Opinion

Kenny Schachter Is Back, Baby! And He’s So OVR It. (But Has Plenty to Say About the Ron Perelman Selloff)

Our columnist rides again, with some choice thoughts on the uncanny new reality of New York's fall art season.

Our columnist rides again, with some choice thoughts on the uncanny new reality of New York's fall art season.

Kenny Schachter

I hope this article finds you and your family safe in these strange and unprecedented times. No, this is not yet another entreaty to visit an Online Viewing Room (OVR)—or, in my case, an OOPS (One Outstanding Person Show, on www.KennySchachter.art). Actually, I’ll admit I’ve neglected to visit a single OVR, or digital fair for that matter. My reasoning is that anything worthwhile will filter its way to Instagram, saving me the effort of wasting my time wading through the morass of digital static. After covering (and participating) in fairs for 30 years, however, I’m relieved that they have all come to a grinding halt—except for the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, the only London fair that fared as an in-person event during this year’s so-called Frieze Week, and which I hear was great.

Hopefully we’ll be able to return to a sense of normalcy sometime relatively soon—unless, of course, there’s a holdover tenant in the White House after November 3rd, in which case ignore the entirety of this column and… run! I appreciate that the loss of revenue from going fairless is near-crippling for galleries across the globe, but an upside could rise from the ashes that replaces incessant, attention-span-killing booth-hoping as the primary (and often only) means by which we experience and consume art; namely, the rekindled art of going to galleries. Harkening back to a less chaotic and congested time—before we all became too petrified to miss a single fair, no matter where—a new post-FOMO world has blossomed.

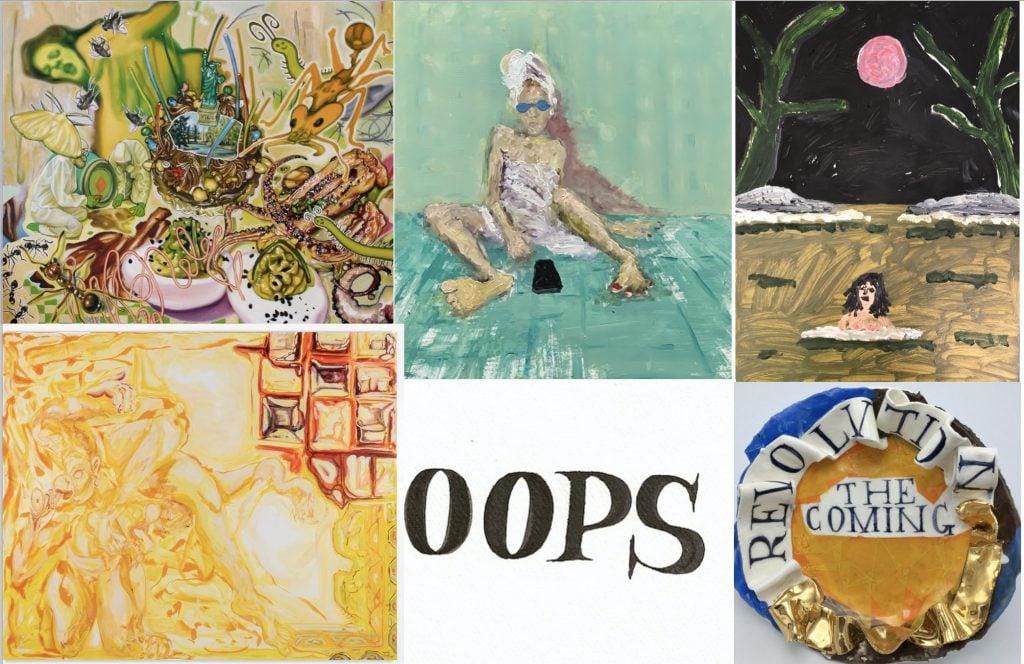

Forget OVR (Online Viewing Rooms) when there’s an OOPS (One Outstanding Person Show) on the way. From left to right, top to bottom: Charlotte Fox, Eva Beresin, Tom Rees, Josephine Messer, Ruan Hoffman. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Amazingly, the shutdown has both reinvigorated and instilled a new urgency in local gallery scenes and accelerated the inculcation of experiencing art online. Granted, nothing online can or will (for now) replace seeing art and art people IRL (yes, I miss the community, really, though mostly that of the other workabees), but Instagram and the other platforms are great tools nonetheless. Scott Reyburn, the perennial prognosticator of market gloom and doom, wrote that “up to a third of galleries are expected to fold, with smaller ones particularly vulnerable. The shift to online auctions has seen an equally dramatic slump in secondary-market revenues at [auction houses].” Going even further, William Goetzmann, the Yale finance grandee and co-author of the 2014 study The Economics of Aesthetics and Three Centuries of Art Price Records, prophesied that not only will small and mid-level galleries fail, but, with them, the entire culture around art and collecting. With all due respect, what a load of bullshit.

As I never tire of saying, art has been voraciously coveted since it first came off the walls of caves, and nothing short of nuclear conflagration (or Trumpian Armageddon) will change that. Ever. By the way, the business model of small-to-mid-level galleries (SMLs, pronounced “smells”) was flawed from the get-go: you sell art to make money, but keep it to create wealth. They only survive because it’s precisely the artworks at the lowest price rung—the ones handled by SMLs—that people feel most comfortable snapping up as impulse buys in uncertain times, if only for the feel good/dopamine factor. Art is Teflon, up 10 to 20 percent one cycle, down the next, but always back just as quickly, and often beyond. That will never change. But if SMLs want to do more than just get by, they’ll need to buy (their own artists).

An important message for America. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Besides Instagram and OVR, plenty of other fundamental changes are afoot in the reconstruction of the art industry, a world more conservative than any I’ve ever worked in—including the stock market, law, and fashion—and that says a lot. There’s the burgeoning business of experiential art, most notably Pace’s Superblue, as part of the ongoing Disneyfication of the art-going enterprise. I suppose there’s a place for this stuff—but it still needs to be art, and I’m not so convinced at this stage that it is. Hauser & Wirth appointed Ewan Venters, previously of the upmarket London department store Fortnum & Mason, as the mega-gallery’s first global CEO as it continues its evolution into a fully-fledged lifestyle/hospitality company. Who knows, they might even serve H&W-branded caviar at their forthcoming bar/restaurant/hotel at the former Audley pub in London’s Mayfair neighborhood.

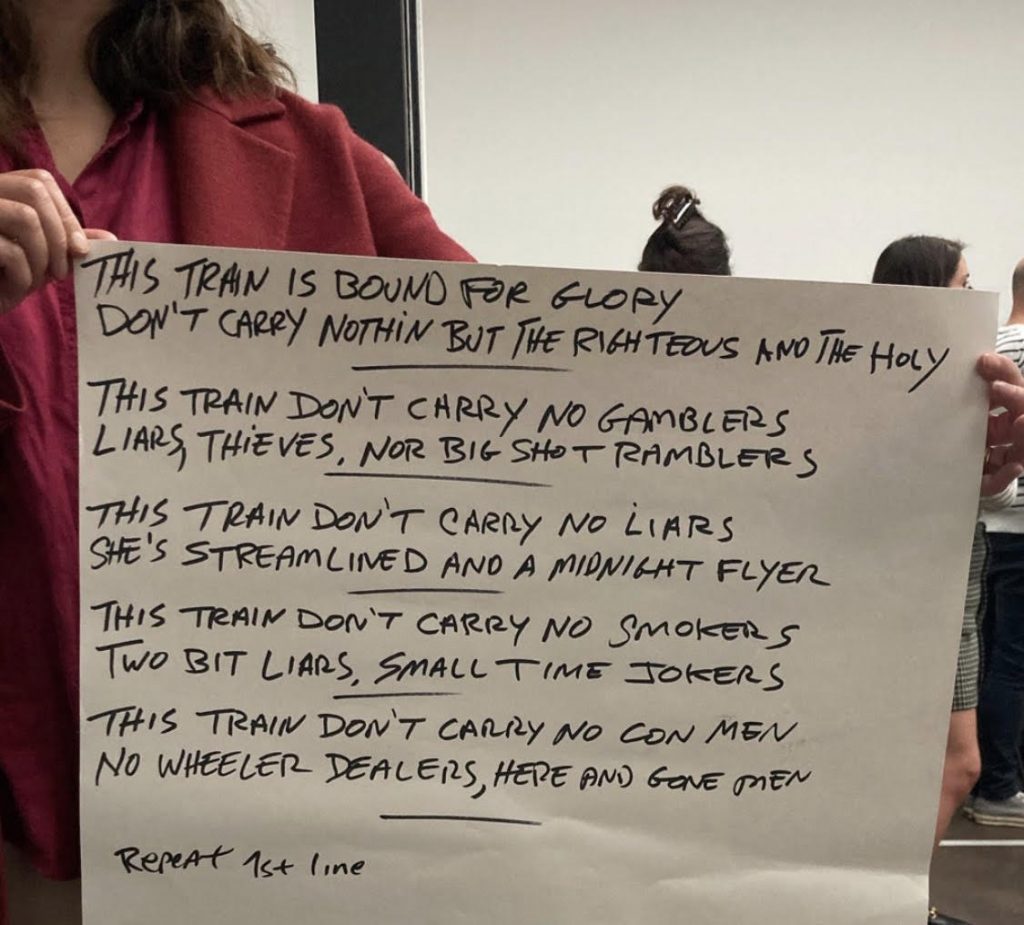

Gogo has launched Gagosian Premieres, putting artists and celebrities (ugh) in conversation in lieu of the fizzy gallery openings made impossible by the ongoing social-distancing era. The prognosis? Well, the first matchup of Mary Weatherford’s paintings as a backdrop for Thurston Moore singing “This Train Is Bound for Glory” (popularized by Woody Guthrie) is an odd choice, featuring such lyrics as: “This train don’t carry no two-bit liars, thieves, conmen, wheeler-dealers, gamblers….” That pretty much rules out the entire art world!

Looking every day of his 62 years, Thurston Moore needed some help with the lyrics in his premier performance on Gagosian Premeiers. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

As for online art auctions, the most unforeseen aspect is the size of the (captive) audience they’ve garnered as our hunger for content takes us to ever more astonishing heights, as evidenced by the 280,000 people that tuned into Christie’s sale last week, which was more notable for flogging a set of old bones than art. With the foreseeable end of live theater, movies, sporting events, and standup sets, the comedy of art auctions is all that’s left. This all smacks of “vicarious aspirational consumerism,” as Jeremy Hodkin of the the Canvas termed it. When most of us have no ready cash to spend, watching others indiscriminately dispense with it is apparently the next best thing. (Think of it as Twitch for the rich.) Voyeurism doesn’t do it for me, though—I’ll always hanker to hoard art. Speaking of which, don’t miss my second annual Hoarder sale at Sotheby’s in December.

Getting off on the conspicuous consumption of others as entertainment is pathetic enough. Much more shameful is the lack of people of color on the rostrums wielding phones or gavels, even as the houses are selling steadily increasing numbers of lots by black artists. I can’t recall a single black auction specialist in memory. That has to change and fast. Artist Anthea Hamilton recently staged an immersive installation as part of the Frieze-Week-That-Never-Was that consisted of commercially made black mannequins—at the very least, a few of those might have been employed as a stopgap measure to make the auction room look more inclusive. As is, it’s glaringly not.

As most of you know by now, my longtime source Deep Pockets, though an amalgam of a few characters, was primarily a dealer who is rather indisposed these days, but he’s been replaced by a new tipster—in these economically constrained times, let’s call her Cheap Pockets. And thankfully, she’s not at all parsimonious with her information. Ronald Perelman, amid well-publicized financial hardship caused by his crushing debt burden, has been selling pretty much all of his assets—including a boatload of art both privately and at auction—in the guise of economizing to a simpler life. I think the banks had more to do with these decisions than Perelman’s desire to downsize.

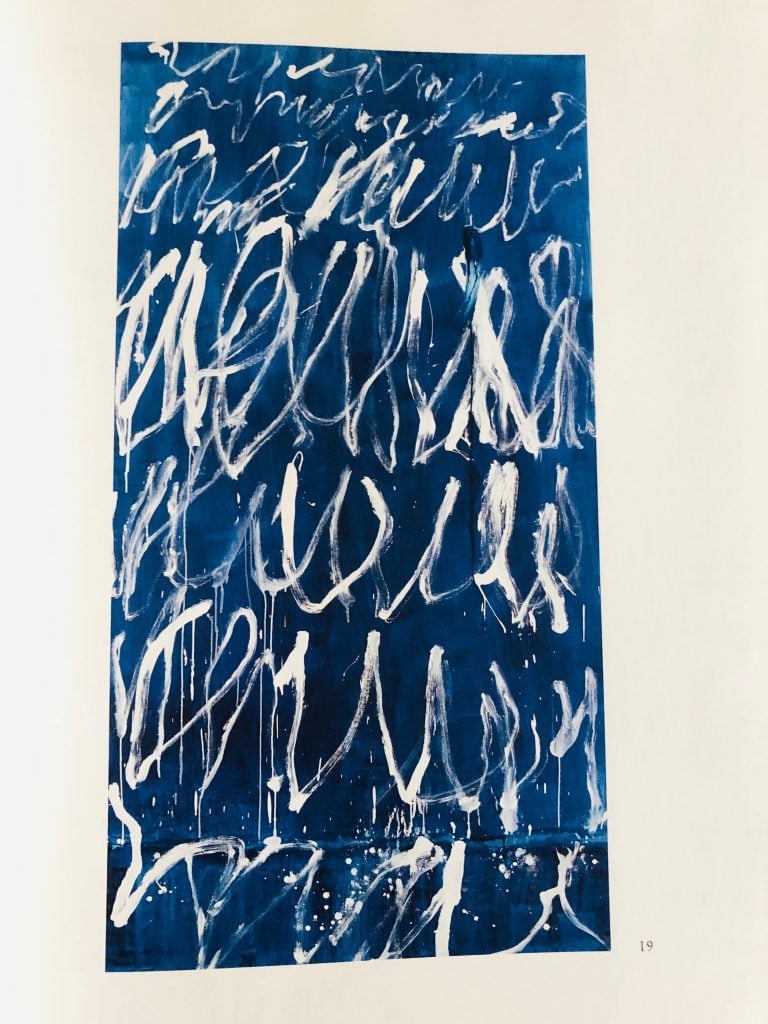

The Cy Twombly formerly owned by Ronald Perelman. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Sotheby’s and Christie’s have been drafted into action to sell off his trove, as has his previous courtroom foe, Larry G.—call it a marriage of inconvenience. Cheap Pockets told me that Sotheby’s private treaty was responsible for the sale of Perelman’s Jasper Johns painting, 0 Through 9, to David Geffen, who apparently loves nothing more than feeding off the blood of the fallen (especially someone he is said to dislike as much as Perelman), with Larry’s approbation, which Geffen allegedly had to pay for. (There’s no such thing as a free lunch in the art world, not even visiting experiential art galleries.)

That Geffen was the buyer I admit at this stage is unconfirmed—and I went begging to a bushel of billionaires in search of the answer—but not the fact that the asking price was $75 million before selling for $73.5 million, with Perelman pocketing about $70 million of that. Gagosian apparently singlehandedly sold Perelman’s blue Cy Twombly for around $20 million. So said the art whisperer, at least. (The touted participants, however, said otherwise: Gagosian denied the Twombly sale, Geffen denied the Johns purchase, and Perelman did not respond to requests for comment by press time.)

To wrap up the fate of Perelman’s former art stash, Christie’s may have sold Perelman’s Twombly Bolsena at the last minute on the low estimate to the perennially bargain-hunting Nahmads. (The Nahmads had no comment.) And Gerhard Richter’s twin candles went to the auction world’s brilliant go-to Taiwanese mega-collector/guarantor with steel cojones, Pierre Chen, who was also offered the Johns.

Can you draw a picture of what $73.5 million looks like? Jasper Johns’ 1961 painting 0 Through 9. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

A few more juicy tidbits before I let you go. White-hot painter Robert Nava, who graduated from Yale’s vaunted MFA program—where he learned how to paint badly (in the best way; I own a work)—will ultimately go to Pace, and there’s a good chance another well-documented market darling by the name of Amoako Boafo will land at Gagosian. No matter how you slice it, Gagosian is a genius the likes of which we haven’t seen since the dealer Joseph Duveen (1869–1939), and though he won’t be knighted, made a Baronet, and ultimately elevated to a peerage as 1st Baron Duveen was, there won’t be another like him anytime soon. And someday you’ll miss him. Oh, and Jay-Z bought a Barkley Hendricks painting for between $15 million to $20 million. (Music legend Jimmy Iovine, meanwhile, snapped up his own for around $10 million.)

Back in London, Phoebe Saatchi Yates opened a gallery (with her husband), steadfastly maintaining that what’s left of her dad Charles’s art collection won’t become fodder for her secondary-market dealings. That’s an auspicious start for the latest in an art-dealing dynasty—launching on what I can only imagine will prove a falsehood over time. She’ll fit right in! Not dissimilarly, Damien Hirst, when he began his Newport Street Gallery non-for-profit private museum, mentioned he’d never show his own art. That was before his present exhibition “End of a Century,” featuring more than fifty works spanning Hirst’s career from the 1980s to the ’90s. When you visit you might want to bring along a Carbon-14 dating kit to determine if some of the art may have only just recently come off the assembly line. (Which is what I’ve heard, anyway.) Also bring a checkbook, as I’m sure no decent offer will be denied.

I’ve never seen so many “For Rent” signs as I have in the past six months in NYC—and, in the short time I’ve lived here, there has been a marked increase in homelessness on the city streets. Some additional COVID collateral damage is the disastrous rash of museum deaccessioning. I only hope it all stops soon. But throughout, the art world (and market) remains miraculously strong. I haven’t noticed any visible decline in the thriving New York gallery scene, which appears to be in rude health at the start of the fall season, at least from the sheer amount of activity. Thirty years ago I got into art to run away from business, and then art became bigger than the big business I fled. The song remains (exactly) the same.