Art World

Here Are 10 of the Best Artworks We Saw Around the World in 2022

Our editorial staff and contributors highlight some of the most unforgettable artworks they saw this year.

Our editorial staff and contributors highlight some of the most unforgettable artworks they saw this year.

Artnet News

This was not a “normal” year by any stretch of the imagination. And yet, among its tragedies and crises, 2022 was marked by a return to a pattern of art-viewing that was more akin to life before the pandemic. Art fairs, biennials, and exhibitions were able to run their course for the most part, and many people were able to move around the world to visit them. We are grateful for that.

In such trying times, art has a crucial function to spur discussions and help widen our view. Along the lines of this criteria, our editorial staff and contributors each highlight an artwork they saw this year that they will not soon forget.

Marlene Dumas, Magdalena (A Painting Needs a Wall to Object to), 1995. Private collection. Photo by Peter Cox, courtesy of Zeno X Gallery.

Sometimes, it feels like I am wandering the art world chasing a ghost; rarely do I find work that reaches out and really moves me, or sets off a tremor. So, I was delightfully blind-sided by Marlene Dumas’s titanic show at Palazzo Grassi in Venice. It sent me reeling and I was not expecting it. I thought I understood Dumas, having read and edited pieces about her, and seen her work here and there, quite consistently. “Open End” (what a title) proved to me that intense investigations of the human spirit, when done with honest curiosity and care, are transcendent and timeless. It also reminded me that painting is a powerful vessel for this kind of labor.

On view in this monographic show are around 100 works, mostly paintings, by the South African artist, that capture a breadth of human emotions: love, loss, idolatry, loneliness, tenderness, and rage. In many works, these feelings are stirred up together. Magdalena (A Painting Needs a Wall to Object to) is one such piece: a dark figure gazes over her shoulder defiantly, shamefully. The painting seems to be made with affection and apprehension. An understanding of the moment it captures is impossible, which makes it all the more enrapturing. I could try to explain it further, but I think best to just quote Dumas (she is also prolific with words), speaking about the pursuit of painting in 1986: “The artwork itself is not dangerous. Murderous thoughts are not the same as actually committing a murder. I paint because I am scared. Give me artworks that vibrate with a sense of their own futility … Because the danger remains the same and the danger never seems to go away. I’ll leave you in mid-air. Without saying goodbye.”

Leandro Erlich, Swimming Pool (1999) at Pérez Art Museum Miami. Photo courtesy of Katya Kazakina.

“How is this even possible?” I gasped at a photograph of a man walking calmly on the bottom of a swimming pool, its water rippling and glimmering in the sun above. There was no visible distress, no swimming motions—just a figure strolling around and waving at the camera. It looked magical. I was instantly hooked, and rushed to the museum as soon as I could get away from the convention center, where I was covering Art Basel Miami Beach. Erlich, who lives in Buenos Aires, is a master of illusion, created painstakingly and poetically to question reality. I will not spoil the experience for those who may see the installation, but let me just say that I loved the transporting, somewhat dizzying experience. Make sure to go upstairs for the rest of Erlich’s first comprehensive career survey in North America. It’s full of surprises and humor. The most mundane objects and settings—a classroom, an elevator, a dryer—are recreated to the last small detail only to defy the laws of nature and elicit wonder, fear, confusion, and joy.

Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt, Maskenfiguren (Mask figures), 1924 at “Biennale Arte 2022: The Milk of Dreams” in “Time capsule V: Seduction of the Cyborg” at the Arsenale, Venice Biennale. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Walking through Cecilia Alemani’s international exhibition at the Venice Biennale, I almost felt as though it had been curated with me in mind. Around each and every bend was the work of another amazing woman artist—both familiar faces and new (at least to me) discoveries—highlighting female contributions not only to the contemporary art landscape, but to the annals of art history.

Perfectly highlighting this unique approach was the work of Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt, a German husband and wife duo who, from 1919 to 1924, created elaborate and fantastical costumes in which to perform their Expressionist dances. These were characterized by intense movements such as “creeping, stamping, squatting, crouching, kneeling, arching, striding, lunging, and leaping in mostly diagonal-spiralling patterns,” according to the 1997 book Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935.

The couple’s routines, performed under the moniker Die Maskentänzer (“The Mask Dancers”), obviously demanded equally bizarre outfits. Often animalistic in nature, the science fiction-flavored costumes were works of art in their own right, completely obscuring the human form.

Unmentioned in the biennale wall text, however, was the reason Schulz and Holdt’s partnership was so short-lived. Unable to make a living from their art and facing financial ruin, the couple died in a murder-suicide, with Schulz shooting her husband before turning the gun on herself.

Miraculously, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts) had the foresight to save the couple’s things in the wake of the tragedy. The costumes, painstakingly crafted from a wide range of materials including wood, wire, burlap, cardboard, papier-mâché, plaster, leather, and quilted fabric, are part of the institution’s collection to this day, having been rediscovered in museum storage in 1988.

Because the originals are too fragile to travel, the biennale featured contemporary recreations from 2005 and 2006. A dramatic presence in the Arsenale galleries, they were paired with black and white photographs of Schulz and Holdt modeling their outrageous looks, shot by Minya Diéz-Dührkoop just a few months before the artists’ deaths.

Even without knowing the sad backstory, the pieces feel misunderstood—unsettling and strange, both joyfully cartoonish and vaguely threatening. Though Schulz developed a graphic notation to record their choreography for posterity, viewers don’t need to experience the dance element to see that the couple’s sculptural garments alone were clearly ahead of their time. Seeing the work was a reminder of the risks that artists take when they work outside the mainstream, eschewing prevailing trends to follow their own artistic vision—no matter the cost.

Installation view of “Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept,” including Jacky Connolly’s Descent Into Hell (2022). Photo by Ron Amstutz, courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Over the past half-decade or so, I’ve become more and more convinced that the artworks best able to capture the tensions of our increasingly tech-dominated lives are artworks that turn software back on itself and, to some extent, back on us. Nothing I saw this year executed this move more memorably than Descent Into Hell, the multi-channel video installation that Jacky Connolly largely built from a hacked version of 2013 gaming phenomenon Grand Theft Auto V.

The video game took the theme of early 21st century Los Angeles disintegrating into lawlessness and turned it into a series of high-octane missions rewarding anti-heroics, if not outright villainy. Connolly short-circuits this dynamic by creating a dreamlike 30-minute CGI narrative spliced together from atmospheric elements surrounding the game’s central drama. A black sedan turning its headlights onto a lone woman wandering in the mountains, a mother and child cowering in a dank supply room, a hillside cabin set aflame—by bringing these background moments to the forefront and eliminating everything else, the artist transforms a punk riot of active gameplay into a slow-burn, quasi-Lynchian nightmare we can only watch unfold. The deepfake-enabled ending punctuates the prompt that Connolly’s work has left me thinking about ever since: Now that our digital selves are as important (and as vulnerable) as our physical selves in a society fraying further every day, who exactly are we to each other?

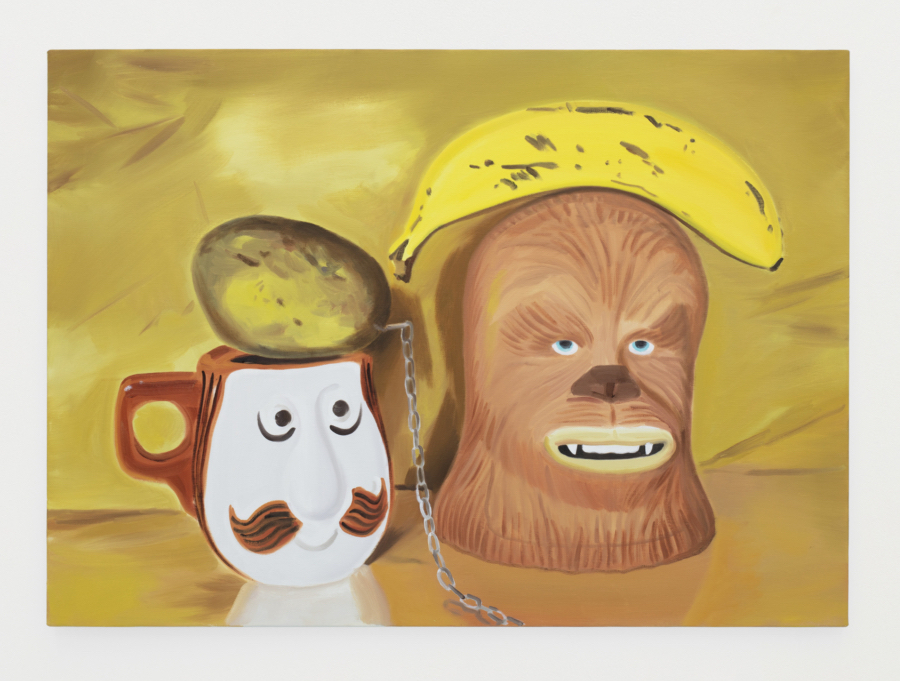

Ulala Imai, Strangers (2021). Image courtesy the artist and Karma Gallery.

Considering how often I stopped by, the team over at Karma must have thought I had set up a tent outside of their East Village gallery through the run of Ulala Imai’s solo show “The Scene.” Imai’s brushy, humor-filled still-lifes feel lighthearted, melancholic, and wistful all at once—the toys she arranges anthropomorphically both delight and pull at the child within you. Teddy bears in patterned robes stand triumphantly with a Chewbacca toy in a field of flowers, suggesting that perhaps the trio had just completed a laborious quest. A series of paintings titled Lovers show Charlie Brown and Lucy in various phases of young romance. Elsewhere, Snoopy reclines under an umbrella of pink and green leaves in his lifeguard’s uniform.

My favorite painting on view was of a vision of moonlight through tall pine trees, presumably painted from the perspective of one of the teddy bears she poses on the forest floor. The moonlight she paints captures the pall of a romanticized childhood, gazed upon by a proxy for childlike innocence.

Two film strips from Carolee Schneeman, Fuses, (1964–67). 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P.P.O.W, New York and © Carolee Schneemann Foundation / ARS, New York and DACS, London 2022.

This historic film work stood out within the pioneering feminist artist’s long-awaited 60-year career retrospective—criminally her first in the U.K. A self-shot video of Schneemann and her partner, the composer and pianist James Tenney, having sex, Fuses is an erotic work through which Schneemann hoped to capture a sense of reciprocal sexual pleasure, reclaiming the male gaze so prevalent in conventional pornography.

Made over a period of three years on a wind-up Bolex camera which could only capture around 30 seconds of footage at a time, the film offers multiple perspectives—the camera is passed back and forth between Schneemann and Tenney, or, at times, the viewer is offered a third-person perspective, sat on a chair, hanging from a lamp, or—in keeping with Schneemann’s provocative sense of humor—taking the low-angled perspective of her beloved cat, Kitch. The erotic scenes are collaged with footage of their house in New Paltz and placid shots of the surrounding pastoral landscape, and Schneemann later purposely damaged the celluloid film by baking it, burning it, dipping it in acid, and leaving it outside to weather the elements.

The result is a battered collage in which male and female body parts fuse into one another, and explicit moments dissolve into fuzzy indistinguishable blizzards of ecstasy. I watched it while sat in the dark next to my fiancé, and while we disagreed on some of Schneemann’s works—and this was certainly not the most controversial work in the exhibition—we agreed that, anyway you slice it, Schneemann’s efforts to convey unconscious and fluid bodily sensations, or “the orgasmic dissolve unseen,” was hot.

Nari Ward, Amazing Grace (1993) at the Nicola Trussardi Foundation. Photo by Marco de Scalzi courtesy of the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi.

Nari Ward’s iconic work Amazing Grace is a chilling installation that, for years, I felt like I’ve known—experienced, even—simply based on images and texts. I was aware it was created with hundreds of abandoned baby strollers the artist had found around Harlem in the early 1990s, in the midst of the AIDS and crack epidemics, and I knew that it spoke of the devastation of entire communities. But moving through the installation in person, on its uneven paths formed by flattened firehoses, it became clear that the work’s unnerving physicality demands the viewer’s moving body, and its layers of references only grow thicker with time.

Installed inside a fascist-era public swimming pool at the end of the summer season this year, as part of Ward’s solo exhibition “Gilded Darkness” curated by Massimiliano Gioni, Amazing Grace was opened up to new, heart-rending interpretations: families torn apart by another drug epidemic in the U.S., anti-immigration populism, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But it also evokes the human cost of overturning of Roe v. Wade, and—in the context of the exhibition’s location—the return to power of ideologies that see women’s primary function as domestic and reproductive. Not many artworks can leap through time and space with so much integrity.

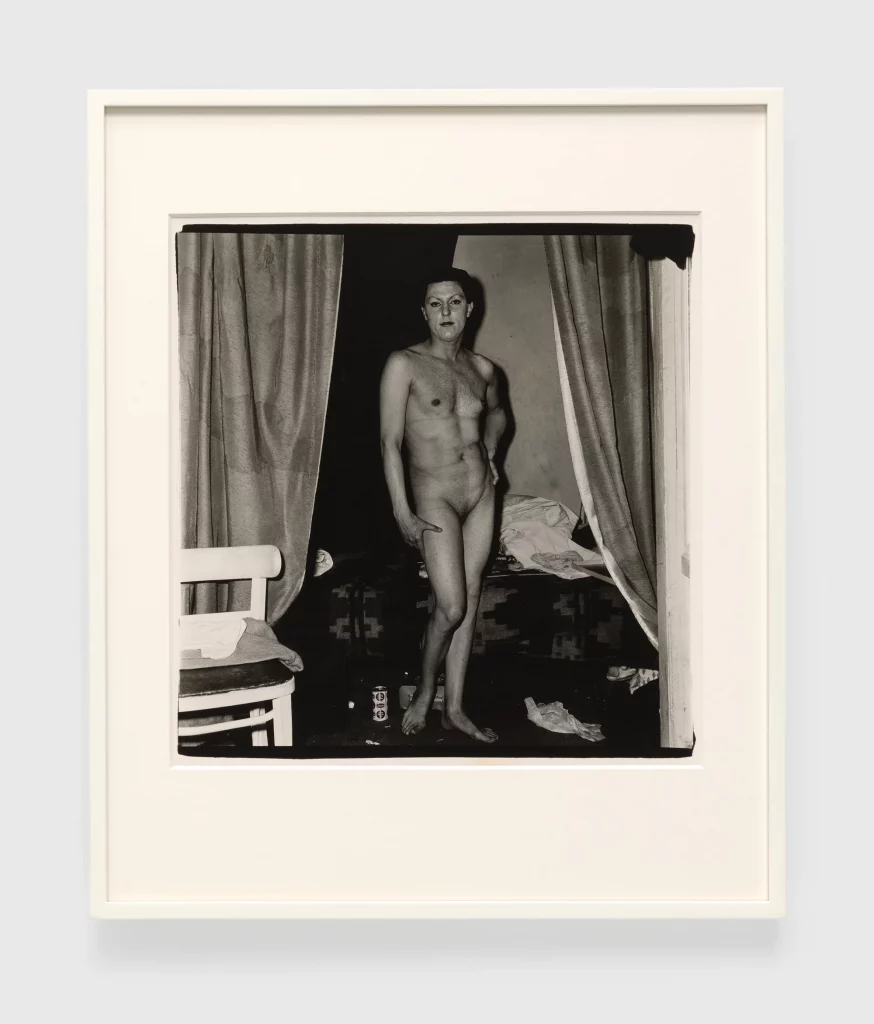

Diane Arbus, A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. (1968). Photo ©the Estate of Diane Arbus.

Maybe it’s a copout to call a 54-year-old photograph by one of the medium’s signature practitioners the “best art” I saw in 2022. The picture wasn’t even necessarily my favorite in the exhibition, David Zwirner and Fraenkel Gallery’s exacting re-creation of Diane Arbus’s infamous 1972 MoMA retrospective. But the galleries’ show, called “Cataclysm,” was the defining art experience—and more than any other included photograph, A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. crystallized what I loved about it.

Today, as during her lifetime, Arbus’s empathic portraits inhibit passive viewing. “What’s captured in [her] pictures is not a ‘decisive moment’ but a conditional set of relationships—a kind of social contract to which we, as onlookers, are made party,” I wrote when the show opened in September. That’s a big idea, but you don’t need to read a thesis on the ethics of portraiture to understand it when looking at A naked man being a woman. To engage with that photograph—and many others in “Cataclysm”—is to engage with what it means to take a photograph of another human. (As good as I thought the show was, the concomitant book of historical criticism about Arbus’s work that Zwirner and Fraenkel published this fall is even better.)

Rinko Kawauchi, installation view of photography series M/E, at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery. Photo by Vivienne Chow.

Picking a favorite work out of Rinko Kawauchi’s solo exhibition “M/E ─ On this sphere Endlessly interlinking” at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery was a challenge. Named after a recent series called M/E, which stands for “mother” and “earth” (it can also be read as “mother earth” and “me”), the show is the Japanese photographer’s first major showcase in her home country in six years. Featuring a total of 180 recent works and images from her archives, this show, beautifully designed by architect Hideyuki Nakayama, guides the audience to see our world, and the relationship between human life and nature, through the lens of Kawauchi. All the works were weaved together into a visual poem of serene images; whether photographs or videos, each work was layered with the artist’s sharp observation and some brutal truth about human lives and our environment.

While the title series is stunning, and there was no lack of mesmerizing photography and video installations in the gallery, my most memorable work was a loop of short video titled Halo. A snippet from a series by the same name created in 2017, this short loop depicted a man beating molten steel against the wall, and the repeated action turned the burning steel into flying sparks, creating a picture of fireworks. Captured at a festival in China, it was lyrical while at the same time ferocious. There was beauty, dangerous manual labor, and the brutal transformation of materials coexisting. But since the video work was so tiny and tucked in the bottom corner of the wall, the work was often overlooked by exhibition-goers. It might have been a deliberate effort from the artist and the exhibition designer, but, regardless of what the story behind it was, Halo was a kind of image that lingered in one’s mind—if you were able to see it.

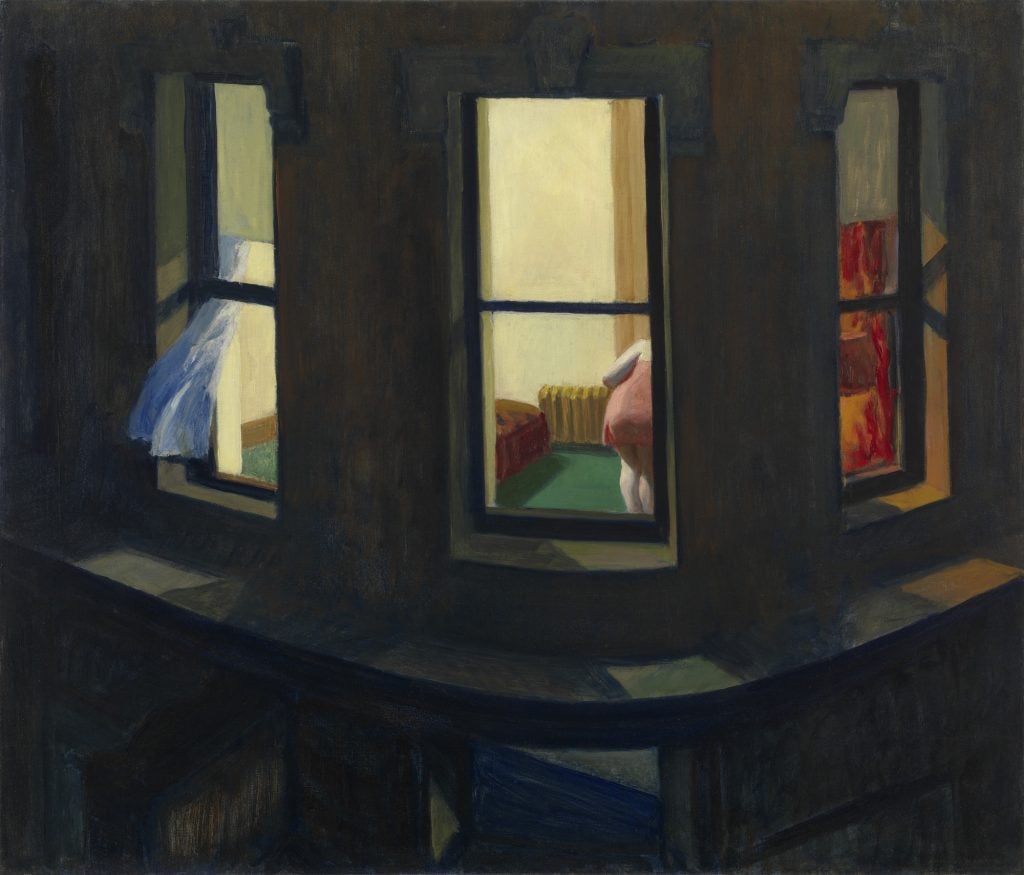

Edward Hopper, Night Windows (1928). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

This work was perhaps one of my all-time favorites in the excellent Whitney Museum show that examines Edward Hopper’s lifelong love affair with New York. The painting depicts a view from the historic elevated train lines that used to run through the city. We get a glimpse of an illuminated room, further highlighted against the darkness of night outside. Just a sliver of a woman’s back is visible as she bends slightly in a seemingly private moment—is she getting changed or slipping into pyjamas? A section of white curtain floats out through an open window suggests a gentle wafting breeze. “The elevated train brought public transport into the private sphere, transforming domestic spaces into theatres for curious riders,” according to the wall text. It’s quintessential Hopper at his best.

More Trending Stories:

The Art World Is Actually Not Very Creative About What It Values. What Would It Take to Change That?

Introducing the 2022 Burns Halperin Report

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now