Within the art world—and, to a much larger extent, outside of it—2020 was one of the most tumultuous years in history. Museums and galleries faced financial challenges that threatened their very existence, as Black Lives Matter uprisings forced a reckoning with the art world’s structural racism and controversial monuments that celebrate shameful histories around the globe.

Here, we spotlight 12 thorny questions that sent shockwaves through the art world and sparked spirited debate that is sure to boil over into 2021.

Should Universities Teach Traditional Art History Surveys or Not?

Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Back in January—a much more innocent time for most of us—the year’s first controversy presaged many of the debates to come. Yale University announced it would eliminate its popular survey course, “Introduction to Art History: Renaissance to the Present,” as part of a broader overhaul to address concerns that its curriculum promoted a white, Westernized canon at the expense of other narratives. (New thematic courses—including “Art and Politics,” “Global Craft,” “The Silk Road,” and “Sacred Places”—would replace the standard 101 lineup.) The move struck a nerve with those who already felt cultural norms were changing more quickly than they could keep up with; New York Post labeled it “PC idiocy,” while the New Criterion likened Yale’s art-history department head to Joseph Stalin. The university, for its part, suggested the dust-up was largely a misunderstanding. In a statement, the department wrote: “Recent excitement on social media about Yale’s curriculum demonstrates just how significant and lively—even controversial—the study of art history can, and should, be.”

Why Did a Microsoft Ad Featuring Marina Abramović Spark a Right-Wing Satanic Conspiracy?

Promo image featuring Marina Abramovic wearing the HoloLens 2 headset Photo: Microsoft.

In the spring, a stranger-than-fiction clash entangled software behemoth Microsoft, world-famous performance artist Marina Abramović, and conspiracy theorists the world over. It all started when the tech company uploaded a promotional video for HoloLens2, a headset designed for mixed reality, that prominently featured the artist. Less than a week later, the ad vanished. In the interim, it turns out, it had been given a “thumbs down” by more than 24,000 users on YouTube. Many of the disapproving votes reportedly came after Infowars, a far-right blog run by Alex Jones, published a story attempting to connect the video to a bizarrely resilient theory—which stretches all the way back to 2016’s “Pizzagate”—that Abramović is a Satanist.

Confused? Artnet News critic Ben Davis went down the rabbit hole to unravel this controversy, and you can read about it in more detail here.

When Is It Okay For a Museum to Sell Art?

Christopher Bedford in Venice for “Mark Bradford: Tomorrow Is Another Day” at the US Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2017. Photo by Awakening/Getty Images.

When Artnet News spoke to Baltimore Museum director Christopher Bedford about the museum’s plan to sell several blue-chip works as part of its latest effort to diversify its holdings, he sounded more than confident about the decision. Though he stressed that the sell-off was not related to financial strain, he sought to take advantage of the fact that the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) had temporarily loosened its guidelines on how members could use the proceeds from deaccessioned art amid the pandemic.

He may not have expected just how emphatic the blowback would be. Weeks later, hours before a planned multimillion-dollar auction at Sotheby’s, the museum withdrew the works from the sale.

Other museums, including the Brooklyn Museum and the Everson Museum in Syracuse, forged ahead with deaccessioning efforts that took a more conservative approach to the new rules. But since the loosened guidelines remain in effect through April 2022, this is likely not the last time a museum will push the envelope when it comes to deaccessioning.

How Should We Reckon With Controversial Monuments?

A statue of Christopher Columbus at Grant Park in Chicago is removed early on July 24, 2020. (Photo by Derek R. Henkle / AFP via Getty Images)

As calls for social justice swept the country in June following the murder of George Floyd and other unarmed Black people, the long-simmering debate about controversial monuments leapt to the forefront of the national conversation. Outcomes were as wide-ranging as opinions about how to respond. In Richmond, roughly 1,000 protesters used ropes to topple an eight-foot-tall statue of Christopher Columbus, then proceeded to light it on fire and drag it to a nearby lake. In New York, the American Museum of Natural History ceded to demands to remove a monument to Theodore Roosevelt that had stood outside the building since 1940. In Chicago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot outlined a comprehensive plan to review the fates of the city’s most controversial public monuments following temporary removal of some. Meanwhile, across Europe, a groundswell of activism focused on toppling monuments to problematic figures from slavers to colonizers.

Will Leaders Change the Way They Treat Workers for Good?

Nathalie Bondil. Photo by Marco Campanozzi.

If pressure came to the museum boardroom last year, it came to the C-suite this year. As in other industries, activists and employees joined forces to call out allegedly abusive behavior in the workplace. Whether on Instagram or Twitter; in open letters; in the press; or in the offices of those with the power to hire and fire, workers aired their complaints. And in some cases, speaking up had a big impact. The director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit was fired; a top curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, as well as directors of the Akron Art Museum and the Cantor Arts Center, resigned; as did a board member at Rhizome who was unsatisfied with the New Museum’s response to reports of toxic leadership.

Some institutions hired outside counsel to investigate charges against top brass, including the director of the Detroit Institute of Arts and the chief curator of the Guggenheim (though not everyone was satisfied with the outcomes). Perhaps the messiest executive departure of them all took place in Montreal, where the former Montreal Museum director Nathalie Bondil was fired for (depending on whom you ask) fostering an unhealthy work environment or refusing to cede control to a newly hired curatorial director.

Why Was Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia Turned Back Into a Mosque?

Hagia Sophia, a former Greek Orthodox Christian cathedral, later an Ottoman mosque. Photo by Frank Bienewald/LightRocket via Getty Images.

It seemed no amount of alarm or vocal opposition could deter Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan from converting the world-famous Hagia Sophia, a UNESCO site, from a museum into an active mosque this past July. He transferred operations of the building from the Ministry of Culture to the state Religious Affairs Directorate—and less than two weeks later, announced that mosaics depicting Christian icons would be covered during Muslim prayer. It seemed to mark the beginning of a trend: At the end of August, the Turkish government announced it would also convert the Chora museum back to a mosque. Robert Ousterhout, a professor emeritus in art history at the University of Pennsylvania, called the move a “blatant attempt to erase Istanbul’s rich Byzantine heritage.”

Will Museums Make Good on the Promises They Made During the Black Lives Matter Demonstrations?

Outside the Brooklyn Museum during the Black Trans Lives Matter March in June 2020. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum Twitter.

After many museums responded to the Black Lives Matter uprisings sweeping the globe with messages of support over the summer, they were pressured to put their money where their mouths were. Well, first came the initial bumbling responses, like the Getty’s, which failed to mention George Floyd or Black lives; the Met’s, which used a work by Glenn Ligon in a post without his permission; or the Toledo Art Museum’s, which maintained the institution did “not have a political stance.” Some responses drew even more derision, like the Whitney Museum of Art’s (swiftly aborted) plan to present an exhibition of work purchased through charity benefits by predominantly Black artists at below-market prices. After these initial missteps, many museums pledged to take concrete action to address white supremacy in the form of staff trainings, inclusivity committees, and programming goals. But broader and more difficult questions—about how the business-as-usual at museums may undermine the aims they profess to be working toward—remain unanswered as we head into 2021.

Why Was There So Much Bad Public Art of Women in 2020?

Maggi Hambling, A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft (2020). Photo by Ioana Marinescu.

As outdated monuments come down, new ones honoring figures who have previously been pushed to the margins of history are going up. And the years after the #MeToo reckoning have resulted in some… very strange sculptures of women, including a number that ignited the commentariat in 2020. Artist Maggi Hambling set off a social media hate-storm for her depiction of feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft as a sexy nude figure emerging from an oddly shaped mound of silver.

Possibly even more painful to the eyes was the seven-foot-tall nude bronze Medusa statue—holding aloft the head of Perseus—installed outside of the criminal court in Lower Manhattan where Harvey Weinstein was tried. Critics took issue with the idealized figure—as well as the fact that it was the work of a male artist.

Should a Major Philip Guston Show Have Gone Ahead as Planned?

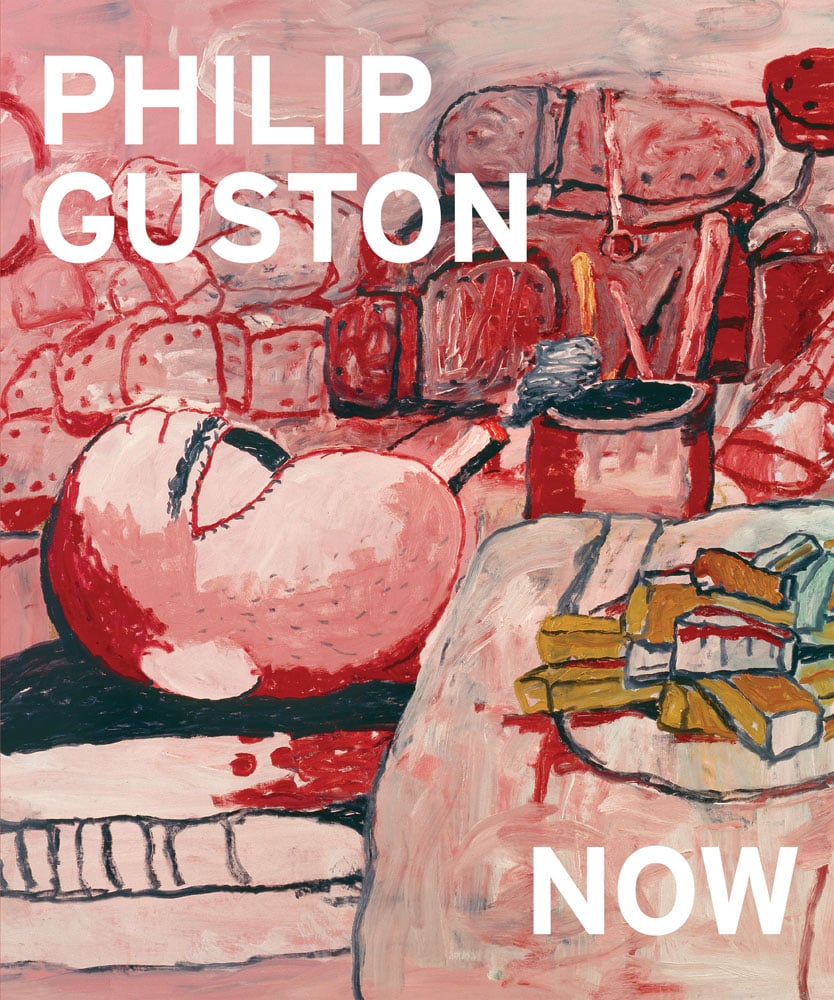

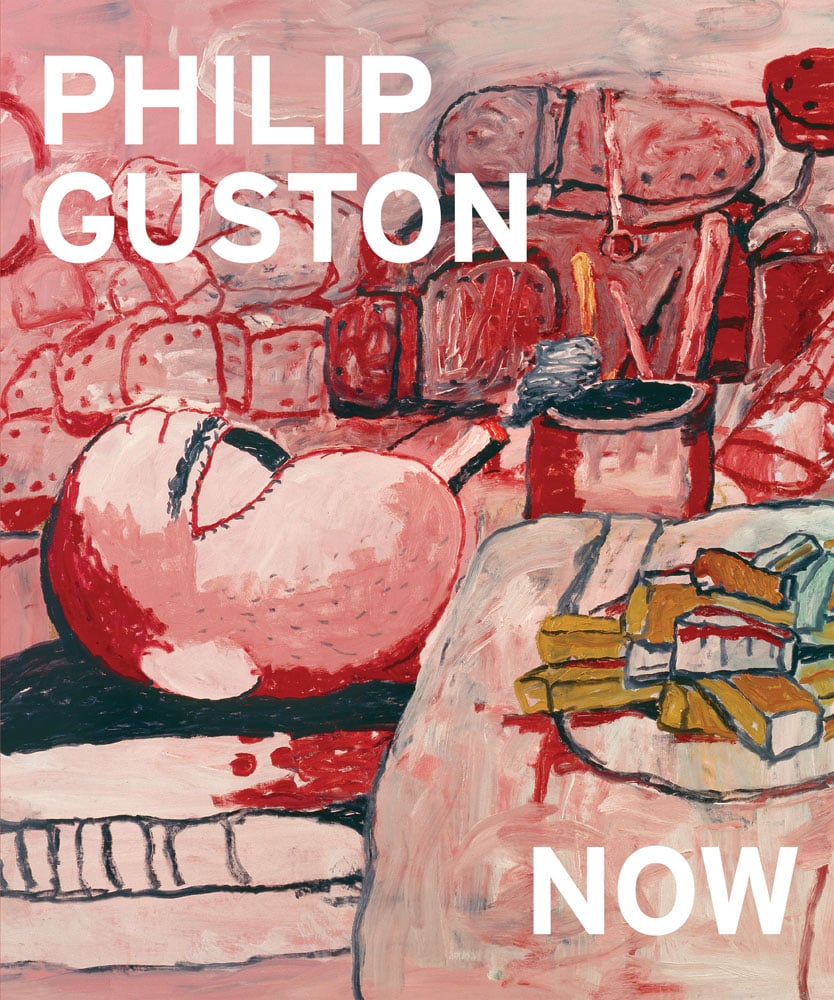

Sharon Helgason Gallagher, Philip Guston: Now. Courtesy of D.A.P. Art Books.

In September, four major museums—the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Tate Modern in London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—announced that they were delaying a major touring retrospective of the work of Philip Guston until 2024. The museums said they were putting off the show “until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

The images at the center of the debate were 25 drawings and paintings that evoke the Ku Klux Klan. Those outraged by the delay included Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, as well as 100 artists, writers, and scholars who wrote an open letter admonishing the museums for the decision. The institutions held fast to their commitment to rework the exhibition—but pledged to move the opening date up, to 2022.

Will Fallout From the Jeffrey Epstein Scandal Ever Stop?

Leon Black. Photo: © 2014 Patrick McMullan Company, Inc.

Fallout from the scandal surrounding the late convicted sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein continued to slip over into the art world in 2020.

The New York Academy of Art was thrown into turmoil after alumna Maria Farmer, an alleged victim of Epstein, accused the school of enabling the late sex offender’s abuse. In response, the academy hired a law firm to investigate Farmer’s claims. But instead of closing the book on the issue, aspects of the investigation were characterized by students and alumni as victim-blaming and biased. Four board members, including actress Naomi Watts, resigned from their roles. The school, for its part, apologized to Farmer and outlined steps to address the issues raised in the investigation.

Meanwhile, billionaire collector and MoMA board chair Leon Black has been under fire for his business ties with Epstein and the roughly $50 million he funneled to the financier over the years. The US Virgin Islands subpoenaed Black—as well as Sotheby’s and Christie’s—in connection with the Epstein case. (A spokesperson for Leon Black’s family foundation previously disputed reports that Epstein remained involved with the organization for four years after his 2008 conviction, noting that his presence on tax forms through 2012 was due to a “recording error.”)

Was a Museum Right or Wrong to Cancel an Exhibition Containing Images of Police Violence?

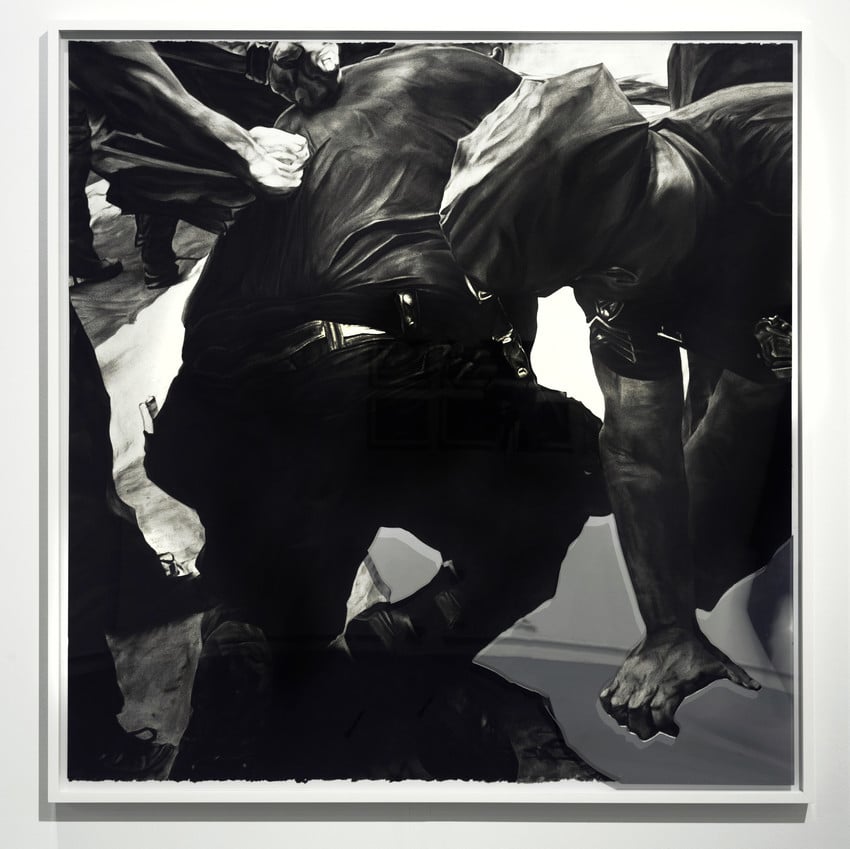

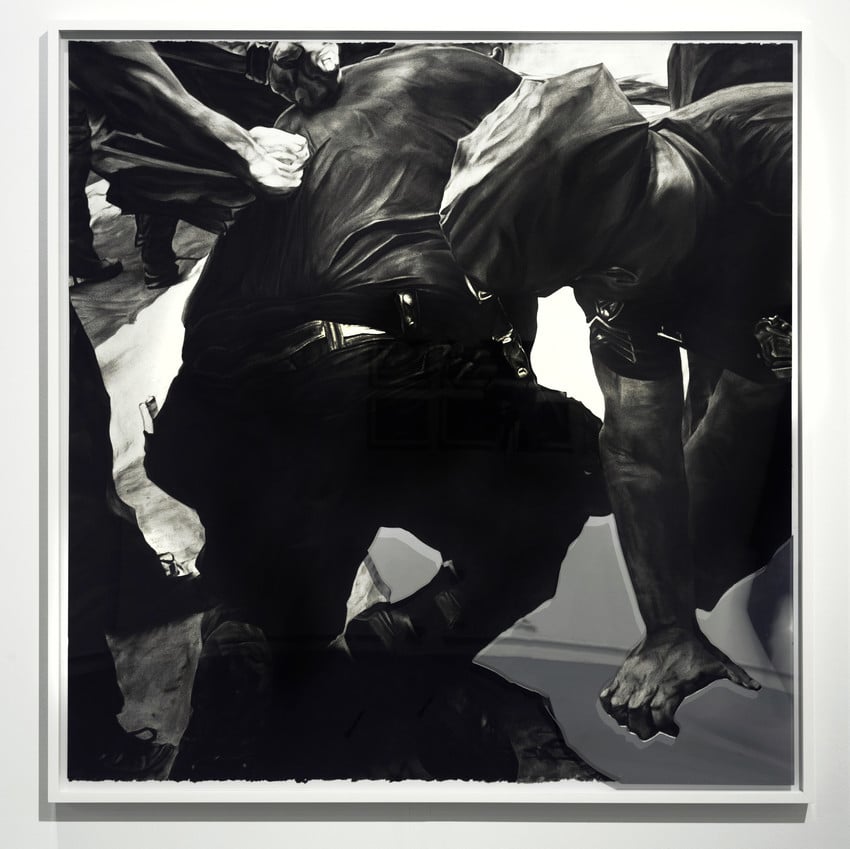

Shaun Leonardo, Freddy Pereira (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Some controversies become more complicated and more gray the deeper you look—and this was one of those. In March, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland quietly cancelled an exhibition of drawings by the artist Shaun Leonardo depicting scenes of police officers killing African American and Latino men. The museum said it had done so in response to feedback from the community, including local activists Amanda King and Samaria Rice (the mother of Cleveland native Tamir Rice). After Leonardo countered that he had not been given the chance to respond to their objections, the museum apologized; its director stepped down not long after. Rice—who, along with King, maintained the museum had made the right decision all along—issued a cease and desist to Leonardo asking him to stop using images of her son in his work. The series in question resurfaced in a show at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art this fall without incident—and without the work depicting Rice. The entire saga was a powerful illustration of the fact that there is still a lack of consensus about best practices in dealing with such difficult material.

Were American Museums Right to Make Layoffs—or Taking the Easy Way Out?

Visitors look at the frescos and the Pergamon altar in the altar room at Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Photo by Maurizio Gambarini/picture alliance via Getty Images.

The statistics have been bleak. Dozens of US museums laid off thousands of employees in the wake of sweeping shutdowns in March—and a second round of reductions hit the sector in June, after government loan money ran out. In that month alone, 17 institutions laid off more than 1,350 workers, according to analysis by Artnet News. But just as workers began to speak up about toxic work environments this year, so they questioned the wisdom—and legality—of these decisions. The New Museum Union filed charges against its employer with the National Labor Relations Board, arguing that management violated the law when it let members of the bargaining unit go. One longtime curator at the Nelson-Atkins resigned in protest of its layoffs.

Some onlookers, like signatories of a petition assembled by SFMOMA staff, asked why museum executives with “unreasonably large salaries” weren’t taking deeper cuts. (SFMOMA director Neal Benezra “earns more in one month than a full-time frontline staff member earns in an entire year,” that petition stated.) Others asked why board members were not opening their wallets to retain experienced, valued team members—particularly when staff at museums were themselves contributing to mutual aid funds designed to support hard-hit peers.