Artnet News Pro

The Fight Against Flippers: How Artists and Dealers Are Trying to Beat Speculators at Their Own Game

Rampant speculation has turned the market for emerging art upside down. Now, artists are determined to wrest back control.

Rampant speculation has turned the market for emerging art upside down. Now, artists are determined to wrest back control.

Katya Kazakina

A version of this article originally appeared in the Artnet News Pro fall 2022 Intelligence Report.

Collector Jacobo Garcia Gil made an unusual confession to his Instagram followers this summer. He outed himself as the seller of a painting by emerging artist Adriana Oliver at a forthcoming Phillips auction in Hong Kong.

“It’s a long-term project that I’ve been working on with Adriana,” he said. “She’s fully aware, and she has been collaborating.”

Garcia Gil bought April of 1958 for about $3,600 from the artist’s first solo show in 2018. Painted in a flat style that evokes Julian Opie and Tom Wesselmann, it depicts a dark-haired man in a suit, his face blank. Phillips estimated it would bring in $12,700 to $19,110. The final price was $19,300, including fees.

Going public about flipping a painting was noteworthy. Although widespread, speculative trading used to be anathema to the art world. Galleries like to control prices and access, and auction sales interfere with both, potentially hurting an artist’s long-term prospects when the demand dries up. Garcia Gil consigned the work to Phillips to position Oliver as part of the Spanish New Wave, a catchy brand name for a group of young Spanish artists—including Javier Calleja, Edgar Plans, Cristina BanBan, and Jordi Ribes—with strong auction followings.

Although Oliver, 32, is far from a household name, her solo shows have all sold out and her auction sales have generated $436,504 since 2020, according to the Artnet Price Database. About a third of the 95 lots by Oliver at auction have been offered at Japan’s SBI Art Auction, dubbed by Garcia Gil “the House of Flippers.” (A representative for SBI said they were unfamiliar with this moniker, and that clients frequently refer to them as “the House of the Trendsetter.”)

“We cannot stop the flippers in Japan,” Garcia Gil recalled telling Oliver. “Instead of trying to fight them, let’s join them. I’d rather take you to a global auction. If I position you within an art movement, everyone wins.”

She wasn’t entirely convinced. The sale went ahead anyway.

Flipping is the bête noire of the art world—and the volume and velocity of these transactions have never been higher than right now.

Sales of works by ultra-contemporary artists (those born after 1974) offered at auction within three years of their creation soared to $257.4 million in 2021 from $22.8 million in 2012. That’s a 1,000 percent increase over the course of a decade. Over the same period, the S&P 500, which had also been on a tear, rose just about 200 percent.

Of course, these figures don’t account for inflation or the carrying costs of buying and selling art, including auction-house fees, insurance, and storage. Those can (and do) add up. But in the public imagination, art is one of the best investments out there, and a growing number of platforms are luring uninformed investors into the fold with the promise of helping them find the next Basquiat or KAWS.

The Now Evening Auction at Sotheby’s in May 2022. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

As speculation becomes more widespread, the attitude toward it is changing. It’s not a matter of if a hot artist ends up at auction, but how quickly. There was a time when emerging art wouldn’t even make it to the auction block. More recently, young artists would be first tested in day sales. Now, little-known names are routinely launched at the most glamorous and high-stakes evening sales in New York, London, and Hong Kong.

In 2021, artworks created a year before generated $139 million at auction, 10 times more than a decade earlier, according to the Artnet Price Database. During the same period, the average amount of time it took for an artist to ascend from the day to evening sales at one of the Big Three houses shrank to less than 18 months from three and a half years.

“It is a problem,” said Jack Shainman, whose gallery represents popular artists Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Nina Chanel Abney. “It always has been. It’s worse than ever now.”

Artists and their galleries, who rarely benefit directly from these resales, are fighting back. Some artists now withhold their best works from the market and hire managers to help them navigate the terrain alongside their galleries. Dealers circulate blacklists of repeat offenders and expect a percentage of the upside when clients resell works. Businesses have sprung up to level the playing field between new talents and those who make a quick buck speculating on their work.

“There’s a huge inequality in the art world and the art market in the way we look at creativity,” said Lucien Smith, a poster child of the previous flipping craze, whose work became a hotly traded auction commodity in 2014.

To solve this problem, Smith partnered with a tech and data startup, Lobus. Together they are working to create a platform powered by blockchain technology where artists and galleries receive 10 percent of every trade, no matter how big or small. In this new system, those blacklisted flippers can come back into the fold and have a positive effect, Smith said.

“We are going to see the day-trader collector,” he predicted. “A collector who sits on the computer and monitors the PR and shows and museums and what collectors are buying. They’ll soak up everything they see where there’s a possibility to profit. And a portion of those transactions will be given to the original artists and galleries.”

Smith’s “Rain” paintings—made by spraying canvases with paint from a fire extinguisher—soared to $372,120 and were routinely traded in the low six figures less than a decade ago. Then the music stopped. Collectors of new art began liquidating, fearful their investments would go down to zero. In 2014, art sold within three years of its creation date generated $73.2 million at auction; three years later, that number dropped to just $25.2 million.

“Everyone thought it was a negative experience,” Smith said. “I turned it into a positive one. My market was bound to go down, especially when I stopped making art at the rate I was making it. I didn’t want to keep putting hard work into a system that was broken. I focused on fixing that system.”

Amani Lewis, Negroes in the Trees #3(2019). Image, courtesy the artist and Destinee Ross-Sutton 2020.

Smith is not alone in trying to figure out how to get artists to benefit from their secondary markets. A growing number of galleries have started consigning works by emerging artists directly to auction. In 2020 and 2021, dealer and curator Destinee Ross-Sutton partnered with Christie’s on sales of new work by Black artists; 100 percent of the proceeds went to the creators, and buyers had to agree not to resell the works for at least three years. Baltimore-based Galerie Myrtis also sold work by six contemporary Black artists at Christie’s in September.

Meanwhile, Sotheby’s launched Artist’s Choice, an initiative to get consignments directly from artists and their galleries, with a portion of the sale price going to charities of the artists’ choosing. The results of the first offering were strong: six works, all priced between $15,000 and $120,000 each, realized a combined $919,800, tripling expectations.

Then, this month, Art Basel and the Luma Foundation teamed up to launch Arcual, a custom digital ledger that hosts smart contracts that enhance artists and dealers’ control over the life of an artwork and can embed resale royalties into each transaction.

These initiatives bubbled up after broader reforms failed. Lawmakers have tried unsuccessfully to pass federal legislation to help artists secure a resale royalty from auction sales at least eight times since 1978. Other creative industries, including music and publishing, reward musicians and writers with royalties, but, at least in the U.S.—the largest auction market in the world—artists still come up dry.

While artists like Gerhard Richter and Jeff Koons are notoriously involved in their markets, most still prefer to focus on making art and leave the selling and marketing to their galleries, which typically receive 50 percent of each primary-market sale.

Prices for emerging art that makes it into the art-world ecosystem usually start below $10,000 and go up incrementally from there. Galleries are loath to raise prices even when artists’ secondary markets explode, in part not to price out public institutions, which have limited resources. This creates an absurd disconnect: the artists who make the work are left behind, unable to profit directly from their own success.

Artist Robert Rauschenberg photographed in August 1966. (Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images)

Things can get emotional. Robert Rauschenberg famously pushed his patron Robert Scull during the 1973 auction of 50 contemporary artworks from Scull’s collection at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet, where the artist’s Thaw fetched $85,000. Scull had bought it 14 years earlier for $900. “I’ve been working my ass off for you to make that profit,” Rauschenberg said angrily at the time.

Prices get vertiginous when there are more potential buyers than available artworks. Galleries restrict access to loyal clients and institutions. Everyone else has to compete for the coveted works on the secondary market. With each bubble cycle, the delta between primary and secondary prices gets wider and wider, and the potential profit for those with early access gets more and more attractive.

After the Scull auction, flipping resurfaced in the 1980s, when contemporary art began to draw global attention. “Somebody would come into a gallery, buy something for, say, $25,000, then go sell it at auction the next week for 40 [$40,000],” the painter Donald Sultan recalled in Artforum in 2003.

Traders at the Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. in Nihombashi, Tokyo. (Photo by Gerhard Joren/LightRocket via Getty Images)

When the Japanese stock-market crash cast a pall over the art market, young artists retreated from the auction-house limelight. But flipping returned during the heady years just before the financial crisis in 2008, which left many a busted career in its wake (remember Anselm Reyle?).

Then, all was quiet on the emerging-art front until 2014, when work by the so called Zombie Formalists—young, mostly male painters who used novel, bro-ey processes to create abstract paintings that looked good above the couch—began to sell for big prices. Los Angeles-based entrepreneur Stefan Simchowitz emerged as a flipper extraordinaire pushing this movement. After it went bust, he became active in the markets of a number of Black and female artists.

The Mugrabi family is also known for buying large quantities of primary-market artworks from artists including George Condo, KAWS, and Joel Mesler, then flipping them at auction over the years.

“People realized that emerging art had the ability to be a major financial vehicle,” said Bennett Roberts, coowner of Roberts Projects in Los Angeles, which represents Amoako Boafo, whose auction sales have generated $28.1 million since he burst onto the scene in 2019. In an effort to control his own market, Boafo was part of a group that won his painting The Lemon Bathing Suit (2019) at Phillips in early 2020 for an estimate-smashing $880,971.

“The art business has become a financial business,” Roberts said. “We can’t pretend that it’s not.”

Some market players are looking for innovative ways to help artists benefit when their work is resold. One of these is veteran auctioneer Simon de Pury, whose recently organized online auction, titled “Women: Art in Times of Chaos,” was crafted to weed out speculative sellers. Featuring works by such in-demand artists as Genieve Figgis and Chloe Wise, all of them consigned directly by the artist and gallery, it generated $831,310.

Genieve Figgis, Dreaming of Spring With Birds (2022). Image courtesy the artist and de Pury.

The proceeds were distributed back to the artists and dealers, who received the full hammer price to share however they typically split sales. De Pury also shared the identities of the purchasers and the underbidders. The crucial intelligence usually goes to the auction houses, to the detriment of the galleries and artists, he said.

“It’s just a novel way of looking at” the old process, de Pury noted. “And making sure that the artists and galleries—who create the art and champion it—benefit.”

A similar motivation underlies Fairchain, a startup that seeks to “square the tension” between the primary and secondary markets, according to its cofounder, Max Kendrick, whose father is sculptor Mel Kendrick.

The team at Fairchain. Courtesy Fairchain.

Fairchain registers the sale of an artwork with a digital contract that serves as a certificate of authenticity and follows the work in perpetuity. Each time the artwork gets sold, the artist receives a resale royalty, the exact size of which is determined by the artist and their dealer.

“It really hurts an artist’s feelings when someone resells,” said Ellie Rines, owner of 56 Henry gallery, who signed up for Fairchain. “But it doesn’t have to be that personal. Fairchain helps soften the blow.”

Sotheby’s new Artist’s Choice initiative aims to create a path for artists and their galleries to capture the upside from their secondary-market sales through auction. The answer, according to executive Noah Horowitz, is to consign directly in an open and transparent way, eliminating the speculator. Artists receive the hammer price of the sale and donate 7.5 percent to a charity of their choice. Sotheby’s will match that amount (it will come out of its commission, known as buyer’s premium).

“It’s a win-win,” Horowitz said.

Getting something back from the auction houses would be meaningful and psychologically healing for artists, said painter Shara Hughes, whose work generated $24.6 million at auction in the first six months of 2022.

“If the auction houses, buyers or sellers would give even a very small percentage back to the artist, especially living artists, to recognize that they are still working and can contribute to their studio in any way,” Hughes said, “I think that would validate a continuing practice way more than feeling taken advantage of.”

Rines, whose gallery was the first to show rising star Anna Weyant, said she understands buyers’ need to sell their art purchases. A painting bought for a few thousand dollars can suddenly become valuable enough to be a down payment on a house. Weyant achieved her auction record of $1.6 million just three years after debuting at 56 Henry.

“There’s a good way to go about it and a bad way to go about it,” Rines said. “The bad way is to put a painting up at auction. The good way is to offer it back to the gallery. You want to keep the resale as private as possible so that the market doesn’t become part of the conversation.”

She expects collectors to give her a percentage of the upside from a resale—even when they resell it through another venue. If not, she will restrict their access to future purchases, she said.

“I sold it to them,” Rines said. “I did them a huge favor.”

Galleries also push back by sharing information about bad actors in the form of blacklists.

Dana Schutz, Shooting on the Air (2016). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

“Blacklists do happen, but they are not as scary as they sound,” said Rachel Uffner, who until recently represented Shara Hughes. “If an artist I work with tells me, ‘I don’t want to sell to this person,’ I don’t sell to this person.”

To punish flippers, galleries have also shared their names with the press. In 2019, David Zwirner gallery leaked the name of Japanese collector Takumi Ikeda to Artnet News when he consigned a painting by Dana Schutz, who is represented by the gallery, to Christie’s, where it fetched $1.1 million. Ikeda didn’t originally buy the work from Zwirner.

Similarly, a director of Anton Kern Gallery leaked the name of the seller of a Julie Curtiss painting at Sotheby’s in 2020. The collector, Evan Ruster, was a longtime client of Anton Kern, but he picked up the work at the Spring/ Break art fair in 2017, long before Curtiss began working with the gallery. It fetched $210,300.

Ruster said he thought about sharing some of the upside with the artist but changed his mind after being outed. That situation still reverberates, he added, and in some cases negatively impacts his ability to acquire works by emerging artists.

“I bought a lot of art that I couldn’t sell for a dollar,” said Ruster, who’s been collecting art for more than 25 years. “It was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.”

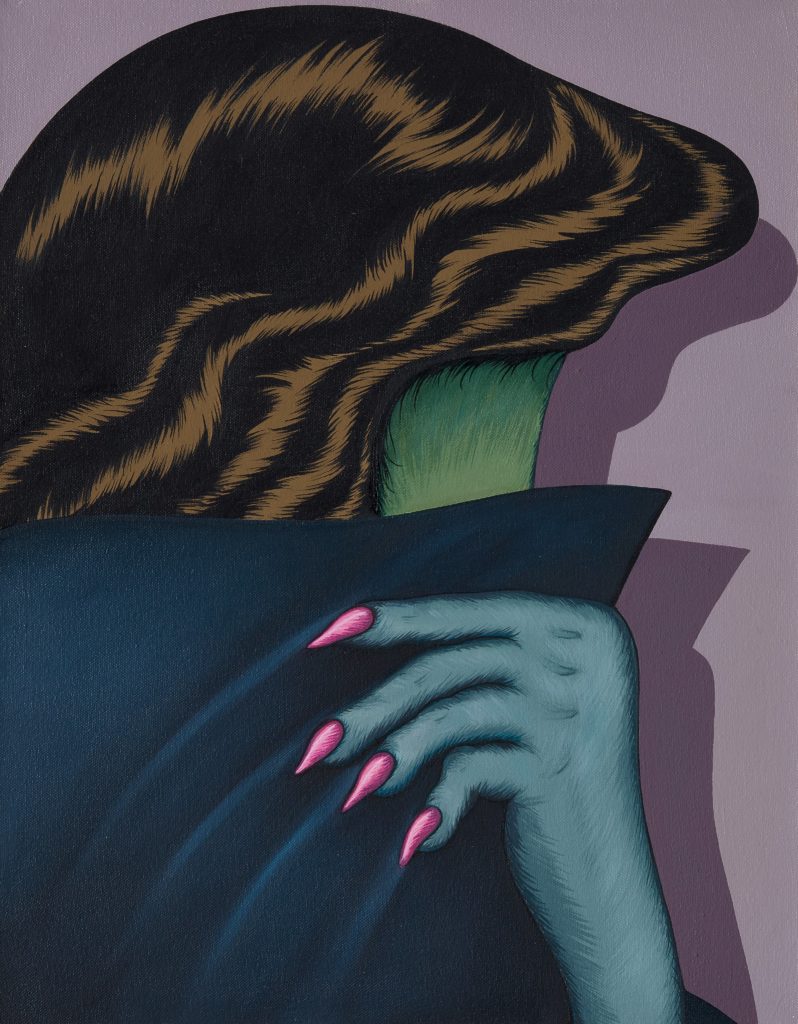

Julie Curtiss, Witch (2017). Courtesy of Sotheby’s Images Ltd.

Galleries say that they do their best to vet potential buyers and prioritize important collectors and museums whenever possible. But the reality is more complex.

“Most people want to keep their good standing in the art world, but it turns out that certain figures are too hard for people to ignore,” Uffner said. “Even multibillionaires sometimes resell.”

Howard Rachofsky, a major benefactor of the Dallas Museum of Art, flipped a painting by Christina Quarles, The Night That Fell Upon Us Up On Us (2019), at Sotheby’s for record $4.5 million in May, after buying it from Regen Projects in Los Angeles, according to a person familiar with the transaction. “You sell one to get 20,” said the person. Rachofsky, who didn’t respond to requests seeking comment, proactively offered part of the upside to the artist and Regen Projects, the person said. In addition, he bought another painting by Quarles, who is now represented by Hauser & Wirth, for the museum with the blessing of its curator.

Such voluntary resale royalty transfers are not customary, but they do happen. Collectors most commonly offer between 3 to 10 percent of the upside. “I’ve seen 20 percent but that’s rare,” Uffner noted.

Shainman said that one collector sent a $1 million check to the artist he flipped. The gallerist declined to elaborate, but remarked that “it’s highly unusual.”

Suing a wealthy patron for flipping a painting is normally the last resort for a gallery. That is why, in addition to employing technological and social measures, artists are increasingly seeking legal advice on beefing up their sales contracts. Megan Noh, a partner at Pryor Cashman LLP in New York, recommends that clients consider crafting invoices that make them third-party beneficiaries. “In case these provisions are breached, the artist will be able to bring a lawsuit,” she said.

She is also a fan of “contractual provisions that require a buyer who resells work to share a percentage of their resale profit with the artist.”

This requirement is part of a menu of provisions available to artists. Others include a period during which the artwork can’t be sold at all and a right of first refusal for the artist or the artist’s gallery. The non-resale periods vary but often range from three to five years, according to lawyers and dealers.

“I am trying to advocate for the artists and show how the artists and galleries can collaborate and share the burden,” Noh said. “It’s to everybody’s benefit to be able to control the market.”

Although Noh insists that the properly written contracts are enforceable under U.S. law, some doubt the efficacy of the legal approach.

Collectors routinely disregard their contractual agreements, dealers and advisors say. They simply sell off the remainder of their “no resale” term to an eager buyer who might not have access through the gallery, with a stipulation that the work can’t appear on social media.

Sellers may even be willing to take a cut in price to “bury things,” making sure that the galleries don’t find out. “They are paying for silence,” said advisor Saara Pritchard, who has represented buyers in such deals. “I usually ask, ‘Do you need a high price, or do you want it buried?’”

Adriana Oliver, April of 1958 (2018). Courtesy of Phillips.

Artists who aren’t armed with contracts or who don’t get a say in a sale can end up feeling raw. Oliver, the Spanish artist whose work was openly sold at Phillips by her longtime patron, is still processing the experience.

“He told me he wanted to finance other projects,” Oliver said. “And he kept saying that it’s good for me. I don’t think it’s good for me. I never confirmed or said, ‘Let’s do it.’ I just saw that the work was at auction. I was pretty angry.”

Not having a direct stake in the machinations can feel powerless. “It hurts your soul,” Oliver said.

To download the full fall 2022 Artnet Intelligence Report, available exclusively to Artnet News Pro members, click here.