People

Art Historian Sarah Lewis on Why Black Artists Have Been ‘Over-Exhibited and Under-Theorized’

Lewis has literally changed the curriculum via the Vision & Justice Project.

Lewis has literally changed the curriculum via the Vision & Justice Project.

Folasade Ologundudu

This article is part of a series of conversations with scholars engaged with Black art for Black History Month. See also Folasade Ologundudu’s interviews with Richard J. Powell, Bridget R. Cooks, and Darby English.

***

One cannot consider the present-day field of African American art history without mention of Sarah Lewis. The associate professor of the History of Art and Architecture and African and African-American studies at Harvard University whose groundbreaking Vision & Justice project has become a part of Harvard’s core art history curriculum is a force to be reckoned with.

With her widely watched 2017 TEDX Talk on visual imagery as a change agent for narratives of Black life, Lewis argued that the power of photography can affect our perceptions of justice, reshaping our understanding of society. She has served both on Obama’s National Arts Policy Committee and as a curatorial advisor for Brooklyn’s high-profile Barclays Center.

In correspondence, Lewis shared the intimate family moments that propelled her into the fields of academia and art, the ways in which Black artists combat injustice through their work, and how the field of study—African American art and art history—has changed over the past two decades.

What is your personal story of entering the field? What initially drew you to the fields of art history, architecture, photography, and social justice?

I came into the field because of my grandfather, Shadrach Emmanuel Lee. He was expelled in the 11th grade from a New York City public school for daring to ask why his history textbooks only showed images of white Americans. He wanted to know where the whole world was, and didn’t believe the teacher who said, in that year of 1926, that African Americans in particular had done nothing to merit inclusion. His pride was so wounded after being expelled for daring to ask about this that he never went back to school. But he became a painter, and, a bit like the impulse of a Kerry James Marshall or Kehinde Wiley, if you will, created images where he knew he should have been able to expect to find us.

My name, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, is meant to honor my grandfather. I wish he could see that I’m now teaching and researching the very topics that he was expelled for asking about nearly 100 years ago, focusing on representational justice.

By the time I got to college, I thought I was going to be a painter. I learned to draw and paint at my grandfather’s knee. But I got hooked on the history of the field after a few history of art classes. A proctor in my freshman dorm room sensed my interests and, I’ll never forget it, gave me one of Richard Powell’s fantastic books, Black Art and Culture in the 20th Century (Thames & Hudson, 1997). (Ironically enough, in full disclosure, I joined the board of Thames & Hudson last month). She signed the book, “with great expectations.” At home, my parents had a few books by Deborah Willis out in our living room. The signs were all around.

What would you say the status of Black art history within the discipline of art history today? Is progress being made?

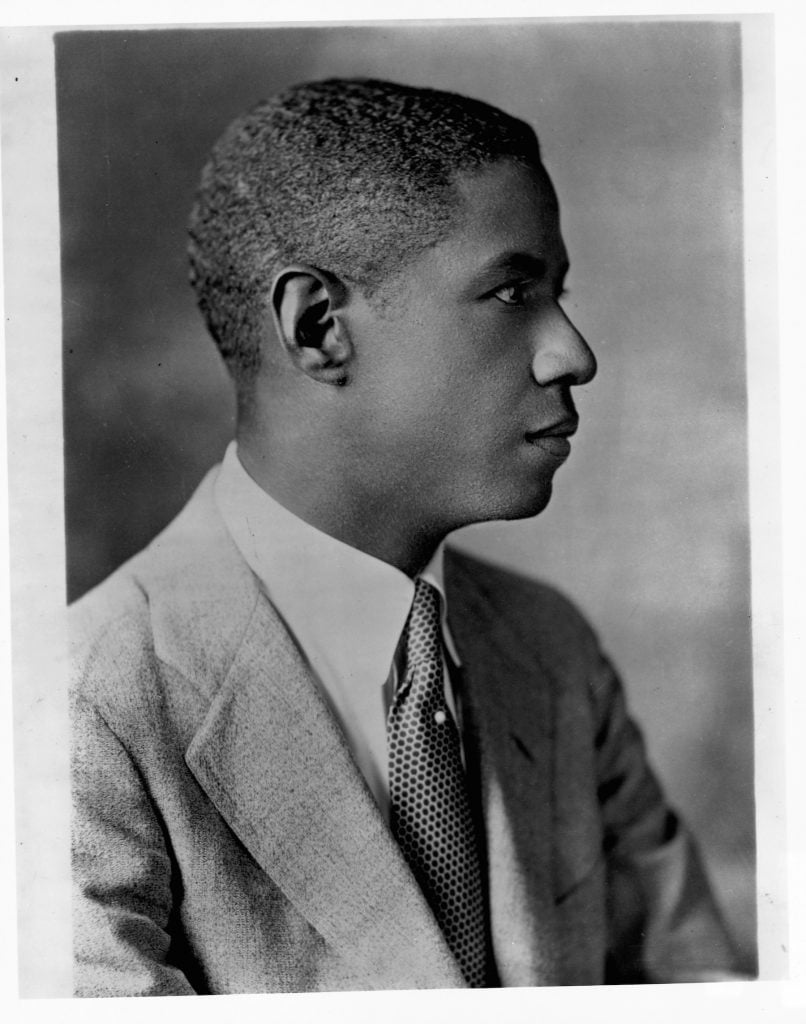

That is a great question and an important one. The status of Black art history—African American, African diasporic or Black Atlantic art history—within the discipline is that it no longer needs a status update—a good thing. It exists. It is established. I am fortunate to be working at a time when that is the case. We salute not only the extraordinary senior art historians working today for that fact, but the legacy and lineage of those who also made this possible—including James Porter, Alain Locke, David Driskell, and so many more.

Art historian James A. Porter. (Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Your first museum job was at the Museum of Modern Art and you’ve worked at the Tate in London. Can you briefly describe these experiences, and some of the biggest observations you made about the institutions with regards to their approach to the stewardship and/or lack thereof of African American art and history?

I’ve been so fortunate with the curatorial opportunities I worked for early on. After a brief internship at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, I worked as a curatorial intern at the Tate Modern in London, working directly with Donna De Salvo before she came to the United States and worked at the Whitney. I was in graduate school then. She was wonderful to learn from; a clear, visual thinker.

After graduating from Oxford University and the Courtauld, I worked at the Museum of Modern Art in two departments—the Department of Painting and Sculpture and then the Department of Photography. I supported Robert Storr on his retrospective of Elizabeth Murray. Working with them both opened my eyes to so much about the politics of the art world.

Installation view of “The Dissolve,” the 2010 SITE Santa Fe Biennial, co-curated by Sarah Elizabeth Lewis and Daniel Belasco. (Photo courtesy SITE Santa Fe.)

I also co-curated the SITE Santa Fe Biennial in 2010 and then became the inaugural curator at the Barclays Center. What shifted my path was when I was asked to research the holdings of African American art in the collection at MoMA and this is what fueled much of my time there. I would stay late, very late, just studying the collection.

At MoMA, I realized that we can get so fixated on the “what” that we forget the “why.” I needed to go to graduate school full time in order to place my study of African American art in a historic context.

In your opinion, how do museums and institutions hold power within the realm of art history? How do they continue to shape our views of what African American art history is as a field of study and a culturally lived experience?

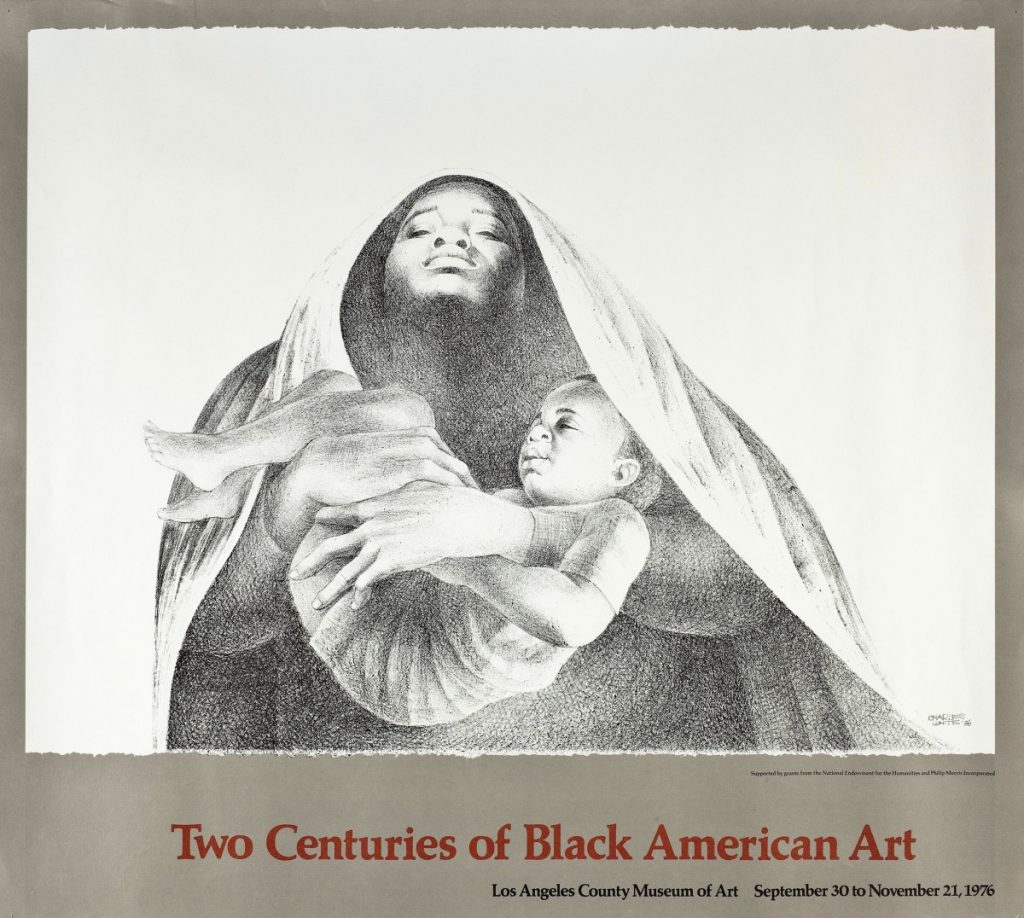

Another important question. Museums are central for establishing and redefining the narratives that shape the history of the field. In fact, much of the field of African American art was forged through arguments made via exhibitions. One good example is David Driskell’s “Two Centuries of Black American Art” at LACMA.

Poster for David Driskall’s “Two Century of Black American Art” at LACMA, featuring Charles White, I Have a Dream (1976).

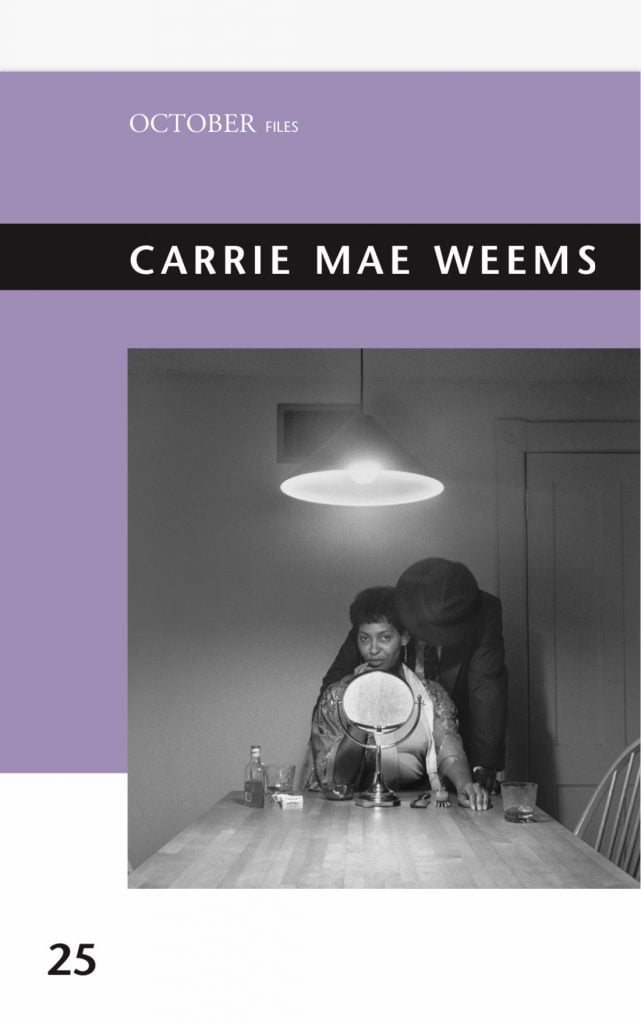

What is interesting about our current moment, however, is that we are seeing, I would argue, power shift not so much away from museums, but becoming shared with the work of scholarship to properly position Black artists within the grand narrative of history. When you study the work of even the most celebrated Black artists—as I noted when finishing the MIT Press October File on Carrie Mae Weems—you often find that their work has been over-exhibited and under-theorized, and this has created an asymmetry between acclaim and the discourse on their work. This has all sorts of consequences for market value, yes, but for me, most importantly, their place within history.

Cover of October Files: Carrie Mae Weems, edited by Sarah Elizabeth Lewis (MIT Press, June 2021).

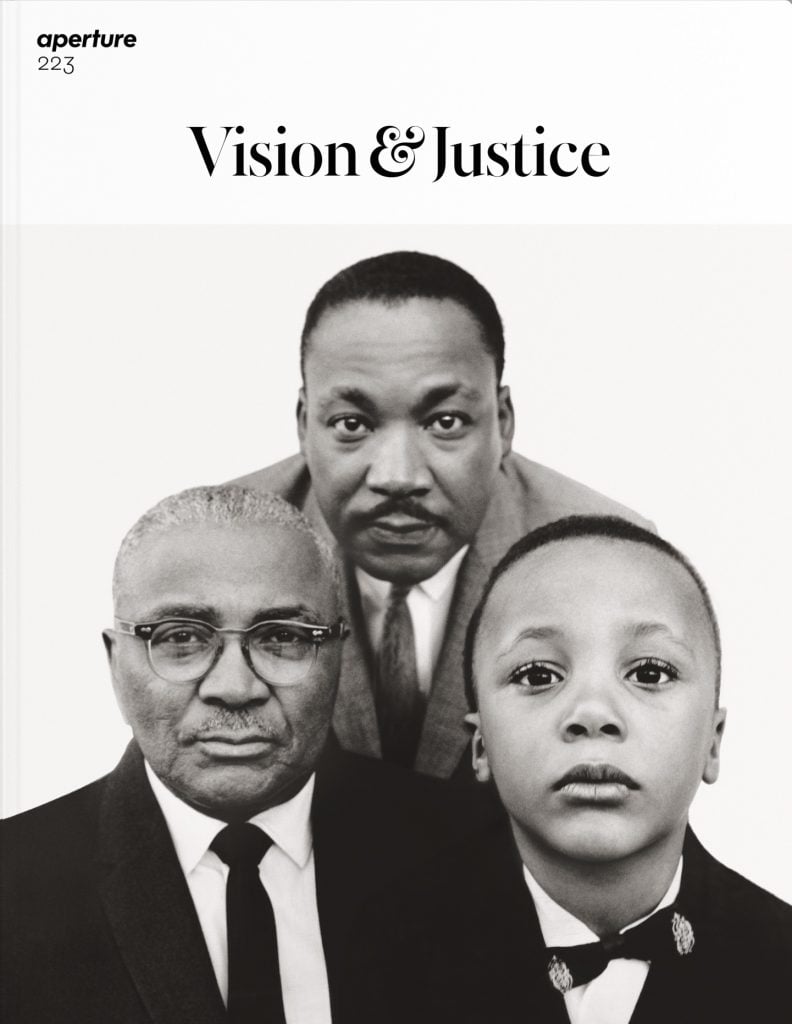

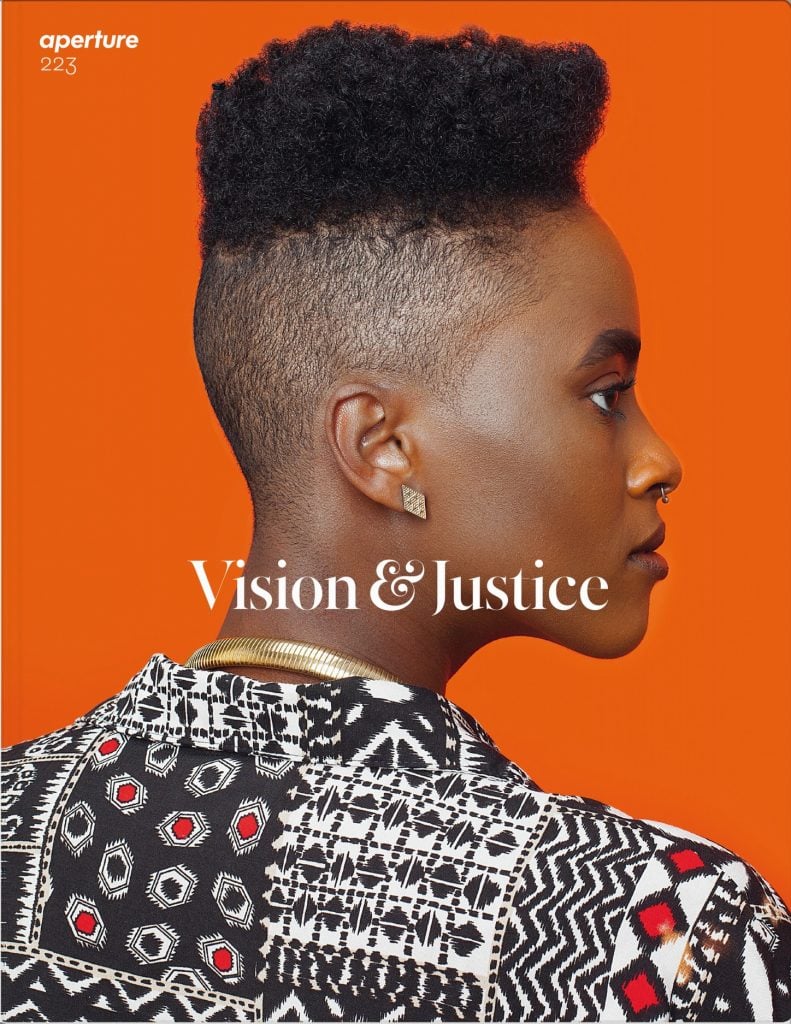

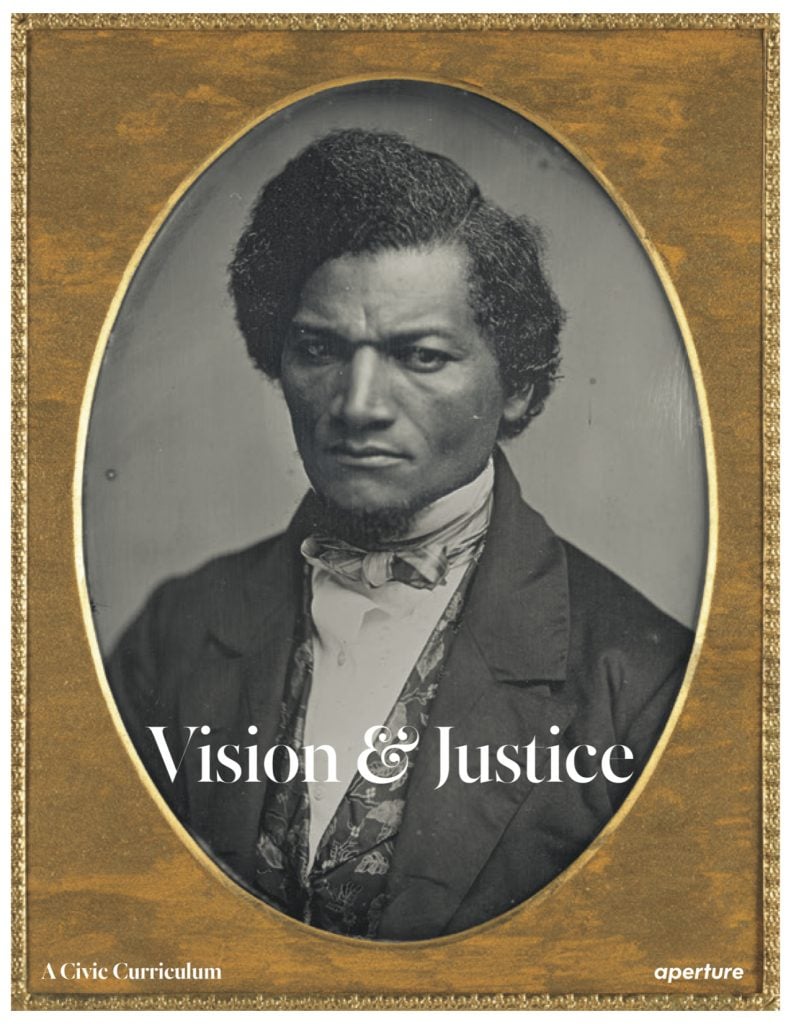

You guest-edited the award-winning “Vision & Justice” issue of Aperture (May 2016) and developed the related “Vision and Justice: The Art of Citizenship” course at Harvard, which has become part of the core curriculum. How will these two important efforts affect change in the study and focus of African American art history?

My hope is that this ongoing Vision & Justice Project supports the investigation of the inextricable connections between art and law in this country, a relationship best studied through an investigation of the history of Black cultural production. Lately, this project has extended into a discussion about what we mean by the figure/ground relationship and opened up a question about Black art teaching us about what we call the ground.

One of two covers of Aperture 223, “Vision and Justice,” featuring Richard Avedon, Martin Luther King, Jr., civil rights leader, with his father, Martin Luther King, Baptist minister, and his son, Martin Luther King III, Atlanta, Georgia (1963).

How are artists, and how is the discipline of art history, responding to the hyper-visuality of racial injustices on American ground? We see that a number of artists including Mark Bradford, Theaster Gates, Amy Sherald, Xaviera Simmons, Hank Willis Thomas, and Kehinde Wiley, and new landmarks such as the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, have initiated a set of what I consider to be “groundwork” aesthetics in the Stand Your Ground Era (see Art Journal, Winter 2020 issue).

By “groundwork,” I mean a set of aesthetic strategies through which the literal and figurative meaning of “ground” is destabilized productively to establish new conditions in the era of Stand Your Ground (SYG) law. SYG laws define the right to self-defense, to claim the ground on which one stands if there is a perception of “reasonable threat.” The law disproportionately affects Black lives today. These artists ask the questions the law often does not: What does it mean not to be able to “stand your ground”?

The groundwork project asks questions of art history itself. Is there methodological room in the discipline of art history to consider what we make of these artistic practices focused on bodies denied this upright position of self-sovereignty and agency? Beyond providing a new framework of analysis via groundwork, engaging with the meaning of the term “ground”—as both reason, fact, but also soil itself—to address the injustices wrought at our feet, I see this work as laying out questions for the discipline of art history and related fields to engage more decisively with the sociopolitical life that informs artistic production in the context of racial contestation.

One of two covers of Aperture 223, “Vision and Justice,” featuring Awol Erizku, Untitled (Forces of Nature #1) (2014).

People are referring to this period as the Black Renaissance: a time of racial uprising, and an increase of African American, and African diaspora artists, curators, and professionals working today. Are there significant moments in history that have brought us here or that are worth reconsidering?

It does feel as if there is a greater visibility paid to Black cultural production, but I’m not sure that I equate this with an increase in activity by Black artists so much as a shift in how the work in the field is acknowledged and celebrated.

In your tenure at Harvard, has the interest from the student body changed? Are you noticing an increase in the interest and participation in the scholarship of African American art?

The student body at Harvard is more inclusive and diverse than many think, more so than when I was a student. I remember my shock on the first day of my Vision & Justice class. I was assigned to a large auditorium, one that holds nearly 300 people. The classroom was full and I had to pause for a while before beginning because I was stunned by what I saw—the sea of Harvard students seemed to have no racial majority. It felt as if the future had rushed in the room.

What does it mean to teach history if whiteness is not centralized in the classroom? That’s the note that I jotted down before I started the lecture that day. I think of it all the time. Yes, it certainly increases not only the interest in scholarship on African American art. It changes our attention to inclusive narratives in the discipline at large.

Cover of Aperture‘s second “Vision & Justice” issue, a free publication released on the occasion of “Vision & Justice: A Convening” with the Vision & Justice Project.

Black Lives Matter has opened up a huge new conversation about representation. What opportunities do you see for the field of art history and Black art historians? Are their pitfalls, too?

I appreciated and so agree with what Richard Powell mentioned in your interview—part of what Black Lives Matter has done has opened up a question around representation. This moment has also made me think a great deal about Paul Taylor who has tied the idea of Black aesthetics to that of “assembly.” I think of it as the operational term that defines the opportunity for Black art historians now—to consider how we will continue not just the constitution of the field, but how we impact the assembly of other fields within the discipline of art history.