Art World

Understanding Why Nobody Made Great Art About the Previous World-Shaking Pandemic + Two Other Illuminating Reads From Around the Web

A weekly round-up of interesting readings from around the art web.

A weekly round-up of interesting readings from around the art web.

Ben Davis

Each week, countless articles, think pieces, columns, op-eds, features, and manifestos are published online—and not a few of them cast new light on the world of art. To help sift through this barrage of content, I pick out a few each week that might inspire some larger discussion.

In the last month there’s been a volley of writing looking for the 1918 Spanish flu’s impact on art. All start from the same enigma: the catastrophic damage wrought by this pandemic of a century ago, juxtaposed with how very little we are left with in terms of images or stories that directly reckon with its horrors.

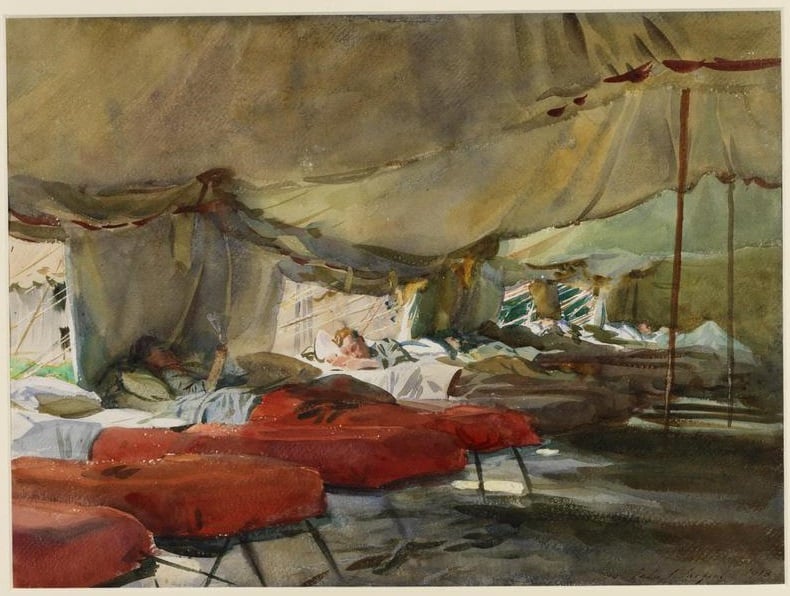

Michael Lobel’s thoughtful Artforum essay tries to find traces of the 1918 pandemic by looking at a pair of works usually read as about the effects of chemical warfare in World War I, both by John Singer Sargent: Gassed (1918-19) and the less famous Interior of a Hospital Tent (1918). He speculates that their depictions of the wounded drew on the contemporaneous experience of the Spanish flu. While working as a war artist, Sargent himself was laid up at a military hospital with influenza, where he recovered alongside both gassed and sick soldiers. In Interior of a Hospital Tent, above, the different-color beds in fact indicate whether the patient was “contagious” or not.

John Singer Sargent, Gassed (1918-1919). Image via Wikipedia Commons.

Art historian Corinna Kirsch, interviewed by Time, argues that you probably have to look for the traces of the pandemic less in specific images, and more in the general tone of the famous art movements that came in its wake. It’s true, for instance, that an obsession with hygiene animated modern architecture. Charles Jencks once remarked on how much the avant-garde architects of the era were inspired by wanting to cleanse the “microbes and streptococci” of the filthy 1910s urban landscape: “The deep metaphor of modernism was that of the operating theater, the hospital, of a place where the difficulties of everyday life would be expunged, would be fumigated out.”

Still, even if you read the art of the ’20s as encoding the Spanish flu as some kind of repressed reference, the question of why art didn’t directly engage with the fallout of such a scarring pandemic seems important—both to understand why we have so few cultural references to anticipate the feeling of living through a pandemic today, and to try to guess at how our own moment might be processed.

The Spanish flu unfolded in tandem with the epochal carnage of the Great War, which crowded it out in historical memory. But, all told, the 1918-’19 influenza pandemic actually killed 10 million more people than World War I, and affected a wider part of the globe, including, as Knox describes in detail, bringing disruption and heartbreak to the US homefront. So you’d think its memory would be more vivid.

Partly, the lack of attention may be due to the well-known news bias towards spectacular, sudden events. The terrorist attacks of September 11, which killed close to 3,000 people, triggered huge reaction, and the museum that commemorates the attack, the 9/11 Memorial Museum in Lower Manhattan, was one of the most-visited in the United States until lockdown. Meanwhile, diarrhea, an easily treatable disease, kills close to 2,200 people every day—and inspires no all-out Global War on Diarrhea, no museum.

Peter Bruegel the Elder, The Triumph of Death (ca. 1562). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The Black Plague brings many, many more images quickly to mind than the Spanish influenza. But these are ciphered through religious imagery, which helped turn a senseless affliction into a Divine Judgement, giving pestilence the face of a Horseman of the Apocalypse, and so fit disease into a meaningful framework. That makes me think that secular societies, cut free from a sense of a divine plan and allegorical thinking by 19th-century science, have a harder time making art about disease. In a world defined only by human events, a plague is both a senseless alien incursion and anti-heroic, sucking away your agency.

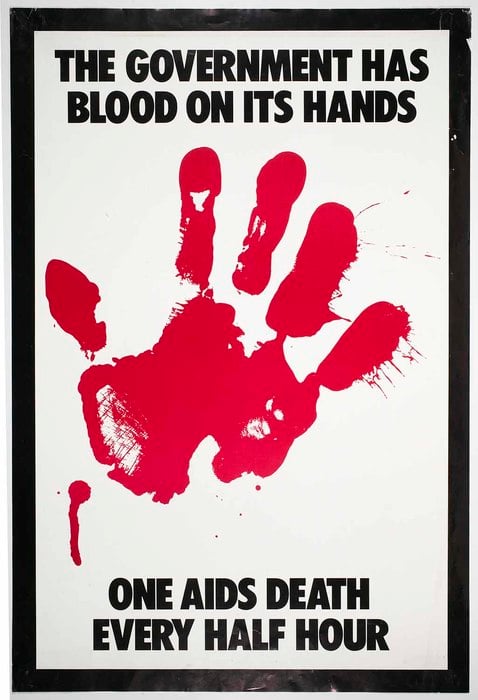

The AIDS pandemic did inspire much memorable and important art. But, thinking about this, I realize that probably the most circulated artworks of the AIDS crisis today are the protest graphics associated with ACT-UP, targeting either government or an indifferent public. These essentially invented a narrative for the plague, rallying a community to fight and naming antagonists. They made the crisis not just a senselessly unfolding public-health event but a condition whose meaning was being shaped by the hostility of powerful people and institutions.

Gran Fury, The Government Has Blood on Its Hands. Image courtesy International Center of Photography.

The Spanish flu was a huge part of the horror experienced by soldiers amid the filthy crush of the front lines of World War I. Yet it doesn’t figure in the memory of the war much, and perhaps that’s for the same reason we don’t think too much about friendly fire as a peril of war: those deaths seem senseless, while soldiers who fall fighting a foe have the entire force of whatever heroic narrative is driving the conflict to make the death meaningful, to turn it into something full of larger social symbolism.

Image of Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin at the Blanton Museum in Austin, which has so far avoided layoffs. Image courtesy Blanton Museum of Art.

Kobel was one of the organizers of the New Museum’s union drive. She was furloughed on April 2 by the New York institution. Here, she surveys the cascading mass layoffs across the museum world, and what they say about the deep inequalities that have festered throughout the system. (As a complement, it’s worth reading Blanton Museum director Simone J. Wicha’s piece this week for the Wall Street Journal about how she avoided making such cruel staff cuts.) In Kobel’s account, I think there’s also the small hope that the mutual-aid networks that have popped up as stopgaps among artists might serve as the germ of a better, alternative art world.

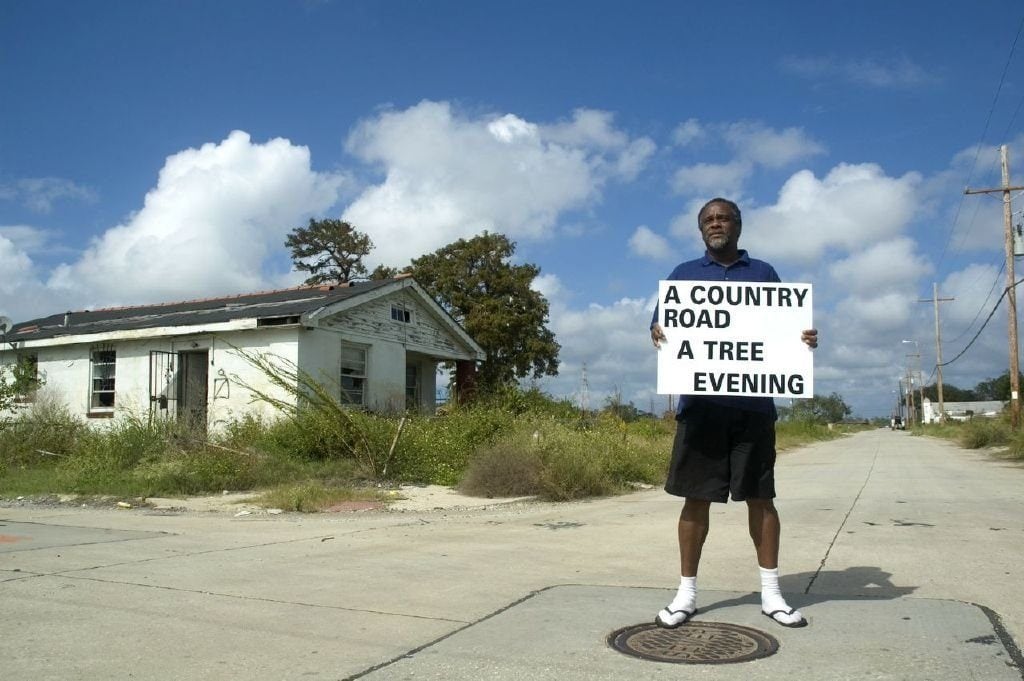

Image from Paul Chan’s Waiting for Godot in New Orleans in 2007. Image courtesy of Creative Time and Greene Naftali, New York.

Paul Chan is one of the sharpest artists around, and this talk he gave to the Hunter College MFA program probably hits me particularly because it resonates with all that stuff I just wrote about pandemic and narrative.

Chan famously staged Waiting for Godot in New Orleans in 2007, with Beckett’s existential play finding new meaning in the immediate post-Katrina environment. Here, he recounts the story of a mother stuck on a rooftop during the flooding of Katrina, her child paralyzed by fear amid the looming threat. She begins telling him a tale. In Chan’s words: “The story was an adventure about two heroes, her and him. The mother recast what was about to engulf them from all sides into an adventure that they—the heroes—had to endure if they were to win the day, and survive.” And through this lens, the child can refocus on reality and fight. Art’s capacities of escapism can also be tools to help escape a reality that is too-present and paralyzing—and so to be able to act on it.

“I came to tell you that what is new in art is a reminder of what is worth renewing in life,” Chan says. “And that what is new in art, and what is worth renewing in life, may depend on cultivating an aesthetic sensibility capable of recasting what troubles us into a plot that is pleasing or interesting enough to warrant our undivided focus and participation.” Beautiful thought.