Opinion

Kenny Schachter on Learning to Love the LA Art Scene (Except Those Wacky Private Museums)

The laid-back town was no match for our nervy, amped-up columnist.

The laid-back town was no match for our nervy, amped-up columnist.

Kenny Schachter

I am all but Los Angeles illiterate—I have only been to the city twice, for a handful of days. I don’t go to movies, or even watch them on laptops or planes. As an overweight, stuttering child from the suburbs of New York who couldn’t publicly pronounce the letter ‘D’ (now I can’t/won’t shut up), I never found LA a particularly attractive proposition, despite my romance of car culture. So when I recently took a trip to Tinseltown to curate a summer group show at Ibid Gallery (featuring my wife and four children), it was with a certain degree of trepidation.

Los Angeles is a weird place. Angelenos, I observed, have a messianic otherness about them, self-consciously calling attention to themselves and their city in the third person. There’s a refrain heard over and over again: This is so LA. It reminded me of Carly Simon’s song “You’re So Vain.” Also, even though there are more monster private museums and galleries bursting onto the scene than diet crazes, there are not a ton of indigenous culture vultures (of the collecting variety, anyway).

Similar to London, LA is obviously spread far and wide geographically, though the pace of the city is unhurried and languid, with the ever-present traffic a low din in the background (they don’t honk). The driving is incredibly tedious—for a car nut, no less. You lose days, and could go broke without wheels of your own, of which I had none. I think they issue traffic summonses for attempting to walk. Like a five-year-old, five minutes into each ride I noticed myself asking: How much longer? When an Uber driver inquired if I knew directions, ignoring the satnav suction-cupped to his dashboard, I began to quiver, as I am pathologically fearful of getting lost.

Every morning, as a result, my hotel resembled a Situation Room where I systematically mapped out itineraries for visits to museums, galleries, studios, etc. Surprisingly, for anyone who knows them, my kids turned up for ninety-eight percent of these jaunts.

What did we find? Well, forget what I said about LA’s laid-back vibe. We encountered such severe sniping, and such ruthless roasting of fellow artists, collectors, dealers, and curators, that it was eyebrow-raising even for the art world—seemingly worse than what you find in other art-centric cities. I ascribed this to the concentrated size of the tiny art scene, made up of a circle of insiders with a much smaller circumference than in New York—but growing exponentially. At the same time, LA was inspiring and uplifting, and I actually liked the place. (Sounds like I am ready to join the sect.) But fear not, there was still plenty to moan about.

An exterior view of the Broad Museum. Photo by FG/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images.

If a museum were to have an improbable one-night stand with Minnie Mouse, their illegitimate offspring would take the form of LA’s private foundations, theme parks for adults. Sheepishly, I admit skipping the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art (this time) in favor of the Broad, Paul and Maurice’s Marciano Art Foundation, and the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation (the sleeper of the three). I am still trying to determine if the Marciano brothers retain ownership of the underlying collection and, along with it, the capacity to privately transact. I get the feeling these hybrid institutions eat up the natural audience painstakingly built by the local museums (as well as their future art donors) in a zero-sum game of one-upmanship.

Though they obviously add to the overall fabric of the city, perhaps these foundations make more sense in China, where there’s just one contemporary art museum (at present). The curatorial voice of these upstarts reads more like a vibe, dictated by the founder’s fancies and follies (or those of their advisors) and what was recently on offer at the Basels and at auction. I am not judging whether art without scholarship is inherently good or bad—rather, they’re a bit of a ‘tweener, caught between institution and fun house. They all undoubtedly have something to offer; precisely what, history will tell.

The Broad’s collection has been well-reviewed, including the fact that you can’t get into Kusama’s Infinity Light Room unless you reserve well in advance, since a ticket is harder to come by than a trendy restaurant reservation. (Of course, one of my kids tried to bum rush the bewildered elderly security guard.) Going up the claustrophobic escalator feels akin to Matthew Barney writhing in a Vaseline tube for Cremaster 11 (or whichever).

The experience in these foundations is a box-ticking exercise of the rich and famous of international contemporary artists. There are Wools and Wades aplenty, and you can get lost in all the Ligons; Oehlens outnumber any number of others. Add to that Grotjahns, Bradfords, Mehretus, Rubys, and (Jonas) Woods—the lists go on, dizzyingly.

Jeff Koons’s tulips sculpture at the Broad. Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images.

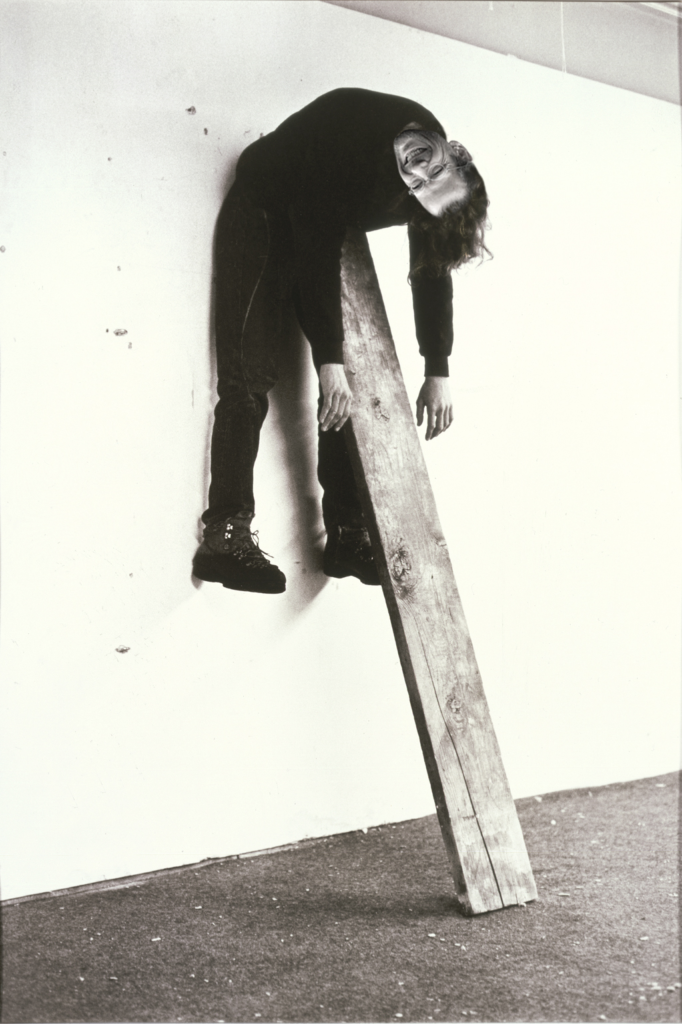

How many artists overlap between the city’s museums, public and private? A lot more than there are hardcore collectors in LA. The profusion of showpieces by Koons and Basquiat recalls the trophy room in a big-game hunter’s lodge, and some were even less lively. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Jeff Koons’s cluster of tulips resembles a bouquet of buttholes. I began to feel like Charles Ray in Plank II from 1973, his epic of apathy in the Broad collection, with the artist’s body slung over a two-by-four propped up against the wall in traditional LA minimalist style, listless and dead.

The logo of the Guess clothing company, where the Marciano fortune was made, resembles an upside-down symbol from the Scottish Rite Masonic Temple that houses their collection—at the suggestion, it turns out, of artist Alex Israel (according to Wikipedia, funny enough). How fitting for LA. Maybe the whole enterprise is an offshoot of the Illuminati—but I’m beginning to sound like Oliver Stone. The architect is Kulapat Yantrasast, also the designer of David Kordansky and Ibid’s galleries, the Anabelle Selldorf of LA (but, to me, better). Meanwhile, the salesman in the bookstore pointed to the “inherent spirituality” of the refurbed temple, calling it better than the Broad and adding that “no one ever accused us of vanity, unlike that other foundation.” He’s really mastered his Om.

Everywhere you go, the elephants in the room are Stefan Simchowitz and what happened to Paul Schimmel (more to follow). When my kids went to the barber, the hairdresser mentioned how much she couldn’t tolerate Simco. I was going to ask the Uber driver his opinion. Before I flew to LA, Simchowitz called me and tried to spin the commercial interconnections of the Marcianos, their steady stream of advisors, and the relatively small number of galleries that bore the fruits. Had they bought anything from him, of course, he’d have been effusive and called the Marcianos the new yardstick for collecting.

Speaking of which (unsarcastically), the Weisman Art Foundation was my pick of the week, a gem of quirkiness and eccentricity installed in a mansion in the Holmby Hills (wherever that is) that reminded me of a Modernist version of Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. A hoarder’s paradise, in other words. There, you will find Brancusi, Picasso, Still, Rothko, de Kooning, Rauschenberg, and Judd cheek-by-jowl with more commercial (read: trite) offerings, all in a residential setting untouched since the days when people last lived there in the ’90s. I’d say it was so LA it was like a movie set, but I won’t succumb. When I pulled up to the estate (and it is no less) I was met by a small group of patrons and a docent who declared: “Hello, I am your tour guide, and an art advisor.” The art-dealing docent! Who could invent?

David Kordansky Gallery, exterior view, corner of La Brea Avenue and Edgewood Place. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

After previously falling out with gallerist David Kordansky (over a past column), I achieved a détente by breaking macrobiotic bread at his local vegan. He ordered both still and sparkling, a water spritzer. In a city that launched the concept, the menus allowed no substitutions. Kordansky hails from the East Coast but stayed West after studying to be an artist (like so many dealers before him), and has made his mark as a commercial force in the new generation of dealers, post-Blum & Poe. David is a didact in the best sense of the term, sometimes more convincing than others but always sincere in his intent; hats off to his West Coast success story. I look forward to continuing the dialogue.

Dull (architecturally) and uneventful Downtown LA is the latest gallery enclave. There you will find Adam Lindemann’s Venus Over Los Angeles and Nicodim, owned by the formerly homeless Romanian Mihai Nicodim. I previously jibed the painter Razvan Boaz, on view at Nicodim, due to the fact his paintings looked like Sigmar Polke-ettes. He’s evolved since then and added to the mix romantic and mannerist semi-nudes. Nicodim represents fellow Romanian phenom Adrian Ghenie. Lindemann extended a courteous neighborly hand with an invitation to his show entitled “Cunt”; he’s currently planning a residential development project there, a fact not widely reported outside of LA property journals. From the looks of things, he’ll make a killing.

Exterior of Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Photo: courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

For my tastes, Hauser & Wirth tries too hard to not try, leaving so many remnants of its industrial building’s earlier incarnation coupled with the darkness of the exposed wood beams. The much-lauded food at the gallery restaurant was too rich; for some reason my lettuce and avocado, the last two things that need cooking, came grilled. The egg-laying chicken in the attached coop was said to be depressed, even though she was facing no impending doom other than the relentless LA sun. I’m no white-cube proponent, but I found Hauser a bit too rustic, heavy on wood and old factory fittings. It was designed by Annabelle Selldorf.

Beyond the physical space, the most dogged, unremitting chatter of my LA week was what ever happened to Paul Schimmel, the latest former museum curator to cross into the dark side of gallerydom, taking a Hauser partnership, and then getting popped back out. Rumors were swirling to the extent that it amounted to a local pastime, and they ranged from sordid (don’t ask) to sanguine. He spent too much, fought with Jason Rhoades’s widow, couldn’t/wouldn’t sell—many theories are making the rounds. Probably none are true, but who knows; I hear there’s a lawsuit or two fermenting, though. (Is that more organic than brewing?)

The owner of Ibid Gallery is Magnus Edensvard, an unassuming Swede, sweet as pie, unless you want to do something he isn’t keen about. He’s got a point, most of the time. He’s been in the press recently since his relinquishment of his London gallery, principally as a representative of all the mid-market galleries under duress that are being forced to adopt new models—but the fact is he simply picked up sticks, moved to LA, got married, and had a very cute baby. When he asked me to curate the summer show, I naturally conscripted my family and came up with “Nuclear Family,” a farrago of me and my family (Adrian, Kai, Gabriel, Sage and wife, Ilona) and the artists who formed a formidable part of our lives: Vito Acconci, Paul Thek, Zaha Hadid, Rachel Harrison, Sigmar Polke, and Joe Bradley.

The Schachters install. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

There was a (small) handful of demonstrators on hand for the opening to protest Ibid as an agent of gentrification—they call it “artwashing”—in the largely non-residential, industrial area known as Boyle Heights; one of the demonstrators, I was told, is known to have resided in the area for less time than most of the galleries there have. My kids found the ruckus a prime selfie opp, and somehow the anemic demonstration made it into the Guardian in the UK and Page 6 of the New York Post. Don’t tell them about Adam’s development.

My editor didn’t want an infomercial, so I will keep my proud gushing about “Nuclear Family” and my precocious clan to a minimum. Okay, so I’m the Simon Cowell of the art world, a Svengali nurturing the next One Generation (trying, anyway)! Are you aware of the Boyle Family, the Scottish art collaborative that made art together until the dad’s death in 2005? That’s us, but we each have our own territory. Another Uber driver actually asked if I was the manager of a boy band, glancing at the interactions of the kids (my wife, Ilona, couldn’t come because of a visa issue), such was the camaraderie. My next show will be called “Art Band.” By the end of the first full day’s proceedings, nearly all of my kids’ art had sold out (including to Lindemann, angling to make another killing). I had a hunch that would be the case, so Magnus shouldn’t have worried. In fact, he might consider adding one or another to his gallery roster.

A piece by Calvin Markus. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

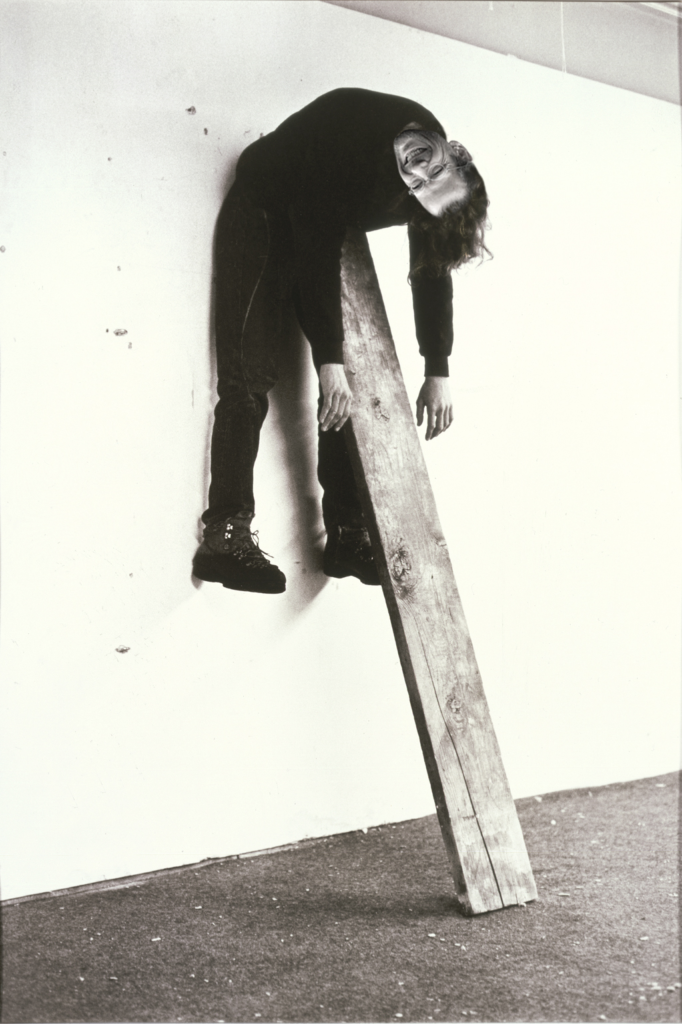

Without full disclosure of the extent of my crew, I ambushed the studio of Calvin Marcus with all four of my kids in tow (as I always do), and he couldn’t have been more gracious and kind. Shy of 30, with success out of the gate, the artist was understandably a little cagey and cautious in his demeanor, too: we live in fickle times, with capricious consumers of contemporary art. He first came to acclaim carving demonic faces into the breasts of ceramic chicken carcasses and affixing them to canvases, the whole composition painted in the green of a video screen.

Marcus’s is a media-savvy vision for the digital day: a contentless void—or a canvas painted to replicate one, at least. The devil chickens are a nod to the longstanding Californian tradition of ceramics championed by such practitioners as Peter Voulkos, Ken Price, and Ron Nagle (who wrote music for Barbra Streisand and won an Oscar for sounds effects for the Exorcist).

A painting by Aaron Garber Maikovska. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

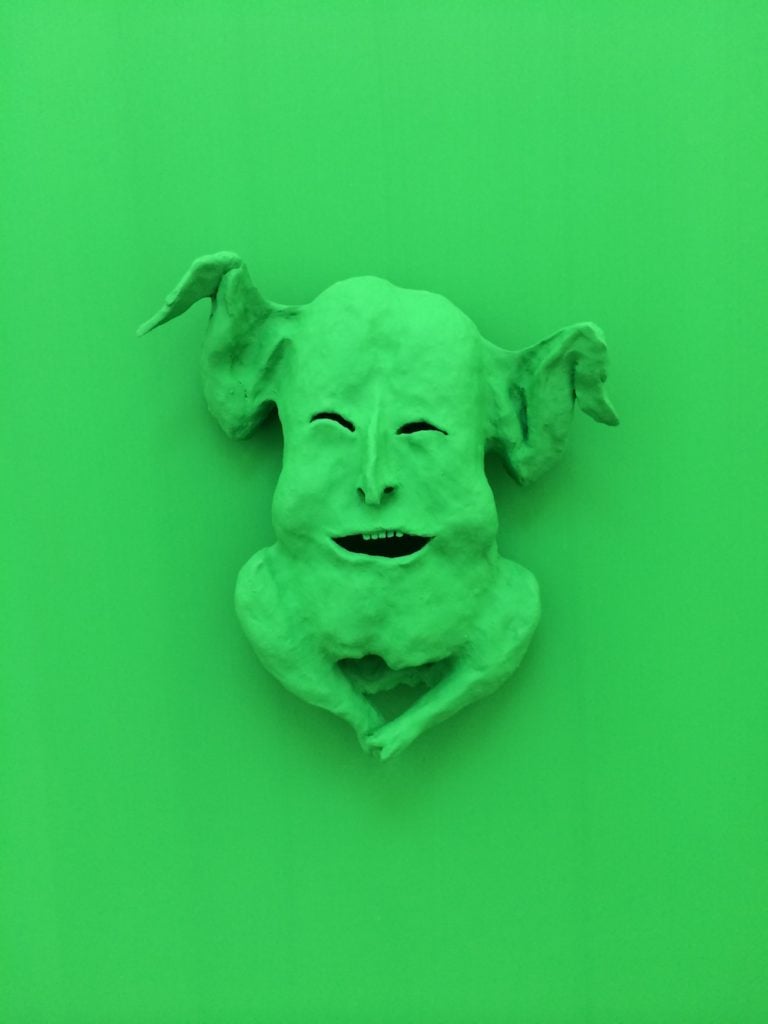

We also stopped by the studio of Aaron Garber Maikovska, who makes videos where he is the sole player, interacting with constructed elements in the landscape in a wild, herky-jerky, improvisational manner that brought to mind the free-form interpretive dance of a possessed Led Zeppelin fan. Disconcertingly so, at times. Again, a market darling, Maikovska’s manic, all-over scribbles in colored paints and oil stick on gator board resemble the efforts of a child home alone (another movie reference!), with a nagging case of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and too few (or far too many) of their meds. The standout performances have the absurdity of John Cage farting out indecipherable sounds on stage; I tried to stifle laughter in the audience.

Giacometti palms. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Driving through what feels like multiple states, navigating LA requires a degree of patience I’m not exactly equipped with. Though Angelenos go to great lengths to seem chilled out, I suspect it could come down to another case of the city’s famous acting. According to my kids, LA is a youth-oriented town, and, with such solipsism, it would have to be. It reminded me of Miami on steroids. But there could be serious potential for its art scene, once you get past the lava-like pace; at the Ibid opening, I met a collector who was a fan of Paul Thek and on the lookout for a work—and a fan of my writing, to boot. (Can’t be that bad a place!) For a Londoner like me (for the last 13 years), LA is remote—when you awaken, the rest of Europe is winding down. But working under giant Giacometti-proportioned palm trees for the week wasn’t so bad.

The schools, artists, museums, foundations, and collector-enthusiasts that populate the LA landscape today are a testament to a city of its time and beyond. And yes, LA is a little like a cult; in fact, I might enroll in the next level of indoctrination. For “Nuclear Family,” I curated art from the house of my heart and from the heart of my house, literally stealing work from the bedroom and dining-room walls. Checking out of town, I got repeatedly reprimanded by security at the airport who were yelling at me to pull up my track pants. Maybe the city’s youth-cult vibe rubbed off on me. Worse things have happened!