Reviews

Two Thumbs Way, Way Down: Here Are 6 of the Worst Artworks We Saw Around the World in 2022

Artnet News

Who says criticism is dead? Sometimes, despite an artist’s best intentions, an artwork misses the mark—at least according to some opinions. Art is delightfully subjective, and we are sure that many people hold dear some of the art our editorial staff found, well, less than perfect.

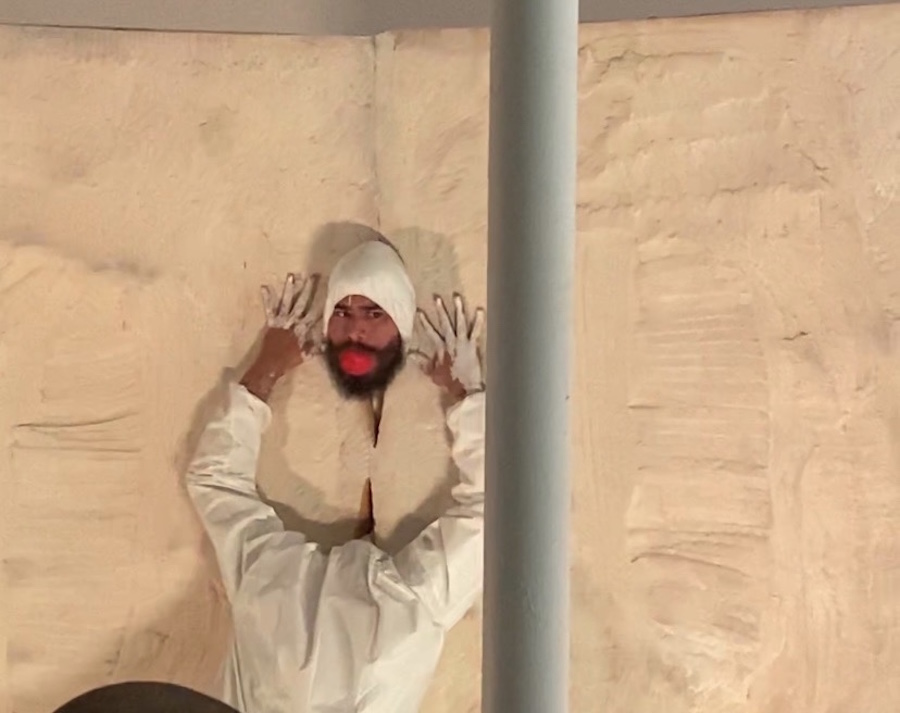

A scene from the NADA Miami performance Boring White Wall by Poncili Creación. Photo by Eileen Kinsella

Okay, maybe it wasn’t the “worst” of the year, but the live performance I stumbled into at NADA Miami a few weeks ago, after a day of viewing great art, was certainly among the most jolting and bizarre. It started with a performer in a white hazmat suit entering the room with a rake, frantically swiping the floor, reaching under people’s chairs, and randomly sniffing startled audience members.

After Poncili Creación’s performer made his way to the white wall—the title of the piece which was a standing foam structure at the front of the room—he proceeded to let out wild screams while alternately hiding behind the wall, attacking it, tearing holes in it, and, eventually, ripping it apart in two with the help of an identically dressed partner performer.

At times a mannequin, also in a white hazmat suit, was tossed wildly in the air and various bright red sponges and appendages that appeared in mouths and hands flew around, seemingly suggesting bleeding or heartbreak. The whole 40-minute-ish performance was accompanied by an equally dissonant live music score with sporadic drums and keyboards that had me wondering the whole time whether or not there was an actual structure—or if the obviously talented musicians were just making it up as they went along. I felt a measure of relief when many others in the packed audience burst into laughter at some of the antics, a reaction that did not ruffle any of the performers in the slightest.

Uffe Isolotto. “We Walked the Earth.” Pavilion of Denmark, Biennale Arte, 2022. © Ugo Carmeni.

I was bewildered by the Danish pavilion this year. I don’t exactly know what the budget was for this pavilion, but in general I feel keenly aware of how much money is floating around the Scandinavian art world, which makes the task of turning out a flashy pavilion in Venice a lot easier. Well-funded artists, take heed: just because you can, does not mean you should.

The Danish pavilion struck me as an immensely overproduced work without a powerful message—at least, the message was not delivered. I found it unequivocally graphic, which left little room for interpretation. The concept of “We Walked the Earth,” so I read, was to evoke a Danish pastoral scene with a surreal and disturbing twist that speaks to modern society. And so, one view were many bales of hay alongside a lifelike centaur with dead eyes lying on the ground post-birth wearing a Uniqlo t-shirt. Another centaur in fetish wear appeared to be dead by suicide. I guess the hyperrealism was supposed to incite macro-contemplation, but it was so under-edited that I left feeling thoroughly annoyed. The over-offering also brought out the worst of our selfie addled culture, and so it continued to haunt my social media feeds all week.

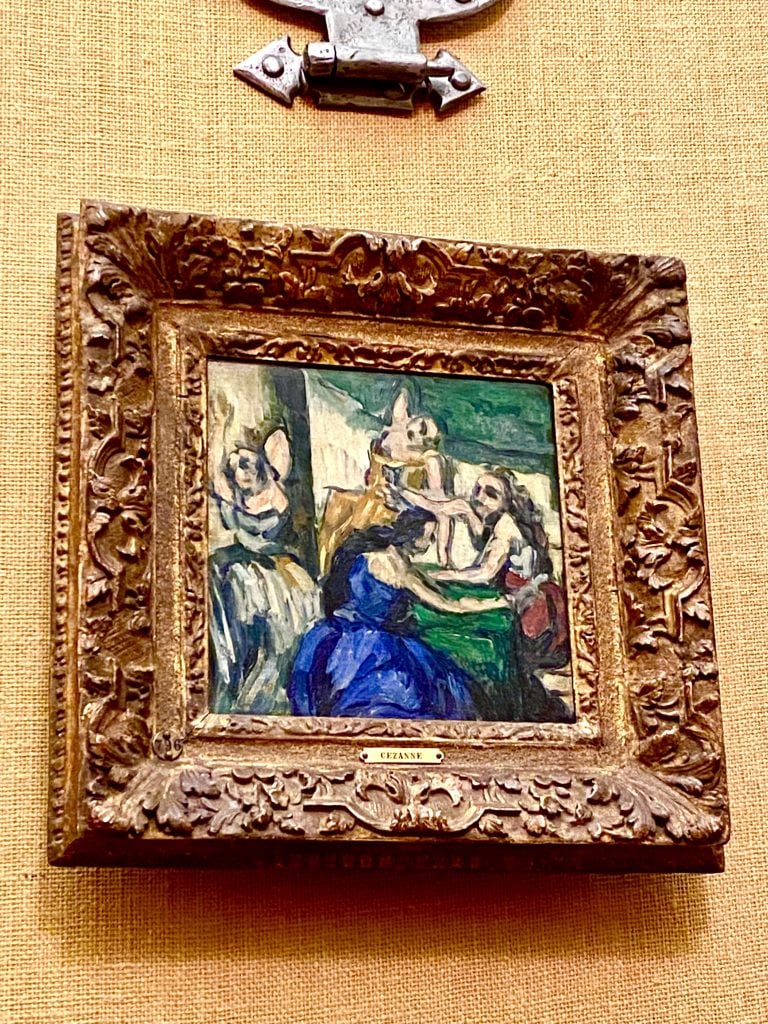

Paul Cézanne, Les Courtisanes (The Courtesans) (ca. 1870–71), installed at the Barnes Collection, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photo by Tim Schneider.

My first visit to the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia this January was one of the most fascinating, disorienting, and memorable art experiences of my year, largely because of the gargantuan variance in quality among the hundreds of works crammed, salon-style, onto every available square inch of wall space. The collection mixes up gems from Hieronymous Bosch, Matisse, and van Gogh (among others) with what looked to me like the laziest castoffs and most catastrophic experiments some of the canonical Modernists must have ever produced.

A reverse standout from the latter category was this blobby, erratic rendering of four courtesans in an illegible mess of a space. (Interior? Exterior? Who can say!) It would be unrecognizable as the work of structural visionary Paul Cézanne if not for the placard unintentionally indicting him at the bottom of the frame. Even at less than seven-by-seven-inches, the canvas made a powerful enough impression to leave me wondering, still, whether Paris’s emerging greats used to quietly compete with each other to see who could saddle the voracious Barnes with their worst dud as part of the bulk purchases that also landed him so many good-to-classic canvases. If so, Cézanne laughed all the way to the victor’s podium.

Damien Hirst at Newport Street Gallery for the grande finale of The Currency. Photo by Naomi Rea.

Time is a precious commodity for a journalist, and especially for an art journalist during Frieze Week in London. Still, I wanted to watch the completion of Hirst’s debut NFT project—a wager that pitted NFTs against physical art—which would see him burn thousands of works on paper potentially worth millions of dollars on behalf of every buyer who had opted to keep one of his NFTs instead. I trekked over to Newport Street Gallery mostly for the anecdote. Hirst is one of few artists whose name extends far enough beyond the art world bubble that it has resonance with my friends and family. And he famously knows how to conduct a spectacle, from his infamous formaldehyde shark to his 2008 market-decimating auction to his phony shipwreck in Venice.

But when Hirst slumped out to take part in the event, it was…really boring? I don’t know if something happened to Hirst—all his previous headline-grabbing stunts happened before my time in the art world—or if this is just what a spectacle looks like in our increasingly digital world, but his utter lack of enthusiasm totally put a damper on the flames. Filmed from multiple angles, it was clear that the main audience was the larger one online than the select audience invited into the room. IRL, it felt kind of like a meet-and-greet with your favorite influencer and seeing the “I’m just here for the paycheck” energy up close.

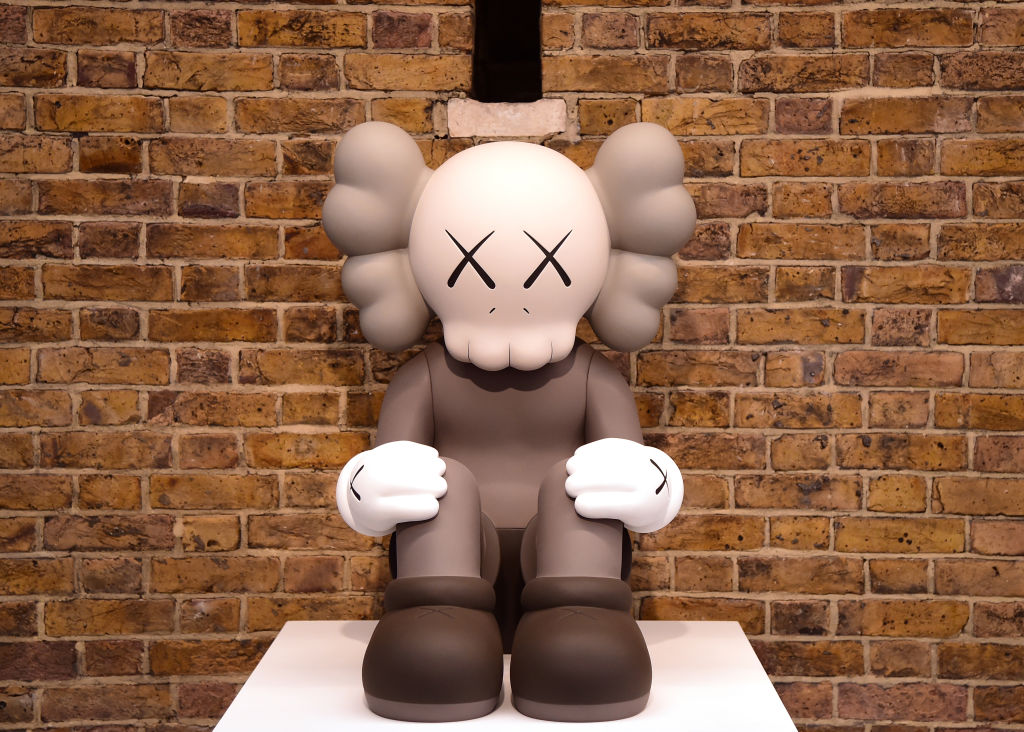

A general view of the “New Fiction” Exhibition showcasing paintings and sculptures by artist and designer KAWS at Serpentine North. Photo: by Eamonn M. McCormack/Getty Images.

I wanted so much to believe that KAWS’s art is interesting. The first-time collaboration between the respectable Serpentine and the online video game Fortnite seemed also like a partnership that could take art to a new frontier in the digital realm, and make art more accessible to the public. But no matter how much the Fortnite players raved about the experience when it was launched at the beginning of this year, I decided to side with the rest of London’s critics who almost unanimously panned KAW’s show. It was not a particular work—the entire art-viewing experience was a let-down.

The only way to appreciate KAWS (aka Brian Donnelly) is to be his fan, and I have yet to convince myself to become one. Seeing the blend of sculptures and paintings based on the artist’s trademark crossed-eye figure Companion did not help. The A.R. versions of Companion sitting on top of the gallery building in Hyde Park or floating inside the gallery space did not make the show more interesting—there are other A.R. works out there that are far more inventive. And the exhibition in the Fortnite game? I don’t play video games, but from the YouTube videos I saw, I hardly observed any players who managed to have any interaction with other players in the virtual gallery. I thought it would be a virtual space that allowed players from all walks of life to meet and greet but, instead, most of them seemed to wander around alone and aimlessly. This could’ve been a wonderful project but, as Alastair Smart suggested in his review, it was a bit of a “lost KAWS.”

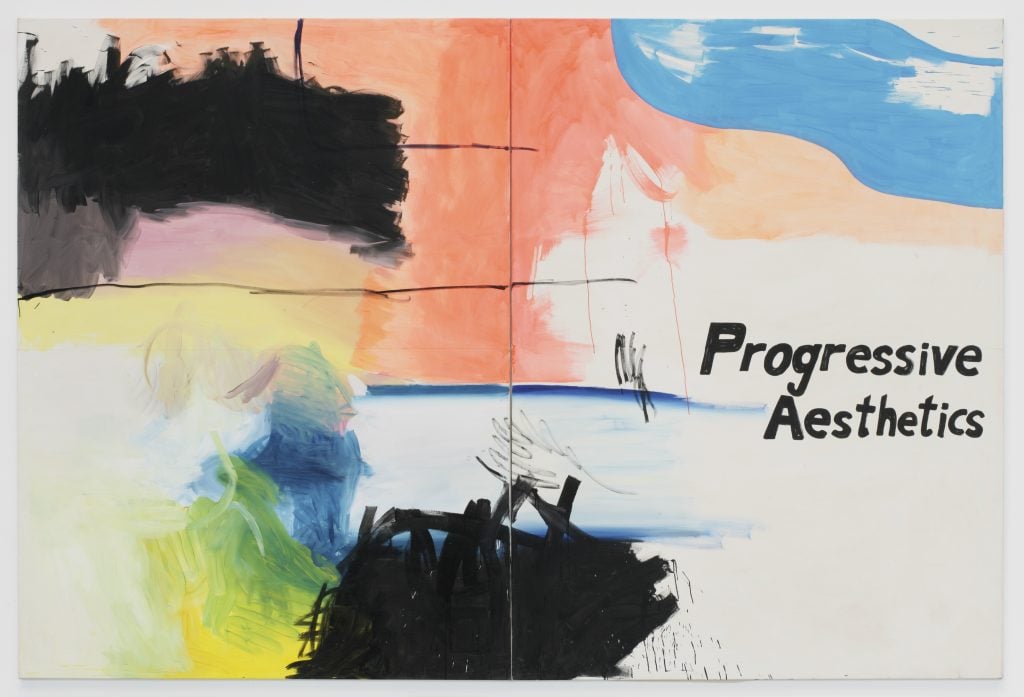

Michel Majerus, Progressive Aesthetics (1997). ©Michel MajerusEstate, 2022, Private collection. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin. Courtesy of neugerriemschneider, Berlin.

I was tempted to call out the life-size bronze of reclining female angel, nude and masturbating, that I saw at Scope Miami Beach, but I will avoid such low-hanging fruit in lieu of a choice that might make me look like the philistine, rather than the artist.

First, I’ll confess that I had never heard about Luxembourgish artist Michel Majerus before the current raft of shows honoring the 20th anniversary of his death. (There are 19 in Germany, and this one in Miami’s Design District, his first solo at a U.S. institution.) Second, I’ll admit that I was completely mystified as to the appeal of his work upon seeing it for the first time.

It was large and colorful, heavy on text, and rife with appropriated imagery from brand logos, cartoons, and other artists—not unlike, I might point out, the kind of pop culture-saturated work typically on offer at Scope. The massive canvases seemed like art in the lobby of a trendy hotel, intended as edgy but in actuality blandly inoffensive. Maybe it’s just me. Maybe Majerus was an artistic genius. (My colleague Taylor Dafoe wrote a great explainer about his career.)

Or maybe this is a “the emperor’s new clothes” deal, where a bunch of rich old guys have invested in Majerus’s work, and orchestrated this wave of renewed attention to drive up the prices on these uber-boring canvases so they can make a killing on the auction block. Feel free to skewer me for my unsophisticated taste if you disagree—but I have a sneaking suspicion I’m not the only one who was underwhelmed when I finally encountered the work of this (IMHO) overrated artist.

More Trending Stories:

The Art World Is Actually Not Very Creative About What It Values. What Would It Take to Change That?

Introducing the 2022 Burns Halperin Report