Archaeology & History

Researchers in Israel Are Using A.I. to Translate Fragments of Ancient Cuneiform Text Into English

The researchers are calling it a major step in the preservation of the cultural heritage of Mesopotamia.

The researchers are calling it a major step in the preservation of the cultural heritage of Mesopotamia.

Artnet News

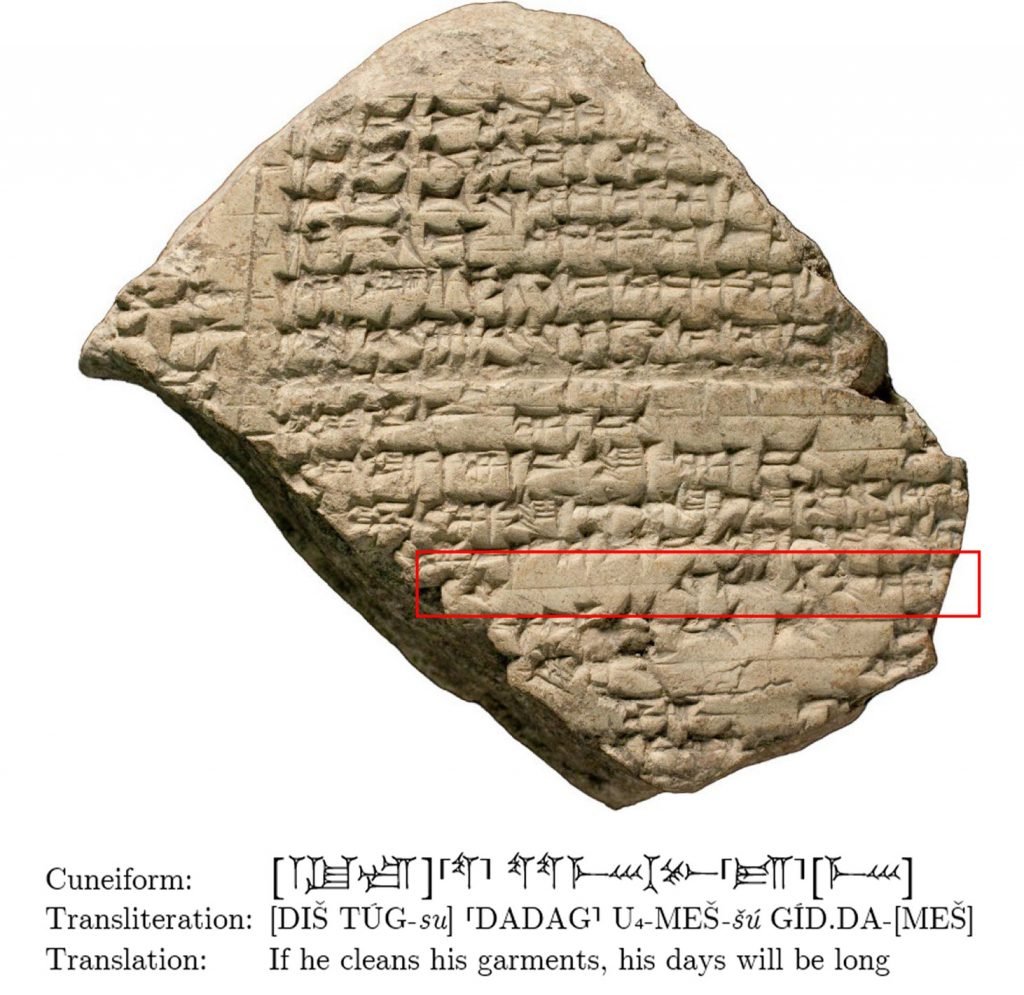

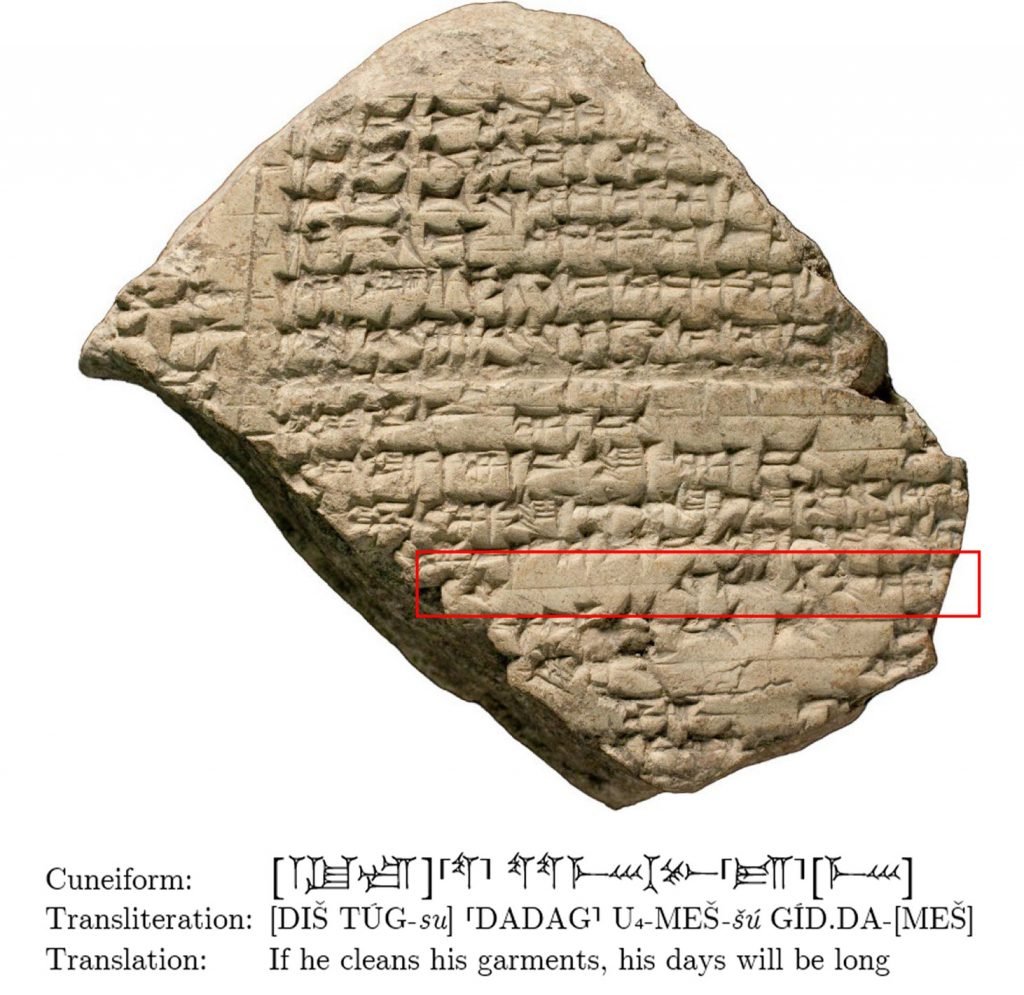

Scholars at Tel Aviv University and Ariel University, in Israel, have used artificial intelligence to translate fragments of ancient cuneiform texts on stone tablets into English with what they say is a high degree of accuracy. They call the project “another major step toward the preservation and dissemination of the cultural heritage of ancient Mesopotamia.”

The scholars presented the first neural machine translation from Akkadian into English in the May issue of PNAS Nexus. Their results are “on par with those produced by an average machine translation from one modern language to another,” noted Arkeonews.

In the last 200 years, archaeologists have found hundreds of thousands of texts that tell the history of ancient Mesopotamia, most of them written in Sumerian or Akkadian, explained the authors. But most remain untranslated because of their vast quantity and the small number of experts who can read them, as well as the fact that most of the texts are fragmentary. Furthermore, cuneiform signs are polyvalent, there are many different kinds of texts, and even the names of people and places can be written as complex sentences.

“First, let me state that we believe that A.I. will not replace philological work,” said Luis Sáenz, of the Digital Pasts Lab in the Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology at Ariel University, one of the authors, in an email to Artnet News. “We want to speed up the process. Our hope is that A.I. will eventually be able to help both Assyriologists and non-Assyriologists read cuneiform texts in the future.”

This is just the latest example of scientists using the newest tools to work with the oldest materials. University of Kentucky researchers developed an A.I. system to read scrolls that were incinerated when Mount Vesuvius erupted in the year 79, and archaeologists in Italy are working on a robot that uses A.I. to reconstruct ancient relics from their scattered shards.

“There are, of course, limitations to the model,” says Sáenz. “The lack of context makes ancient languages difficult to translate, since we only have fragments of texts. Fragments with only one or two lines are extremely difficult to work with for A.I. The future will require more tools to digitize data published in papers in order to keep training the model and to improve the results. Also, a user-friendly web-based platform for the public is important.”

More Trending Stories: