Archaeology & History

The Most Important Archaeological Discoveries of 2021, From Unknown Dead Sea Scrolls to Middle Eastern Cattle Cults

These discoveries have forced us to reevaluate what we think we know about the history of humankind.

These discoveries have forced us to reevaluate what we think we know about the history of humankind.

Sarah Cascone

Every year, we delve back through our coverage to find the most fascinating archaeological discoveries of the year, whether by a complete amateur, or as the result of years of careful study by a team of experts.

As always, archaeology news takes us around the globe and throughout the ages, from the earliest days of human history through to the contemporary era. Here are our picks for the 2021 archaeological stories worth revisiting.

Stonehenge at sunrise in 2015. Photo by Freesally, public domain.

The ancient circle of stone monoliths on the U.K.’s Salisbury Plain is one of history’s most enduring mysteries. But while we may never fully understand this ancient structure, experts are learning more and more about it each year.

Thanks in no small part to the late Robert Phillips, a diamond cutter who made repairs to a fallen stone at the site in 1958, we now know that the massive monoliths are made from a nearly indestructible matrix of interlocking quartz crystals—which is why the monument has stood for millennia. Phillips drilled a three-and-a-half foot core sample during his work, which he was allowed to keep as a souvenir. He returned it in 2019, allowing scientists to conduct valuable testing on the stones, which are now protected under English heritage law and cannot be sampled.

This year also saw archaeologists discover a former stone circle in Wales that closely matches the dimensions of Stonehenge’s inner ring. That suggests that the site’s inner stone circle was originally erected 175 miles away and moved to Salisbury Plain—and carbon dating shows it was built 400 years before Stonehenge proper. If this all seems too unbelievable to be true, just wait: it perfectly matches a Stonehenge legend that Merlin stole the monument and moved it to England.

The lost city discovered by archaeologists near Luxor in Egypt. Photo by Zahi Hawass, courtesy of the Center for Egyptology.

Do the discoveries ever seem to stop in Pompeii? A newly excavated thermopolium, a kind of Roman fast food restaurant, began welcoming visitors this summer. Archaeologists were able to identify the space in part because it was decorated with frescoes featuring some popular ingredients in Pompeii cuisine, such as roosters.

Other Pompeii finds this year included an intact chariot, slaves’ quarters, and evidence of thriving Greek theater scene.

But Pompeii isn’t the only ancient city found nearly intact. In fact, a smaller “mini” Pompeii was found hidden beneath vines in Verona by construction workers. And in Egypt, another wellspring of ancient treasures, 2021 saw what’s being hailed as the nation’s most significant discovery since Howard Carter uncovered King Tut’s golden tomb nearly a century ago: the abandoned city of Luxor.

The city was a royal metropolis outside the city of Thebes built by Tutankhamun’s grandfather, King Amenhotep III. His son, Akhenaten, appears to have abandoned the city when he started a new religion worshipping only the sun god, Aten.

The Discovery of Slaves’ Quarters in Pompeii Provides a Rare Insight Into Life in Roman Times

Rappelling to the Cave of Horrors. Photo by Eitan Klein, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

A Bedouin shepherd found the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947. The earliest known Hebrew biblical texts, they are considered among the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. This year, scholars found new Dead Sea Scroll fragments for the first time in 60 years at a site called the Cave of Horrors.

The site was first excavated in the 1950s, and received its dark name because of what archaeologists first saw—the skeletons of Jewish men, women, and children the Romans killed during the Bar Kokhba Rebellion.

We also learned more about the scrolls thanks to science, when researchers examined the 24-foot-long Great Isiah scroll in microscopic detail. To the naked eye, the writing all looks identical, but AI pattern recognition technology was able to detect undeniable differences, demonstrating it was written by two `different scribes.

This painting of a wild pig in the Leang Tedongnge cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi is thought to be the oldest representational art in the world. Photo by Maxime Aubert.

While archaeologists continue to learn more about some of the world’s most famous historic sites and artifacts, Asia, Africa, and North America have also yielded important discoveries that are helping shift our Eurocentric preconceptions about prehistory and early civilizations.

Archaeologists have never found human remains in Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa, but ancient humans appear to have lived there an astounding two million years ago, which would make it the world’s oldest home. Experts tested different rock laters to determine when humans entering the cave would have tracked in bedrock sediment.

The world’s oldest figurative art, meanwhile, appears to have been found on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, where a cave painting of three wild pigs is now believed to be 45,500 years old. Made with red ochre pigment, the images are shockingly well-preserved. Scientists determined its age by testing a calcite mineral crust that had formed atop the artwork using uranium-series dating.

And then there are, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) mapping tools, which have once again proved a powerful force for archaeological discovery, this time in Cambodia. The laser’s topographical readings of the area surrounding the Angkor Wat complex suggests that what is now jungle was once filled with homes built from organic materials on low-lying mounds. At its height in the 13th century, the region was likely home to nearly one million people, which would mean it was one of the world’s largest pre-modern cities.

Perhaps most intriguingly, in the Americas, our entire accepted theory about human arrival on the hemisphere looks to be in danger of being upturned thanks to human footprints discovered on a dry lake-shore in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park. Radiocarbon on the grass seeds left behind in the tracks determined that the footprints were made between 22,800 and 21,130 years ago—the oldest ever found in North America.

The find is especially significant because historians have long held that humans first made their way to North America from Asia across the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the Ice Age, around 13,500 to 13,000 years ago. But the “Clovis First” theory, the name given to those believed to be the continent’s first settlers, is now in jeopardy of being completely overturned: White Sands’ footprints are the most convincing of a number of potentially pre-Clovis discoveries that could completely change what we know about prehistory.

An illustration of the Suontaka grave now thought to be the final resting place of a nonbinary person from Medieval Finland. Image by Veronika Paschenko.

There were several discoveries this year that prove we still have much to learn about the role of gender roles throughout human history—and how they differ from contemporary norms.

A Finnish grave had long puzzled archaeologists. The person was laid to rest with a warrior’s sword, but also with women’s jewelry. Now, genetic testing on the physical remains, dating to 1050 to 1300 A.D., has revealed that the deceased was a nonbinary person with an extra X chromosome. What makes the discovery all the more intriguing is that the burial suggests that this was a high-status person, and that their embrace of a non-standard gender identity was accepted in society.

Other discoveries this year have identified powerful women throughout the ages. Queen Cynethryth ruled Mercia alongside her husband, with none other than Charlemagne addressing them jointly in a letter. Archaeologists have now found the remains of the 8th-century Anglo-Saxon monastery where she lived out her later years as a royal abbess.

And in Spain, women may have been in leadership positions way back in the Bronze Age. Archaeologists have been excavating burials at a site called La Almoloya that dates to about 2200 to 1550 B.C. The different types of artifacts buried with men compared to those found with women’s remains suggest that while men had military control, it may have been the women, who came of age earlier and wore elaborate silver diadems, who held political power in society.

Three monumental mustatils and a later funerary ‘pendant’ located atop a rocky outcrop on the border of Khaybar and AlUla counties. Photo courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

In December 2019, Canada’s Wanuskewin Heritage Park began reintroducing bison, hunted nearly to extinction over a century ago. This fulfilled a long-held wish of the local Indigenous people, the Wahpeton Dakota, who prophesied the animals would bring good fortune. Eight months later, the park archaeologist realized the bison were taking their dust baths amid 1,000-year-old petroglyphs, including a 550-pound boulder carved to depict bison ribs—called a “ribstone”—as well as other carvings, and a stone knife that may have been used to carve them.

Cattle also made archaeological headlines in Saudi Arabia, where archaeologists dated the ancient monuments known as mustatils to 8,500 to 4,800 years ago. By comparison, Stonehenge and the oldest Egyptian pyramids are 5,000 years old or less. We now know there are over 1,000 mustatils across 77,000 square miles of desert. They range from low rock walls forming long rectangles (and take their name from the Arabic word for the shapes) to more elaborate constructions with pillar, chambers, and interior walls.

And where the does cattle come in? The mustatils may have been built for religious rituals, praying for rainfall to support their cattle farming during droughts, as the region at the time would have been an unrecognizably verdant landscape.

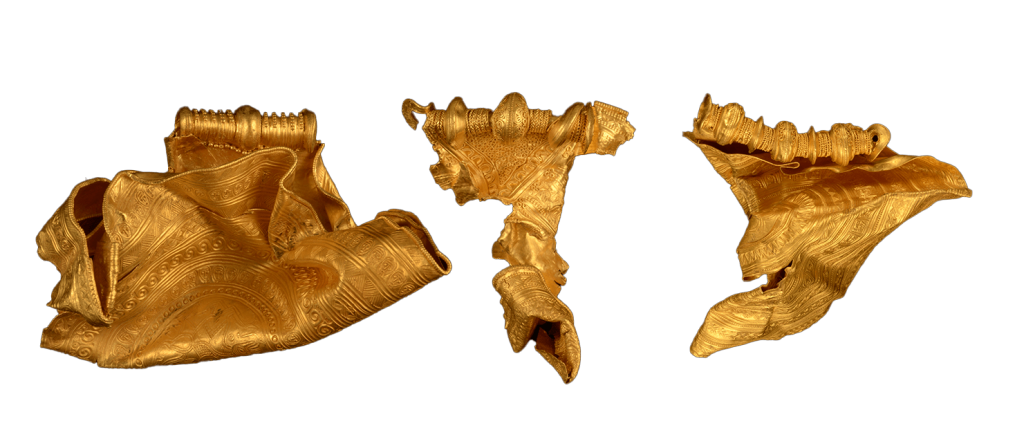

A first-time metal detectorist discovered this golden treasure from the Iron Age in a field near Jelling, Denmark. Photo courtesy of the Vejlemuseerne, Denmark, Conservation Center Vejle.

It turns out that metal detecting is a pretty pandemic-safe hobby, so the world has seen an explosion of very discoveries made by backyard amateurs, like the man in Denmark who found a stunning cache of 6th century gold jewelry his first time using a metal detector. (At first, he was convinced he had dug up the lid of a herring can.)

The U.K. has proven particularly fertile ground, with one woman alone unearthing two separate hoards of Viking treasure on the Isle of Man. The nation’s other finds include a gold and enamel Medieval skull ring in Wales, the largest-ever haul of Anglo-Saxon gold coins, and a tiny gold book from the 15th century.

Can’t get enough? Here are other art-world discoveries we covered this year:

Archaeologists Have Identified the Only Known Example of a Pregnant Mummy

New Archaeological Find in Utah Suggests Humans Have Been Using Tobacco Since the Ice Age

In the Underwater Egyptian City of Thônis-Heracleion, Divers Have Discovered an Ancient Warcraft

Archaeologists Have Unearthed 2,000-Year-Old Mummies With Gold Tongues at an Ancient Temple in Egypt

Archaeologists Have Discovered the Lost Ruins of Maryland’s Earliest Colonial Settlement

Archaeologists Have Discovered a 3,200-Year-Old Mural of a Knife-Wielding Spider God in Peru

Machu Picchu Is Even Older Than Previously Thought, New Radiocarbon Dating Shows

Archaeologists Have Discovered Ancient Bronze Age Homes at Germany’s ‘Stonehenge’