A shift has taken place in the media in recent years wherein talk of the art market has almost completely supplanted talk of art itself. Art-as-investment, price indices, predictions, statistics, and graphs are the new norm for framing art-world discussions. Large sums of money are reported as trading and, although there is little understanding of how these numbers are achieved or guaranteed, a new breed of buyer has entered the market focused solely on a false perception of liquidity. The result is that we see intense bumps in prices for short periods of time, without any substantive data backing them. The spikes can be so high that a free fall feels inevitable.

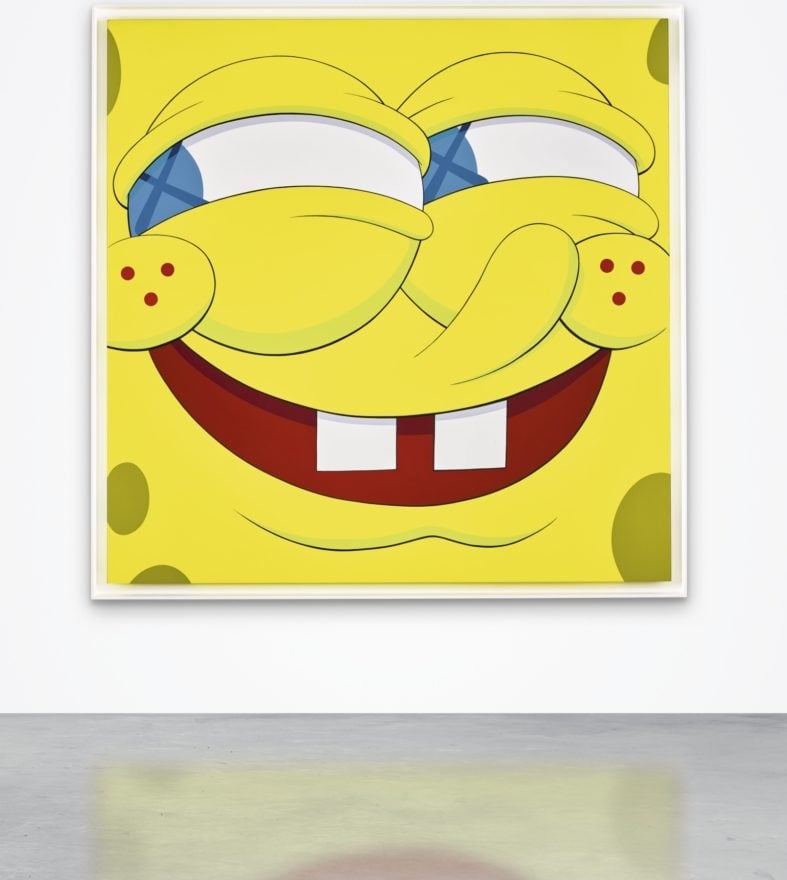

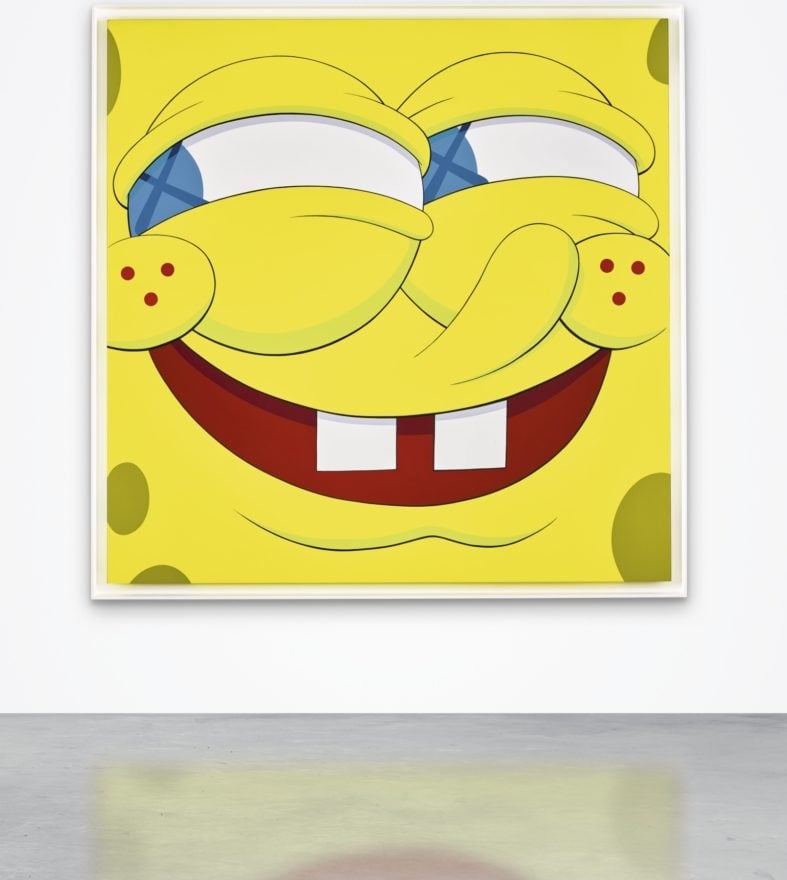

Usually, these short-term moves focus on thin works with little historical relevancy that have mass appeal. At a recent Sotheby’s evening sale, a painting by Kaws depicting SpongeBob outperformed most other lots in the sale, including the only two works by women, Amy Sillman and Pat Steir. When this happens, connoisseurship and emotional-aesthetic engagement take a back seat to quick-and-easy attraction. This trend puts in peril thousands of years of traditional value-making wherein criticality is inextricably linked to growth in the market. SpongeBob is everywhere.

KAWS, Again and Again (2008). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

But what happens when speculation falls on high-quality artists? Is it a good thing? Sometimes thoughtless profiteers with no understanding of art history move away from SpongeBob and actually look at something of import as a short-term play. Recently, artists of color and women have skyrocketed in the market—and I can’t say I’m upset about it.

It’s a little annoying to watch buyers with little interest in the historical plight and struggle of African Americans or in gender inequality suddenly pretend to care and acquire works that they heretofore ignored. But, when the works are of great quality and historical significance, it puts a smile on my face because I believe that some of these artists are so critically important that the inevitable free fall may not happen here. But that doesn’t mean it won’t have long-term ramifications for the art world as we know it.

Phone bidding at Christie’s New York, 2006. Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images.

In recent auctions, benchmarks were made for several female artists. In particular, Joan Mitchell jumped from $11 million to almost $17 million. Njideka Akunyili Crosby made a record price of $3.4 million while Avery Singer made $735,000. These are three very different artists at very different stages in their careers and the only relationship linking them besides achieving auction records is gender (they all identify as women). Joan Mitchell was an Abstract Expressionist whose career spanned decades and includes a long list of renowned museum shows and well-cited exhibition catalogues. Her new record price was long overdue and reflects a healthy jump. Crosby and Singer are both young in age and in the span of their careers. While they do have institutional support, the simple fact that they are even appearing at auction this early in the game indicates that something in the market is off.

It is inspiring to see women publicly achieving prices that were once only attainable by men. But at this stage in their careers, it is potentially harmful. First, the prices attained make it hard for other patrons to resist selling the work. To have bought a work for $50,000 that may now be worth hundreds of thousands, or even millions, is a prospect hard to pass up, even for those who do not need the money.

Avery Singer on Art21. © Art21.

It also sends the wrong message to the people who would stop at nothing to purchase a work on the primary market, only to turn around and resell at an inflated auction price. This sets artists up for issues of trust and fear as discussion of their work revolves solely around the market. This can happen, and has happened to plenty of male artists, but it threatens the staying power of women artists only recently welcomed into the upper echelons of the evening sales. Is this the victory lap for women we were hoping for? Both Crosby and Singer have the critical chops to support their inflated markets; their criticality won’t just disappear. Historically, however, it seems that when artists’ works become market-driven, curators tend to shift their focus, and even the best collectors, who continue to support the output, cannot help but see dollar signs in front of the work.

I don’t think the work of artists this young should be coming to auction at all, nor should there be any resale situation involving prices so high above their primary markets. A healthier situation is a long, slow burn with real context and institutional support. Still, out of my own fear of losing the traditional mechanisms of value making, in which criticality is linked to the market, I prefer that the Crosbys and Singers fly high over the SpongeBobs and the shredded Banksys.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, a 2017 MacArthur Fellow, photographed in her studio in Los Angeles. Photo: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Suddenly I find myself very much against the idea of democratizing the art world if that means selling fractional ownership of Picassos and bolstering street artists whose activism has totally sold out to commercialism. I don’t want to see Crosby or Singer have a free fall and I am hoping that won’t happen. But let’s be clear here: The recent jump in pricing, and even the inclusion of certain women in the evening sales, is not due to any fair and just rationale. It is not because of a healthy growth cycle prioritizing women. Could it be the result of the calculating profit drive of a few men of privilege? I can’t answer that, but I know some in the game.

Lisa Schiff is the founder of Schiff Fine Art, a private art consultancy specializing in modern and contemporary art.