Opinion

The Gray Market: Why Online Art Fairs Aren’t Solving the ‘Fairtigue’ Problem (and Other Insights)

Fresh off Art Basel's latest online viewing rooms, our columnist explains why virtual fairs are still exhausting the art world.

Fresh off Art Basel's latest online viewing rooms, our columnist explains why virtual fairs are still exhausting the art world.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, thinking that efficiency isn’t enough…

On Wednesday, the 2020 edition of “Art Basel” “opened”—meaning, of course, that the grim necessities of the ongoing public-health fiasco forced what is normally the world’s premier European (and arguably, global) art fair to launch its latest limited-run e-commerce website. And those in the art industry who are still fortunate enough to be either employed or running a business with a legitimate chance at making money in the midst of this absolute junkyard blaze of a year mostly tried to lean in and make the best of the infamous New Normal.

However, a brief exchange I had this week got me thinking about the bigger picture.

Just before the Art Basel viewing rooms went live, someone in the industry said to me, with a mix of wonder and exhaustion, “Do you believe that we’re already doing another one of these? So many virtual fairs!”

To which my response was: You do realize this is the same fair schedule we’ve been on for years, right? And that until the past three months, it was actually even more demanding, because we were all jumping on planes and swanning around cities and uprooting our lives for a week at a time to be a part of the tangible versions of these same events?

I don’t want to downplay the practical and psychological pressures that the lockdown and the national civil-rights uprising have put on anyone lacking the ability and inclination to retreat to a scenic country home. Simply surviving every day physically and mentally intact requires more effort than many of us have put forth in our lifetime.

It’s also true that the ban on tangible exhibitions and other IRL events has compelled galleries, fairs, and institutions to overcompensate with digital stand-ins of all kinds, as my colleague Nate Freeman covered a few weeks ago.

That said, there is no earthly way in which clicking around online viewing rooms is a heavier lift than physically participating in art fairs.

Is it more frustrating? I’d say yes. By this point, every new glitch-ridden Zoom meeting pushes me closer to driving a letter opener through my laptop camera like I’m trying to stake a vampire. I’d rather spend a full day trying to make sense of 300 physical art-fair booths sustained by nothing but a Clif Bar than spend a day switching between browser tabs to look at photos and prices on a backlit screen inside the same two rooms that contains the rest of my life. I’m confident I’m not alone in that preference.

At the same time, what we really need to focus on is that this art-market A/B testing is a trap.

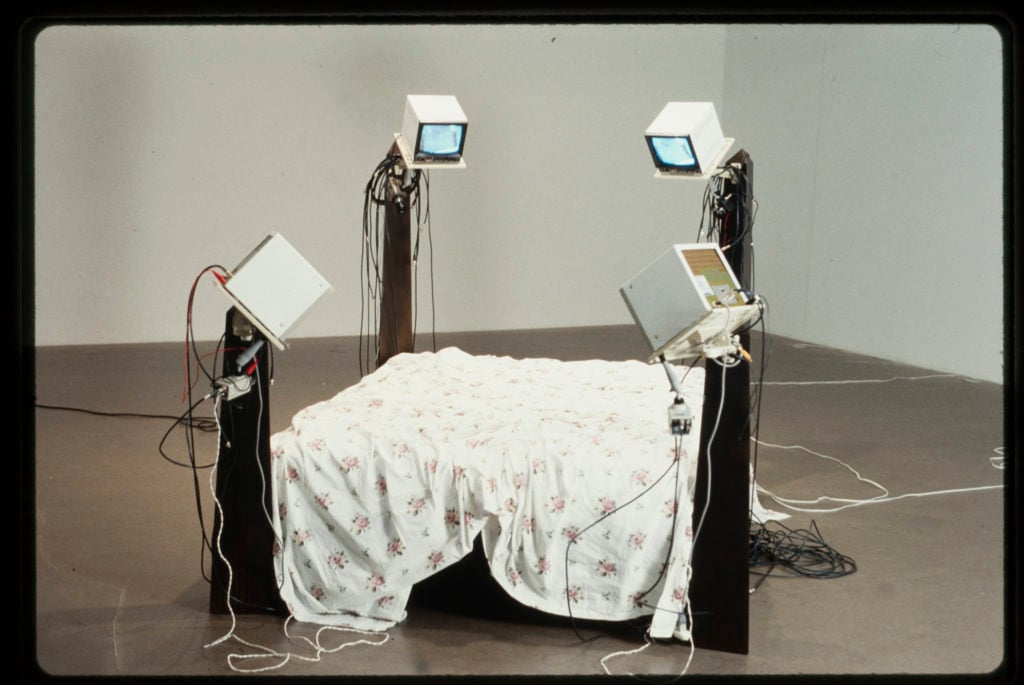

Always There (1994) from Scher’s Surveillance Beds. Courtesy Esther Schipper.

Riddle me this: Would you rather be required to swim a full lap around Manhattan every day in rose water, or in the signature blend of trash, biological rot, and toxic sludge mucking up the Hudson and East Rivers?

Obviously, the correct answer is rose water. But weighing those two choices blinds us to something more fundamental—namely, that it’s absurd to demand that someone swim a full lap around Manhattan every day! Changing the details doesn’t make the underlying premise any more reasonable.

All of the above loops back to the meat grinder of online art fairs. The common understanding in the Old Normal was that a big part of what made the art-market calendar so unforgiving was the nonstop travel. “Maybe if we could just transition some of these sales events online,” some people thought, “buyers and sellers could still do much of the same business—only more efficiently and more pleasantly.”

Well, guess what: the nonstop travel is gone… and most art-business professionals I know are basically just as exhausted and overextended as they were before.

In fact, there’s a sense in which the overwhelm feels worse. Just look at how many galleries are now supplementing their virtual fair booths with concurrent online sales platforms on their own websites. As of my writing, Gagosian (which was at the forefront of this trend) currently has a viewing room at Art Basel through June 24, plus a separate in-house viewing room in which the works being offered cycle every 48 hours for 10 days. Gladstone has its Art Basel viewing room, an expanded version on gladstonegallery.com that includes additional context and artworks, and a separate in-house viewing room dedicated entirely to watercolors by Ugo Rondinone, all open for business through June 26.

What does this mean? It means that the travel fatigue was just a detail, not the unreasonable premise itself.

Alex Prager, Speed Limit (2019). Photo courtesy of Lehmann Maupin.

In business analysis, it’s become popular to say that the shutdown is an accelerant. What’s been happening to varying degrees around the globe is exactly what would have happened without a lethal medical scourge. Great products would still have sold out. Dangerously over-leveraged companies would still have gone under. An appalling amount of taxpayer funds would still have been legally hijacked from the Americans most in need by the ones least in need. These outcomes are just taking mere weeks or months to materialize instead of years.

What doesn’t get discussed nearly as much is that the same acceleration is happening in our personal lives, too. If you were somewhat politically aware before, you’ve probably taken more direct action in the past few weeks or months than you did in the past several years. If you thought a dog might be a nice companion to have back in January, then since May you’ve probably been willing to fight a bare-knuckle boxing match for the opportunity to adopt a puppy. If your marriage was starting to buckle in the Old Normal, then the New Normal has either cracked it clean apart or left it barely holding together.

The reason is the same: the shutdown has drastically reduced our options for escaping essential questions. Just like an increasingly restless couple used to be able to distract themselves from their base-level incompatibility by meeting up with mutual friends at their favorite bar for a night, art-fair participants used to be able to distract themselves from the calendar’s unsustainable pace by escaping the convention center for an evening to see a great museum show—or even by tacking on a short vacation to a nearby destination at the end of a grueling week.

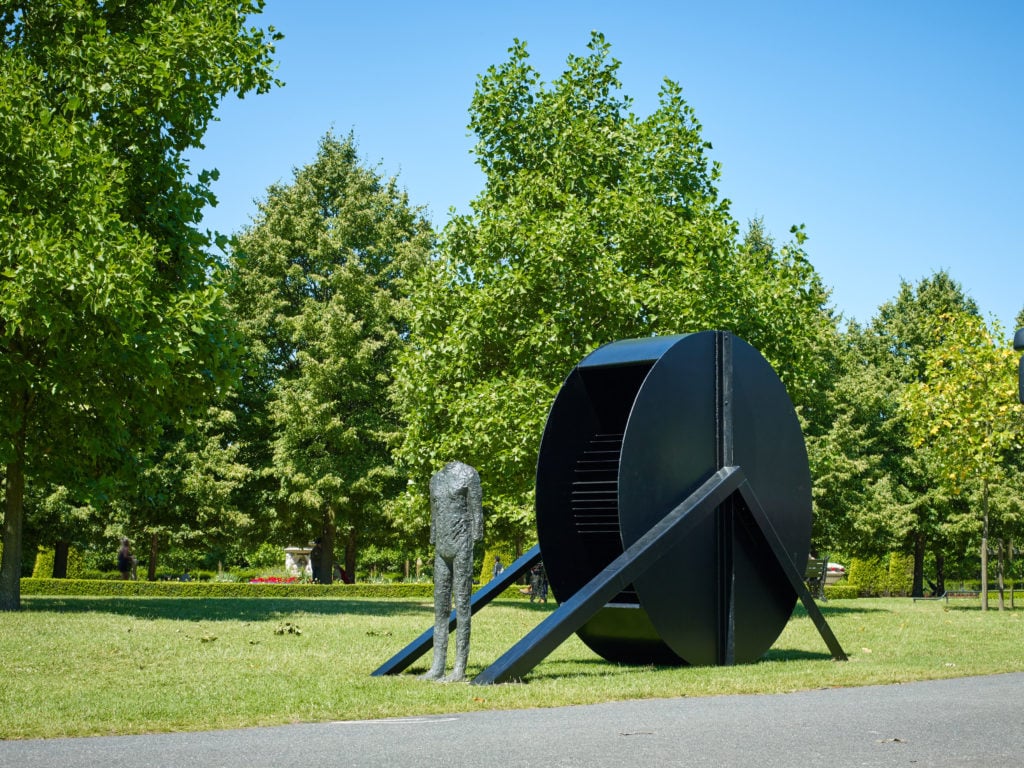

Those opportunities have vanished in the New Normal. What’s left is just the hamster wheel in its most stripped-down form.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Standing Figure with Wheel (1990). Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art. Photo: Stephen White.

As a smart dealer I talked to this week pointed out, the effect is amplified by the fact that the entire art fair is now being channeled through the same access point: the screen. For example, if an exhibitor didn’t care about the fair’s program of panel discussions before, the venue for the talks was so far removed from the trading floor that they could easily forget it even existed.

Now that the schedule and the events are being broadcast through the same digital interface as the parts of the event that actually concerns them, though, they found themselves asking… Wait, why does the fair need to do these again? And why are my booth fees subsidizing the cost?

The questions only get more urgent when the same device mediates not just the entire art fair, not just the entire art market, not just (nearly) your entire profession, but also most of your personal life. Line up so many components next to each other in one repository like this, and you start finding out what has value to you—and what doesn’t—even if you didn’t particularly want to. And the answers may scare you.

Look, I might be in the minority here, or at the very least being swayed by conversations happening in an echo chamber. I just think that if we believe that we can meaningfully ease the punishing demands of the 21st century art market simply by rebalancing the proportion of online versus offline events, we’re kidding ourselves.

More and more of the art world is inching out of lockdown every week. Galleries in New York were permitted to reopen by appointment last Monday, and a group of dealers in Berlin installed actual gallery shows of the works they were presenting on Art Basel’s sales platform. Although legitimate fears of a public-health relapse loom (setting aside that the US’s curve has plateaued, not flattened), the Old Normal hasn’t felt so reachable in months.

Regardless of when the shutdown finally ends for good, let’s see how many of the industry’s decision-makers exit it agreeing that more dramatic changes are needed to make the annual calendar sustainable—and more importantly, what they decide to do about it.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: When you’re sheltering in place, there’s nowhere to hide from hard truths.