975 or later) offered by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips at their high-dollar, high-visibility evening sales.

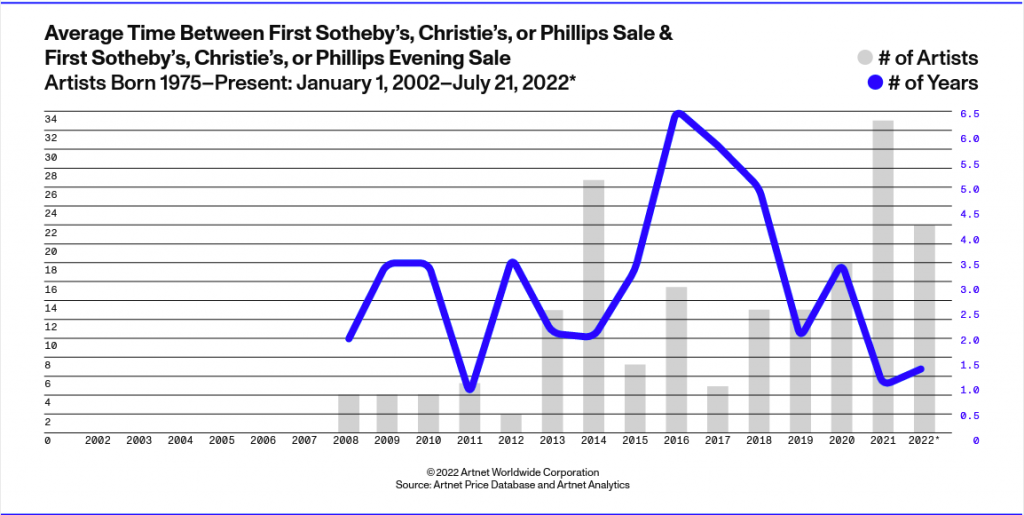

The big-picture findings? Younger artists haven’t just made the leap to an evening auction at one of the Big Three houses much faster on average than their older living counterparts over the same two-decade span. Since 2019, the number of ultra-contemporary artists making that jump has hit an unprecedented high while the time it takes to do so has hit an unprecedented low.

The data gels with the dominant narrative and heaps of anecdotal evidence. Just think about Sotheby’s recent decision to split what used to be called its contemporary evening sales into tandem nighttime auctions: “The Contemporary,” mostly made up of lots from the postwar era through the late 20th century; and “The Now,” mostly made up of lots completed in the 21st century, with hot ultra-contemporary names leading the way. Christie’s made a broadly similar move by reorganizing its fine-art sales into “20th century” and “21st century” events, though the chronological borders in both are slippery.

New auction initiatives have also been launched specifically around the once-sacrilegious concept of living artists (other than Damien Hirst, anyway) consigning fresh works straight to auction. Simon de Pury’s namesake auction platform kicked off the trend in the West with his much-discussed sale “Women: Art in Times of Chaos.” Sotheby’s followed shortly after by debuting its Artist’s Choice series, in which artists and their dealers jointly offer up select works right out of the studio. Both auctions were enormous successes, at least relative to presale estimates. They also reinforced the narrative that collectors have never been hungrier for up-and-coming talent than in the past few years.

These data points are all the more striking because, at first glance, they stand in direct opposition to what has been happening in another major cultural market over the same time period: music. But the lessons we can take away from this comparison aren’t quite what they seem on the surface.

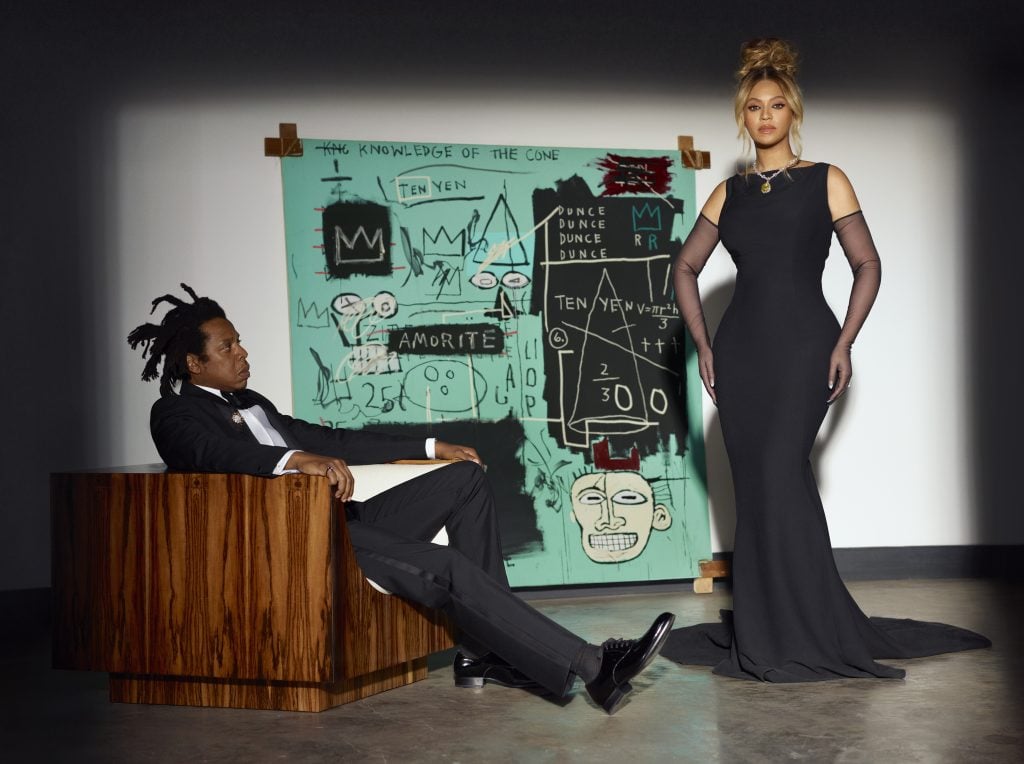

Beyoncé and Jay-Z with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Equals pi (1982) for the Tiffany & Co. fall 2021 About Love campaign. Photo by Mason Poole.

Let’s start with the biggest successes in modern pop. One metric for that designation is Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, which tries to capture the most listened-to pop music in the U.S. week to week. It turns out that the number of new artists in the Hot 100 has “declined precipitously” over the past 3.5 years, according to in-house editor Elias Leight. Here are a few specifics from his piece: “From 2001 to 2004, over 30 first-timers cracked the top 10 annually. In 2019, however, only 15 first-timers reached the top 10, and 2021 had the lowest number of new entrants this millennium: just 13.”

Why the sudden change? Leight’s sources offered a range of interlocking theories, starting with the never-ending avalanche of content churned out daily thanks to the music-streaming economy. A recent estimate from Universal and Warner Music Group pegged the number of new tracks being uploaded to Spotify every day at a staggering 100,000. The sheer volume makes it harder than ever for consensus to build around any one new song or new artist, especially since consumers tend to respond to overabundance by defaulting to artists or brands that are already familiar (a phenomenon I call the tyranny of options).

The collapse of the monoculture and the rise of TikTok have made matters even weirder. Here’s how Leight put it, with the help of an anonymous, frustrated industry insider:

“It used to be that you released an album, got Rolling Stone to review it, got on tour, got on late-night TV, and that was how you broke,” says one senior executive at a major label. Even if luck was a factor, the path was clear. “It was four or five things. Now you need four or five things a week, or at least a month, or else your streams don’t go up.”

Personally, I don’t think the same is quite true here in the art market, which underscores why I want to be careful about how far I analogize artists on the Hot 100 to artists whose work is included in evening sales at the Big Three auction houses. That said, in both cases, we’re dealing with the creators who have the highest visibility, the strongest market demand, and the greatest revenue-generating capacity relative to their peers in the field at that time. And while evening sales have no set number of lots from auction to auction, they nevertheless offer only a finite number of slots for a finite number of artists, just like the Hot 100. Those parallels give the comparison some validity.

This makes the aforementioned Artnet x Morgan Stanley data on ultra-contemporary artists’ acceleration to evening auctions all the more noteworthy, because lately the age dynamics in the Hot 100 have been the inverse of the age dynamics in Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips evening sales.

In 2021 alone, an all-time high of 33 ultra-contemporary artists made their first appearance in one of the Big Three auction houses’ evening sales, with another 22 new entrants doing the same by mid-July of 2022. Since 2019, artists in this cohort have also only needed between 1.2 years and 3.4 years on average to level up to an evening sale after their first appearance in a day sale at one of the same three houses. (The average was pressed down by a handful of cases where artists were able to skip the day sales entirely and go straight to prime time.)

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

In comparison, among living artists born between 1900 and 1974, no more than 26 have made an evening-sale debut at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, or Phillips in any year since 2019, and only eight had done so by mid-July of 2022. (In fact, no three consecutive years have introduced fewer new artists from this age group into a Big Three evening sale since 2004 through 2006.) This older group has also needed between 11.4 and 16.6 years to make the leap since 2019.

My working theory is that the opposite trend lines reflect that the business of high-end art has changed a lot less in recent years than the business of pop music (a theme I’ve written about at length before). Sure, there are a few edge cases where some previously unknown artist has thundered into the blue-chip auction market through nontraditional avenues (see: Beeple, KAWS). But to me, they are the exceptions that prove the rule.

The real question, however, is how much it really matters if a few dozen more or a few dozen fewer new artists earn a slot in a major evening sale or on the Hot 100 charts annually. The answer depends largely on whether you’re examining the phenomenon from the inside or the outside.

KAWS, New Morning (2012)and Gone (2020) (Photo by Ben Davis)

I was reminded of this split by Damon Krukowski, a longtime musician who now writes an excellent newsletter dissecting the business of the industry. Krukowski was a founding member of the dream-pop band Galaxie 500 from 1987 until its breakup in 1991, and he continues to write and perform with his Galaxie 500 bandmate (and partner) Naomi Yang under the name Damon & Naomi. He is also a driving force behind the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW), an informal trade association of self-employed artists and music pros advocating for more sustainable business practices in the streaming era. (More on that shortly.)

Krukowski feels that the panic over the drop in new artists on the Hot 100 is basically an extremely high-class problem, to the extent it’s a problem at all. The Billboard article, he said, represents “a rarefied part of the industry” to begin with, and the sense of crisis voiced by the label execs, talent scouts, managers, and other Big Pop stakeholders within it comes more from a tradition of unjustified self-promotion than anything else.

“There’s this premise that they can create a career, but in my opinion they can’t. It’s totally random,” he said—and it always has been. “That level of control is just a myth. You always run into these people who are telling you that they’re responsible for having broken so and so’s career, and it never happens twice.”

Fittingly, Krukowski and I spoke on the same day it was announced that Taylor Swift had become the first artist in history to occupy each of the top 10 spots on the Hot 100 simultaneously. On one hand, Swift’s milestone could be seen as extreme real-time proof that established artists are dominating the top of the pop charts like never before. On the other hand, it changes nothing about the larger realities of trying to build or maintain a career as a working musician or music professional in 2022.

“It’s always been a star-focused industry,” Krukowski said. “Whether it’s 10 or 100 stars, I don’t really care. It’s them versus all the rest of us.”

There’s no question this divide is repeated in the art market. Yes, artworks by more young artists than ever can be offered at the apex of the secondary market… and yes, this shift can remain all but irrelevant to the lives of about 99 percent of their peers. From there, however, the two industries part company in revealing ways.

Dancers in Soundsuits by artist Nick Cave perform during the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s annual Art Bash. Courtesy of San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images.

Let’s return to where we began: the effect of larger economic cycles on which types of artworks sell best during any time frame. I asked Krukowski whether the sell side of the music business has traditionally followed the same pattern as fine art, with distributors tending to fixate aggressively on up-and-coming talent during boom times, and to retreat from unproven acts during downturns. His answer was that it could have been a parallel prior to the streaming era—and, along with it, the growing monopolization of the industry by the major labels and outside financiers—but no longer.

To explain the landscape faced by a non-star musician in the streaming economy, Krukowski pulled up the Spotify data on Galaxie 500’s material. Their songs generate about 750,000 streams per month. Sounds pretty good, right? The problem is that it equates to roughly $2,250 in gross revenue, to be split between everyone involved: each member of the band, the label, the manager, etc. Since the margin on every album sold is about $10, he estimated, those three-quarter of a million monthly streams create about the same income as selling 225 records.

“At that point, you’re talking about below minimum wage,” he said. “So the streaming economy is based on these dazzling numbers that add up to zero.”

To analogize, then, streaming totals have about as much effect on most musicians’ livelihood as the number of Instagram likes or the number of visitors to a gallery show has on a living artist’s livelihood. It also clarifies that indie musicians are functioning on a scale much closer to working visual artists than the trappings of the art forms suggest. (Also, digital artists: if anyone offers to include your work in a streaming subscription of some kind, sprint in the opposite direction.)

The dismal economy of streaming foreshadows that the Hot 100 chart’s stasis is just one manifestation of a larger, more distressing trend. Longtime music writer and industry consultant Ted Gioia captured much of the problem in his viral essay “Old Music Is Killing New Music.”

As Gioia explains, research from music-analytics firm MRC Data found that songs released more than 18 months earlier—a category referred to as “catalog”—made up 70 percent of music consumption by the end of 2021. This is partly because listenership for old music increased by 19.3 percent from 2020 to 2021, while it actually regressed for new music by 3.7 percent over the same stretch. Case in point: the 200 most popular new songs accounted for just five percent of streams last year.

The distribution side is even more imbalanced. A 2019 study by Music Business Worldwide estimated that the Big Three record labels claimed about 80 percent of all royalties on streaming platforms circa 2019, and Gioia asserted on a recent podcast that the same labels spent $5 billion buying up the rights to old tunes in 2021 alone. A shock force of private-equity funds barreled in to spend generational wealth to acquire the rights to the catalogs of heavyweights like Bob Dylan, Stevie Nicks, and yes, Taylor Swift, among others.

Bob Dylan at work in his art studio. Photo courtesy MGM National Harbor.

Only the label execs know how much they’re spending to discover and promote new artists, but Gioia and Krukowski agree that it’s a fraction of a fraction of the total being spent on the old stuff. “It’s turned into a volume industry now from the labels’ point of view,” Krukowski said. “They’re leaning on catalog, but not necessarily on artists like the Beatles per se.”

This isn’t to say that distributors lack incentive (or even desire) to try to break new talent. But in a volume-based strategy, the likely return for investing resources in any one artist, genre, or category basically approaches the likely return for investing in any other. New acts, classic pop, ambient soundscapes on a “Music for Working” playlist, literal white noise to help listeners sleep—to some extent, the size of the catalog matters as much as its specific makeup, if not even more.

This is a vital point in any discussion that tries to connect the auction market to the music business. Most catalog material does not necessarily equate to lesser works by storied names like Jasper Johns, Yayoi Kusama, or Frida Kahlo, or even to work by promising artists striving to break out. It could just as easily equate to something like anonymous hotel art.

All of these factors make music much more of a winner-take-all market than fine art. Arguably Krukowski’s main beef is that the streaming economy and increased monopolization have forced independent musicians, who used to court different fans, sign to different labels, sell at different record stores, and play at different venues, to face off against the world’s biggest pop artists in all avenues. The real winners aren’t even the top-selling artists.

“There are only three major labels left, only three streaming platforms that matter (and really only one), and only two promoters handling all the shows. That’s a level of control that’s way, way deeper [than in the past],” Krukowski said. And still, he said, “it has no influence on who’s going to break through.”

The situation in music has gotten so bad that more than one-third of workers in the British music industry lost their jobs in 2020, and there are still about one-quarter fewer jobs there today than pre-COVID. In Krukowski’s words, if you’re trying to put together a U.K. tour, you literally can’t find people to drive the bus anymore. We don’t have comparable data for the U.S. fine-art industry, but it’s not that apocalyptic. Even the most demonstrable brain drain in the art world has at least some hope of being reversed by the historic union drives at museums since 2020.

This doesn’t mean that next week’s auctions are a meaningless indicator for the direction of the industry, especially as it concerns the resilience of rising artists. But it does mean that the art industry is still in a fundamentally different place than the music industry in terms of consolidation. In one sense, our field’s resistance to change may actually have prevented circumstances from deteriorating as much as they could have. But that also doesn’t mean things are as good as they should be for everyone involved.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember to keep your ears open even if you think you’re only hearing static in the moment.