The Gray Market

Progress Helped Destroy Silicon Valley Bank. Stasis Should Shield the Art Market

Our columnist explains why the death of Silicon Valley Bank makes the art market's traditionalism look wise for once.

Our columnist explains why the death of Silicon Valley Bank makes the art market's traditionalism look wise for once.

Tim Schneider

Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, on the safety of stubbornness…

The business story of the past week has been the astonishingly speedy collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and whether the U.S. government’s muscular response can prevent a larger crisis in the financial system. While much remains to be seen about the fallout as of publication time, analysts have been able to reach consensus on the factors most directly responsible for pushing SVB into insolvency. Among those factors, two of the headliners are the amplified efficiencies of banking in the 2020s and the accelerating power of social media among the tech and venture-capital sets.

Yet it’s the art market’s conspicuous lack of progress on these very same fronts that continues to safeguard even its most speculated-upon artists from suffering market failures as rapid as SVB’s. Ironically, then, this may in fact be the rare case where regulators of banking could learn something from the art business—despite the near-total lack of industry-specific regulations governing the latter.

If the screaming headlines around SVB’s cave-in have left you scratching your head, here’s my best gloss on what the hell just happened and why it matters. Silicon Valley Bank was, as the name suggests, a popular regional bank based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Founded in 1983, SVB carved out a niche for itself by doing business with early-stage tech startups that larger, more traditional banks often considered too risky to take on as clients.

As some of these startups became society-shaping, plutocrat-minting successes, the bank benefited in an outsized way. The Valley’s rampant follow-the-leader mentality also added strength to strength. Want to be the next unicorn startup or V.C. hero? Then entrust your money to SVB, just like your role models before you. In fact, one of the only traits more unusual than the extreme clubbiness of SVB’s clientele was the symbiosis between the bank and its customers. Business and finance journalist Liz Hoffman recently said on the Plain English podcast that SVB even started to echo its account holders’ pitch decks by slinging buzzwords like “innovation” and “burn rate” in its public communications instead of relying on standard finance principles like, say, “capital allocation” and “risk management.”

The business plan worked spectacularly during the pandemic. SVB’s deposits ballooned from $60 billion in 2019 to around $198 billion in the first quarter of 2022, according to the Net Interest Substack, as the bank’s tech-centric clients rang up stunning amounts of money during the COVID era. Those gains made SVB the 16th-largest bank in the U.S. at the time of its collapse.

So, what went wrong? And given how prevalent the financialization of the art trade has become, why shouldn’t we in the art trade be worried?

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Henrik Kam. Courtesy of SFMOMA.

At bottom, the vast majority of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure wasn’t just the result of an unforced error; it was the result of an unforced error that violated literally the most basic, first-day-of-class tenets of risk management. To understand where the bank messed up, it helps to review the core premise of how banks are supposed to work. (Note: If you’re a finance pro, feel free to skip down to the paragraph that opens with “Silicon Valley Bank got the balance wrong…”)

While the business of banking has become infinitely more complex than it was 100 years ago, contemporary banks still mainly follow one model: they borrow short to lend long. To oversimplify for the uninitiated, this means that they borrow money from their clients on a short-term basis, at whatever the corresponding government-set interest rate is at the time, and use the borrowed money to invest in bonds or loans with a higher interest rate that “mature” (or pay out) on a longer-term basis. Any bank that does this competently will make money in the aggregate.

What most individual bank customers don’t think about most of the time (and may not even know at all) is that it’s their deposits that the bank is borrowing short to lend long. Normally, though, this fact is irrelevant. Banks are only allowed to borrow deposits because they also guarantee that account holders can withdraw any amount of their deposited money any time during regular business hours.

This arrangement isn’t the contradiction it sounds like at first. Why? Because most customers at any bank usually only withdraw relatively small amounts of their money in the short term. Which means that banks only need to keep a fraction of their overall deposits in cash to honor their end of the bargain.

The minimum size of that fraction is determined by government regulations. Beyond this baseline, it’s up to each bank’s risk managers to decide how much more cash, if any, to keep on hand. The rest of the money goes into the bank’s lending (see: investment) portfolio for profit-generating and contingency purposes.

Like any individual or institutional investment portfolio, every bank’s portfolio should contain a mix of assets with different levels of risk and, in the case of bonds and loans, different timelines to mature. One difference, however, is that regulations require banks to declare at the time of purchase whether they plan to hold a given asset to maturity or keep it available for sale to raise cash quickly.

The challenge in the foundational business of banking is that when interest rates change, a bank’s lending portfolio has to change, too. Higher interest rates mean, first, that a bank has to pay more to borrow its customers’ deposits than it used to, and second, that some of the bonds and loans the bank already invested in when the cost of borrowing was low might not be returning more money than the new, higher interest rate. If a bank’s strategy can’t be adjusted nimbly, then it will start losing money, and its investors will notice. Then, if its investors start selling shares of the bank’s less valuable stock to cut their own losses, and depositors start pulling out their deposits because of the crashing stock price, the bank’s dizzy spell can quickly transform into a death spiral.

In a very basic sense, then, every bank divides its money between three buckets: cash (for customer withdrawals); held-to-maturity investments (for long-term upside); and available-for-sale investments (for short-term financial flexibility). How, and how much, it chooses to fill up each of those buckets largely determines each bank’s fortunes, both literally and figuratively. Get the balance right, and a bank can power up in a major way. Get the balance wrong, and a bank can disintegrate into dust.

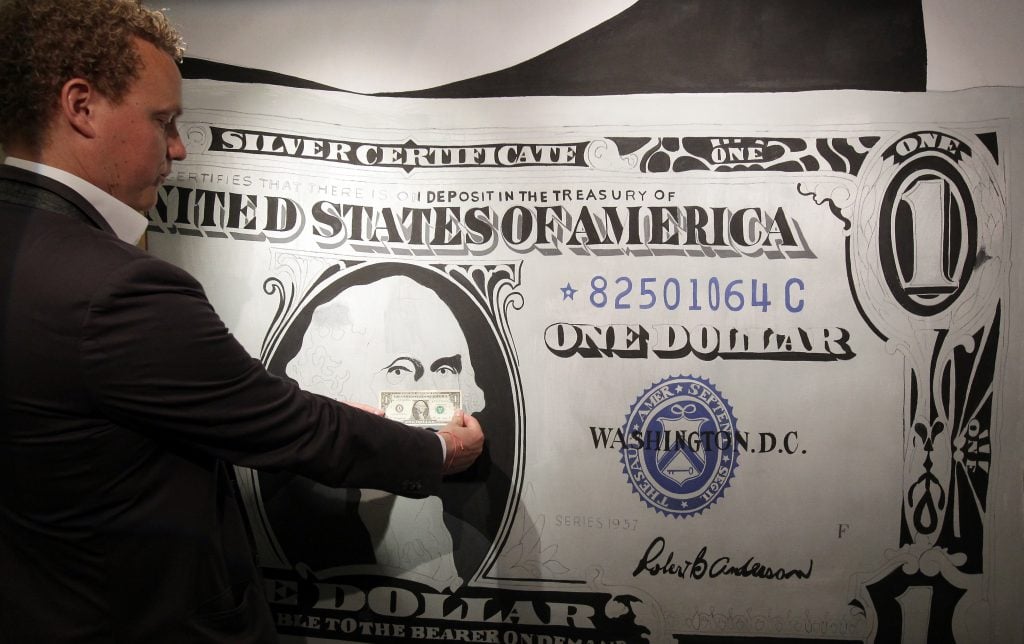

Andy Warhol’s One Dollar Bill (Silver Certificate) (1962) shown at the media preview of the summer auction at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in May 2015. (Photo by Dickson Lee/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

Silicon Valley Bank got the balance wrong—spectacularly, stupefyingly wrong. At its peak size of $198 billion worth of deposits in Q1 of 2022, SVB’s portfolio had only $27.3 billion in assets available for sale, versus $98.7 billion in assets it had promised to hold to maturity. That meant that if an abnormally large number of SVB account holders were to decide for some reason that they needed to withdraw abnormally large chunks of their deposited money, and SVB’s cash reserves were too low to fulfill its obligations to those customers, then very little of its portfolio could actually be sold off to make up the difference.

Well, “for some reason” happened. To put it bluntly, the financial markets have sucked for the past year. One major cause? To combat runaway inflation, the Federal Reserve has ratcheted up interest rates the farthest and fastest in four decades, with its policy rate ascending from near zero in early 2022 to between 4.5 percent and 4.75 percent in February 2023.

That’s been bad for investors, but it’s been worse for companies that had been planning to raise money during this stretch, either by going public or by going back to venture capitalists. As rising rates and declining portfolio values have made the public and private investment markets more risk-averse, many of these capital-hungry companies have had no choice but to start drawing on their existing cash reserves to stay alive until conditions improve.

Among them were dozens and dozens of tech startups banked with SVB. Deposits there fell by $33 billion (about 17 percent) between the end of March 2022 and the end of February 2023, according to Net Interest. That left the bank with $165 billion worth of deposits entering March, the overwhelming majority of which had already been committed to assets it could not sell because it had promised to hold them to maturity.

That asset allocation made more sense in the low- or no-interest rate environment that investors enjoyed for most of the past 14 years. But it was inexcusable for the bank’s leaders not to adjust their strategy as it became clearer and clearer that higher rates were coming, especially since SVB CEO Greg Becker was a member of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s board of directors. This means, as journalist and podcaster Derek Thompson put it, “The SVB team had taken out a long position on low interest rates while its CEO was a core member of the group in charge of raising interest rates.” This is, quite frankly, one of the dumbest things I have ever heard of in the world of finance.

As February turned to March, SVB found itself squeezed between its dwindling deposits, the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes, and its retrograde asset allocation. As its ability to meet customers’ requests for their deposits shrank, the bank’s leadership realized it had to sell off some of its available lending portfolio at a loss to cover the difference.

Once the bank revealed that fact vis-à-vis its larger portfolio imbalance in its disclosures to investors and clients, it sparked an old-fashioned financial panic. First, investors (not account holders) started abandoning the bank en masse; SVB stock plummeted 60 percent in just one week in March. Then SVB customers began frantically withdrawing funds. The frenzy peaked on March 9, when account holders pulled out a bone-crushing $42 billion worth of deposits—the single largest bank run in history.

This dual disaster hit SVB too hard and too fast for it to raise enough money from institutional investors to offset the losses. When it came time to open its doors on March 10, SVB was insolvent, and the government swept in to take control of its assets and try to prevent the damage from radiating out to the rest of the banking system. (Two other regional banks, Signature and Silvergate, went belly up in the days surrounding SVB’s seizure.) And it’s this fatal avalanche of withdrawals that contrasts so sharply with the art market.

Berlin Biennale, Venice Runs (2015).

Courtesy Berlin Biennale für zeitgenössische Kunst / for Contemporary Art.

By early this week, one of the main lessons to emerge from the financial media was that SVB’s death blow would go down in history as the first “social-media bank run.” The idea might sound odd, given that Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms were all up and running by the time of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. But compared to now, their reach back then was T-Rex-armed. Twitter counted just 6 million active users in 2008, versus 368 million as of December 2022. Facebook had 100 million active users in 2008, versus just under 3 billion as of December 2022.

While those are mammoth increases, I would argue that they still undersell social media’s contemporary influence over events of national and global importance. This is especially true in the case of SVB’s collapse, as Bloomberg’s Matt Levine noted on Monday:

SVB’s depositors, who again are largely tech firms and venture capitalists, are all on Twitter a lot and move in herds; when they noticed that SVB was insolvent-ish they all pulled their money out at once. (“It turned out that one of the biggest risks to our business model was catering to a very tightly knit group of investors who exhibit herd-like mentalities,” an SVB executive told the Financial Times.)

It’s just another situation where a technology engineered to amplify extreme opinions irrespective of their relationship to truth, credibility, or glaring self-interest did exactly that in a high-leverage moment. First, a small group of extremely online people with large audiences incited one panic about SVB’s financial health, encouraging a blitz of withdrawals. Then, many of the same people incited another panic about what would happen if SVB customers who failed to pull their deposits in time weren’t bailed out by Uncle Sam. (Nevermind that many, if not most, of the people in danger were wealthy libertarians who had spent years bellowing about how the nanny state needed to roll back regulations and let entrepreneurs work their magic for the good of humankind.)

Still, the frenzy might not have been fatal to SVB if not for advances in banking technology that enabled the crowds to act with newfound velocity. In earlier bank runs, customers could only withdraw their deposits by getting a bank rep on the phone or going down to their branch in person. Now, every bank has an app, meaning customers can move money from their phones at a moment’s notice, no matter where they may be or why they might be spooked about the prospect of imminent financial ruin.

It’s true that banking and art sales still differ in vital ways, but they converge when it comes to the phenomenon of large-scale desertion by patrons. Since the early 2010s, more and more young artists’ careers have been lifted up fast, then dashed on the rocks even faster by speculative buyers-turned-sellers. The overall arc of those stories traces the story of SVB in important respects. All of them are made possible by accelerated trend-following among a subset of elites on the way up and the way down alike.

Look at it like this: A broad base of prestige- and profit-chasers in tech and venture capital was eager to bank with SVB for years, until a critical mass of agenda-setters started passing along word that they were all dumping SVB ASAP… just like a sizable group of prestige- and profit-chasers in the art market was desperate to buy, say, a Lucien Smith “Rain” painting, or more recently, a Jordy Kerwick wildlife canvas, until a critical mass of agenda-setters started trying to dump those same artists’ work ASAP. (My colleague Katya Kazakina reported in late February that auction houses “are saying no to countless works by” Kerwick, one of the stars of last year’s ultra-contemporary genre, due to lack of confidence that they’ll outperform 2022 auction prices.)

The difference is that the art market in 2023 has made very few of the efficiency gains that now define banking. Turning artwork into cash remains a slow, laborious game. Advances in e-commerce make it simpler to consign or offer works than in the past, but context matters tremendously to results; the easiest places to list an artwork online are, with rare exceptions, unlikely to attract high-quality buyers.

The more traditional avenues still often take weeks or months to process. Consigning a piece to auction (even an online-only auction) usually means a bare minimum of five or six weeks of lead time before the sale goes live, then one to three months before payment arrives. That’s assuming the work sells at all, or the house will even agree to offer it in the first place. Consigning to a private dealer can be even more unpredictable. The work might sell in a few days during boom times, or it might languish in storage for a year depending on the larger state of the market.

Although the rise of art finance and fractional-investment platforms make artworks more liquid than they used to be, that’s a low hurdle. These new tools still require due diligence and/or a willing counterparty to transform art into money. Even Masterworks’s secondary market for fractional shares is only as valuable as the number of buyers ready to pay a user’s chosen resale price. These traits keep the art market lagging lightyears behind the one-tap-away accessibility of modern banking.

The two industries diverge when it comes to social media’s accelerating power, too. As Levine noted, Twitter is the one true online home of tech and venture capital. The relatively small share of the art industry on Twitter, on the other hand, contains very few of the market-making, agenda-setting, or policy-shaping types whose equivalents in the Valley regularly tweet to strengthen their own advantage. To me, it’s a natural outgrowth of art’s status as an exclusive, niche market, where moving broader public opinion tends to have almost no tangible benefit to the stakeholders doing the pushing. Instead, the art establishment concentrates almost exclusively on Instagram, which has demonstrated much less capacity to influence decision-making at scale through viral posting in any context.

Even if these different business sectors paralleled one another in their social media use, however, the old-school infrastructure of art sales would still stop any panic sales from reaching the intensity of the bank run that doomed SVB. That might sound like damning with faint praise. But for once, I genuinely think stasis is doing us more good than harm in the art market, and there are very few reasons to expect that to change anytime soon.

[Dealbook / Bloomberg / The Atlantic]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: progress only matters if the destination is better than the origin point.